Text-To-Speech With AWS (Part 1)

This two-part series presents three projects that teach you how to use AWS (Amazon Web Services) to transform text between its written and spoken states. The first project will use text-to-speech to turn a blog post or other written content into a spoken .mp3 file to give more options to blind and dyslexic users of your site.

In the next article, we will embark on the return journey, from speech-to-text, and consider the accuracy of these transcriptions by sending various samples through a round-trip translation. To follow these tutorials, you will need an AWS account with billing enabled, though the tutorials will stay well within the constraints of free-tier resources. Examples will focus on using the AWS console, but I will also demonstrate the AWS CLI (Command Line Interface), which requires basic command line knowledge.

Introduction And Motivation

Most of the Internet is text-based. Text is lightweight (1 byte per letter), widely supported, easy to interpret, and has a precedent as old as the Internet as the default medium of online communication. Sending written text predates the Internet: telegraphs carried text over wires hundreds of years ago and physical mail has transmitted writing for centuries. Voice transmission over radio and telephone also predates the Internet, but did not translate to the same foundational medium that text did online. This is in almost all cases a good thing, again, text is lightweight and easy to interpret compared to audio. However, transforming between voice and text can add powerful functionality to and improve the accessibility of a wide variety of applications.

It has always been possible to transform between audio and text, you can read a written speech or transcribe an oral sermon. Indeed, if we think back to the telegram, trained operators transcoded Morse Code messages to words. In each example, it has always been very labor intensive to move from speech to writing or back, even with specialized training and equipment. With a variety of cloud services, we can automate these processes to allow transitioning between mediums in seconds without any human effort, which expands the possible use cases.

The most obvious benefit of implementing appropriate text-to-speech and speech-to-text options is accessibility. A visually impaired or dyslexic user would benefit from a narrated version of an article, while a deaf person could become a member of your podcasting audience by reading a transcript of the show.

Text-To-Speech Project

Say you wanted to add narrated versions of every post to your blog. You could purchase a microphone and invest hours into recording and editing spoken renditions of each post. This would result in a superior listener experience, but if you want most of the benefit for only a couple of minutes and a few pennies per post, consider using AWS instead. If you are the sort of person who regularly updates and revises older or evergreen content, this method also helps you keep the spoken version up to date with minimal effort.

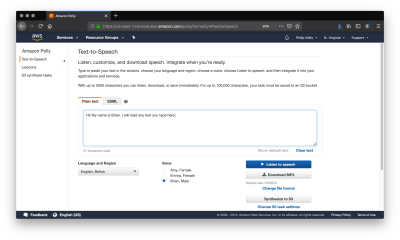

We will begin with text-to-speech using Amazon Polly. For simple exploration, AWS provides a graphical user interface through its online console. After logging in to your AWS account, use the “Services” menu to find “Amazon Polly” or go to https://us-east-1.console.aws.amazon.com/polly/home/SynthesizeSpeech.

Using The Polly Console

You can use the Amazon Polly console to read 3,000 characters (about 500 words) and get an audio stream or immediate download. If you need up to 100,000 characters (about 16,600 words) read, your only option is to have AWS store the result in S3 after it has finished processing, which can take a couple of minutes. At the time of writing, Amazon Polly does not support inputs of over 100,000 billable characters, if you want to convert a longer text like a book you will most likely have to do so in chunks and concatenate the audio files yourself.

A “billable character” is one that the service actually pronounces. Specifically, that means that SSML tags are not billable characters, which we will cover later. For your first year of using Amazon Polly, you get 5 million billable characters per month for free, which is more than enough to run the examples from this article and do your own experimentation. Beyond that, Amazon Polly costs four dollars per million billable characters at the time of writing, meaning that converting a standard-length novel would cost about two dollars.

The console also allows you to change the language, region, and voice of the reader. Though this article only covers English, at the time of writing AWS supports 21 languages and 29 distinct language-region pairs. While most regions only have one or two voices, popular ones like United States English have several options to chose between.

“

I often prefer to use the UK English voice “Brian.” To my American ears, the British accent covers some of the inflections in robotic speech and makes for a smoother listening experience. To be clear, Amazon Polly narrated text is very obviously read by a robot, but the resulting audio is quite listenable.

It is significantly better than the built-in reader that the MacOS say terminal command uses, and is comparable to the speech quality of voice assistants like Siri and Alexa.

