Professional Team Management Tips For Creative Folks

There seems to be in creative sectors a fear of management and a great divide between creative and “business” people. This is often because the people doing the managing are not business-minded or business school graduates but are rather designers or developers.

Managers in creative industries tend to be staff who have moved up within the company; for example, a junior designer who reaches mid-level, then senior, and eventually ends up running their own team; or a developer who works for himself but gets a series of major contracts, and before they know it they are the Managing Director of a small company. This type of team has many benefits but also some downsides.

Some of these ideas are not new or indeed particularly innovative, but they are often overlooked or even ignored. Below is a selection of key items for discussion within your team. The snippets cover a variety of topics to help managers in creative industries who may not have a managerial background. You may agree with some suggestions and not others, but the aim is to gain a basic understanding of key issues so that you can look at how to improve your team. After all, if you spend all your time producing great work and no time creating a great team, the first will be harder to achieve.

1. Why It Is Important

Good management is vital if we expect our work to be effective. A job goes through several activities and cycles between when it comes through the door and leaves as a nice shiny finished package; and effective management needs to be in place at each stage for the product to be completed on time, to a high standard and within the budget. Time and project management are not the only things to consider, though. Just as important are bringing a team in line with the company’s objectives and motivating the team so that it truly wants the outcome of its creativity to be successful.

As mentioned, managers in creative industries tend to have the background skills associated with their particular field, so they often are familiar with the kinds of problems their teams face day to day, as well as the solutions. Issues often arise, though, when they have to do something “managerial” about it. These designers and developers eventually find that management tasks occupy most of their time, and so making the shift gracefully is important.

Looking over everyone’s shoulders and chipping in an opinion and trying to be involved in every decision can be counter-productive. Let your team shine, and offer guidance and support when needed.

Sometimes you have to try something new to create a better team.

2. Tips And Suggestions

Know Yourself

What kind of manager are you? Knowing yourself first is important before you start managing others. What kind of manager are you? Helping and managing others is hard without understanding what kind of person you are and what areas you can improve in.

There are several approaches to managing:

- Tell. Top-down, you tell them what to do, with no involvement from them. In this style of leadership, information is funneled up, and decisions are funneled down very authoritatively. This style leads to members disagreeing with what they have been told or simply doing what is asked and nothing more.

- Tell/Sell You tell them what to do but try to “sell” them the idea as well. You attempt to sell to your team the benefits of a particular course of action but are essentially telling them to get it done. This style often creates compliant collaborators, people who simply do what has been asked more because of the benefits than because of personal motivation to achieve the objectives.

- Involve. The team feels more a part of it. They are more involved in the direction of their work while still leaving the responsibility of decisions with the manager. Seeking input from the team creates a more enthusiastic team, and sharing ideas often helps generate new ideas.

- Co-create. This has potential to harness the talent of your team members best. The manager sets the objectives, but the method of achieving them is largely decided upon by the team. The manager actively involves the team and take their suggestions, often changing her or his mind in favor of a team member’s suggestion.

A skilled manager needs to be able to balance these styles according to the situation and maturity of the team. Obviously, if a team has served a “Tell” manager for several years, transitioning to a “Co-create” style will take time.

As John Smythe points out in his book “CEO: Chief Engagement Officer” (see reference section below), while the “Involve” and “Co-create” managers are much better at harnessing team skills, they are not necessarily the most suitable for all occasions. For serious business emergencies, a directive “Tell” approach is more effective.

Know Your Team

This is the whole point, after all. If you do not know what drives your team, you cannot possibly begin to get the best out of them. Don’t assume that your team members are motivated by the same factors that drive you.

The team approach has several benefits: distributed workload, balance of strengths, creative problem-solving, full involvement, good motivation, etc. But running an unhappy team can damage your company. Your team should know the reasons behind the work they are creating and should buy into the vision of the company. If your workers come in, do their work, go home and don’t care, then you are unlikely to draw their full potential.

You can use several tools and techniques to get to know your team better. These are detailed later in the article.

Invest in Your Team and Push Its Boundaries

A team needs to be – and feel – invested in the work it does. Being able to judge when to develop certain skills in team members and learning what they themselves want to develop is important. Kenneth Blanchard states in his book “One Minute Manager” that 50 to 70% of a company’s money is spent on wages, yet only approximately 1% is spent on training.

More is spent on maintaining the office that on maintaining and developing the staff. So many managers and businesses spend so much time completing tasks that they rarely stand back and ask, “Is this the most effective way to work on this task?” It is the age-old problem of spending too much time working in the business and forgetting to work on the business.

Forcing a team member to learn a certain skill or fill a certain role because it is lacking in the company is usually not the best solution. For example, give a brand designer a book on how to improve their typography skills, and they will likely read it in their every waking moment. If they have no interest in programming, and you give them a book on ASP.NET in C# just because the company needs to fill that gap, they will struggle with it, and then their commitment (along with their happiness) will drop. Learning what makes your team tick then is vital.

All Teams Need to be Stretched and Challenged, Not Pushed

Stretching and challenging your team members helps them develop and maintain their interests. But monitor how much your team members are being challenged, because stretching them too hard will have negative consequences. “Pushing” isn’t the right word. Pushing a team implies that someone is behind it pushing. Remove that force and the team will likely fall back into its previous routine. A team needs to be stretched and should also want to be stretched.

So stretching within our comfort zones is important. Each person has a comfort zone, a set of tasks that they are comfortable doing and that they do well. Beyond is the panic zone, where they are anxious that they will not be able to perform a task to a sufficient standard. Between those two is the stretch zone.

This is where a manager wants their team to be most of the time. When team members get tasks that challenge them, their comfort zone is stretched and their panic zone shrinks. They learn new skills and develop the confidence to complete tasks they previously could not.

Goals and Targets: What Drives Your Team?

Setting goals – personal, team and company goals – is useful. This exchange from Alice in Wonderland illustrates the point well:

Alice: Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here? The Cat: That depends a good deal on where you want to get to Alice: I don’t much care where. The Cat: Then it doesn’t much matter which way you go. Alice: …so long as I get somewhere. The Cat: Oh, you’re sure to do that, if only you walk long enough.

If you don’t know which direction to go in, then how will you know when you have reached your destination? You need some sign that you have achieved your goal. Most people have some idea of where they want to be in five years. By writing down what you hope to achieve, you formulate a checklist. Without that checklist, you have nothing to work towards or anything to measure your success.

Milestones help you track success. Learning each team member’s goals is useful in assessing what motivates them. By sharing the company and team’s goals with each member, you show trust and gain theirs. You also get a sense of the path each member wants to pursue and are able to guide them in that direction if appropriate.

For example, if a junior developer states that in five years, they would like to be fluent in ASP.NET and running their own team, you automatically gain insight into how you can help them train and build the foundation for that future.

Motivation

One point that bears repeating is that your team members may not be motivated by the same things that drive you. Inspiring a team member to do something they do not want to do is very hard. A more productive solution would be to learn what motivates them and allow them to act on it in a way that benefits the team.

Several books on management assert that creating an atmosphere in which team members feel personally motivated is better than trying to directly motivate them yourself. Create an environment in which team members actively seek to solve problems without being asked, in which they want to expend energy and solve problems to make the product or service they are working on the best it can be, thus benefiting themselves, the team and the company as a whole.

“No one can persuade another to change. Each of us guards a gate of change that can only be opened from the inside. We cannot open the gate of another, either by argument, or by emotional appeal.” Marilyn Ferguson, author.

Forcing someone to change their behavior or motivations is often demoralizing and even leads them to argue with or resent you, depending on their personality. Take a staff member who is constantly late. Rather than discipline them and focus on their tardiness, focus on why they would want to be there. If they have a purpose and motivation to be there, they will more likely make the effort to arrive on time.

Change and Trust

A lack of trust can be the biggest barrier for any team. Building trust and shared values on a team is critical. The members need to feel reassured that you are looking out for their best interests. An owner whose team members know would sell the company for profit with no regard for them will not gain their trust. Likewise, a company whose top-level managers give the appearance of stability, only to make 80% of the team redundant, won’t be able to hold the trust of the remaining members without careful discussion and explanation.

Therefore, managing major changes carefully is important. Consider the happiness of the team, because an unhappy, distrusting team makes for a work force that is paranoid about its job security and thus less productive.