Writing SSML

If you want full control over the resultant speech, you can take the time to tag your input with SSML. SSML (Speech Synthesis Markup Language) is a standardized language for representing verbal cues in text. Like HTML, XML, and other markup languages, it uses opening and closing tags. Amazon Polly supports SSML input, and tags do not count as “billable characters.” Alexa skills also use SSML for pre-programmed responses, so it is a worthwhile language to know.

The foundational tag, <speak>, wraps everything that you want read. Like HTML, use <p> to divide paragraphs, which results in a significant pause in the narration. Smaller pauses come from punctuation, and you always have the option to insert pauses of up to ten seconds with <break>.

SSML provides <say-as>, a very flexible tag that supports everything from pronouncing phone numbers to censoring expletives using the interpret-as argument. Consider the options from this tag with the following sample.

<speak>

Call 5551230987 by 11'00" PM to get tips on writing clean JavaScript.<break time="1s"/>

Call <say-as interpret-as="telephone">5551230987</say-as> by 11'00" PM to get tips on writing clean <say-as interpret-as="expletive">JavaScript</say-as>

</speak>Further flexibility comes from the <prosody> tag, which provides you with control over the rate, pitch, and volume of speech. Unfortunately, at the time of writing Polly does not support the <voice> tag, which Alexa skills can use to speak in multiple standard voices, but does support the <lang> tag that allows voices in one language to correctly pronounce words from other languages. In this example, <lang> corrects the pronunciation of “tag” from American to German.

<speak>

Guten tag, where is the airport?<break time="1s"/>

<lang xml:lang="de-DE">Guten tag</lang>, where is the airport>

</speak>Finally, if you want to customize pronunciation within a language, Amazon Polly supports the <phoneme> tag.

“

<speak>

Philip Kiely<break time="1s"/>

Philip <phoneme alphabet="x-sampa" ph="ˈkaI.li">Kiely</phoneme>

</speak>This is not an exhaustive list of the customization options available with SSML. For a complete reference, visit the documentation.

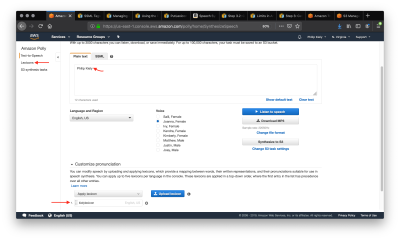

Writing Lexicons

If you want to specify a consistent custom pronunciation or expand an abbreviation without tagging each instance with a phoneme tag, or you are using plain text instead of SSML, Amazon Polly supports lexicons of custom pronunciations. You can apply up to five lexicons of up to 4,000 characters each per language to a narration, though larger lexicons increase the processing time.

As with before, I want to make sure that Amazon Polly says my name correctly, but this time I want to do so without using SSML. I wrote the following lexicon:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<lexicon version="1.0"

xmlns="https://www.w3.org/2005/01/pronunciation-lexicon"

xmlns:xsi="https://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xsi:schemaLocation="https://www.w3.org/2005/01/pronunciation-lexicon

https://www.w3.org/TR/2007/CR-pronunciation-lexicon-20071212/pls.xsd"

alphabet="x-sampa"

xml:lang="en-US">

<lexeme><grapheme>Kiely</grapheme><alias>ˈkaIli</alias></lexeme>

</lexicon>The <?xml?> header and <lexicon> tag will stay mostly constant between lexicons, though the <lexicon> tag supports two important arguments. The first, alphabet, lets you choose between x-sampa and ipa, two standard pronunciation alphabets. I prefer x-sampa because it uses standard ASCII characters, so I am unlikely to encounter encoding issues. The xml:lang argument lets you specify language and region. A lexicon is only usable by a voice from that language and region.

The lexicon itself is a sequence of <lexeme> tags. Each one contains a <grapheme> tag, which contains the original text, and the <alias> tag, which describes what you want said instead. Aliases go beyond pronunciation, you can use them for expanding abbreviations (“Jr” becomes “Junior”) or replacing words (“Bruce Wayne” becomes “Batman”). A lexicon can have as many lexeme tags as it can fit in the 4,000 character limit.

The screenshot shows the plain text that would be mispronounced and the applied lexicon. Use the “Customize Pronunciation” menu to select up to five uploaded lexicons, uploaded from the left navbar tab “Lexicons.” Listening to the speech verifies that my name is said correctly.

Now that we have full control over the resultant speech, let’s consider how to save the output for use in our application.

Saving And Loading From S3

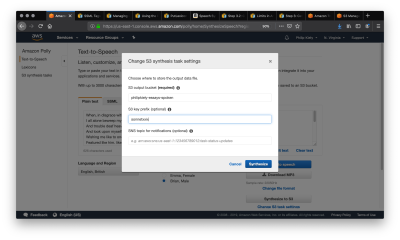

If you want to re-use spoken text in your application, you’ll want to choose the “Synthesize to S3” option in the Amazon Polly console. In this example, I am using the voice “Brian” to perform a surprisingly capable reading of Shakespeare’s sonnet XXIX. We begin by copying in the poem as plain text and selecting “Synthesize to S3,” which launches the following modal.

S3 buckets have globally unique names, and you can enter any S3 bucket that you own or have the appropriate permissions to. Make sure the bucket allows for making its contents public, as that will be required in a future step. You should also set a “S3 key prefix,” which is a string that will help you identify the output in the bucket. After clicking Synthesize and giving it a moment to process, we navigate to the S3 bucket that we synthesized the speech into.

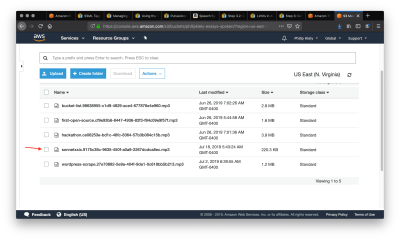

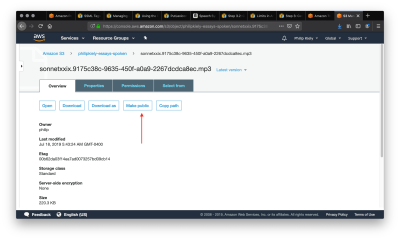

The arrow points to the entry in the bucket that we just created. Selecting that item will bring us to the following page.

Follow the arrow to select the “Make Public” option, which will make the file accessible to anyone with a link. Scroll down and copy the link and use it in your application. For example, you can download the poem here. For many applications, you may wish to pass the url to an html <audio> tag to allow for web playback.

We have covered every necessary component for transforming text-to-speech on AWS. Next, we turn our attention to a more advanced interface that can provide automation potential and save time.

Using The AWS CLI

Back to our hypothetical blog post. The simplest workflow would be to take the final written version of each article, copy it into the console, click the “Synthesize to S3 button,” and embed a download link to the resultant .mp3 file in the blog. Honestly, this is a pretty decent workflow; it is exactly what I do for my personal website. However, AWS offers another option: the AWS CLI.

Make sure that you have installed and configured the AWS CLI appropriately. Begin by entering aws polly help to make sure that Polly is available and to read a list of supported commands. For troubleshooting, see the documentation.

To perform a conversion from the command line, I first copied the poem from earlier into a .txt file. I then ran the following command in terminal (MacOS/Linux):

aws polly synthesize-speech \

--output-format mp3 \

--voice-id Joanna \

--text "`cat sonnetxxix.txt`" \

poem.mp3

In a few seconds, the resulting .mp3 file was downloaded to my machine, ready for inclusion in my CMS or other application. Note the special characters around the --text argument, this passes the contents of the file rather than just the file name.

Finally, for more advanced applications, Amazon Polly has an SDK for 9 languages/platforms. The SDK would be overkill for these examples, but is exactly what you want for automating Amazon Polly calls, especially in response to user actions.

Conclusion

Text-to-speech can help you create more versatile, accessible content. Beginning in the Amazon Polly console, we can transform up to 100,000 billable characters in plain text or SSML, make the resulting .mp3 file public, and use that file in an application. We can use the AWS CLI for automation and more convenient access.

Stay tuned for the second article of the series, we will convert media in the other direction, from speech-to-text, and consider the benefits and challenges of doing so. It will build on the technologies that we have used so far and introduce Amazon Transcribe.

Further Reference

Update: August 7, 2019. Around the date of publication, Amazon announced an improved Neural engine and “newscaster style” speech options available in Amazon Polly. I now recommend that any long-form English content be read by either the EN-US Matthew or Johanna voices as at this time they are the only two that support the newscaster style. After reading this article, you should have no trouble using these options by following Amazon’s guide.

This article was updated on 7th August 2019 to add the above information about newscaster style options. — RA.

Further Reading

- Using AI For Neurodiversity And Building Inclusive Tools

- Conducting Accessibility Research In An Inaccessible Ecosystem

- How To Enable Collaboration In A Multiparty Setting

- Voice Control Usability Considerations For Partially Visually Hidden Link Names

Click here to kickstart your project for free in a matter of minutes.

Click here to kickstart your project for free in a matter of minutes.

Check the frontend report!

Check the frontend report! Start with a free demo —

Start with a free demo —