Three major barriers to a team’s happiness and success are change, loss of control and lack of trust. How you manage these issues when they arise is critical. Much research has been done into change control and trust on teams. See the book on building trust by Robert C. Solomon and Fernando Flores in the reference section below for more information.

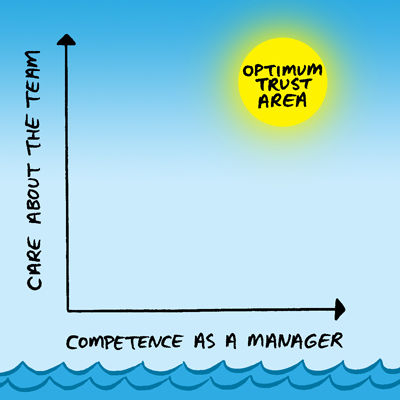

The diagram below shows the balance a manager needs to strike to gain the trust of their team. You can show you care about a team, but if you are incompetent as a manager, you will not be trusted. You can be competent as a manager, but if you do not show that you care, you will not be trusted. To truly gain the trust of your team, you need to show that you are competent at what you do and that you care about your team and have their best interests at heart.

Interaction with Your Team: Communication

Good communication is vital in any organization and is the difference between success and failure. Maintaining strong communication channels with your team is essential, or you may find yourself playing the telephone game, in which information is miscommunicated as it is passed along. A team has to know exactly what is required of it and by when.

Things can and will go wrong along the way, but communicating and regrouping in time when something is going off-track is a sign of a strong team. You cannot train someone to predict all problems, but they can learn to flag problems when they occur in time to work around or resolve them.

As a test, try an internal email-free day. Emails are a useful tool for passing around data, instructions and feedback, but how often have you emailed someone on the same floor, in the same office or even beside you. Email is a one-way channel insofar as the recipient gets your message but cannot interact with you or ask about your message at that very moment, nor do they have the benefit of gauging your facial gestures and body language.

While difficult, try working a whole day free from internal email. Not only will this force the staff to actually speak to one another, but it will allow them to debate questions with each other face to face. It will also improve their memory and note-taking skills because they will now have to remember things that they are used to receiving in hard copy. See the book by Dan Heath on making information stick in the reference section below.

“Sorry, I Just Don’t Have Time”

If you as a manager or team member are asked for help, do not simply reply, “Sorry, I don’t have time.” That says that you consider your tasks to be more important than theirs. Everyone has the same number of hours in the day. Prioritizing and giving help when needed is important. You may actually feel as though you have absolutely no time to spare, but if the task would hold your team up for an hour but take only five minutes of your time, you may want to reconsider.

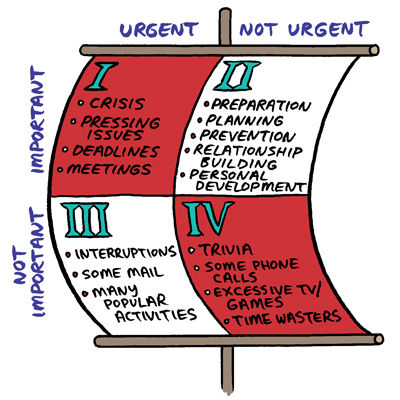

Stephen Covey recommends a time-management matrix, shown above, which splits tasks into “urgent” and “not urgent,” and “important” and “not important.” He says, for example, that some people “spend a great deal of time in ‘urgent, but not important’ Quadrant III, thinking they’re in Quadrant I. They spend most of their time reacting to things that are urgent, assuming they are also important. But the reality is that the urgency of these matters is often based on the priorities and expectations of others.” Use this matrix to filter your day-to-day tasks and determine what really needs to get done and what may not be as important as it first appeared.

What Do You Want Your Team to Get Out of Meetings?

Hold team meetings as often as needed, but keep them concise. While obvious, this advice is often not followed. Holding a Monday meeting, for example, to let the team know what is required of it that week can be useful. Meetings should cover three key areas:

- Sharing information: what’s happening, events, deadlines.

- Focusing resources: who is doing what?

- Energy: the team should emerge from the meeting with more enthusiasm and understanding of what is expected of it than when it entered.

Store this information somewhere accessible, so that all team members can refer to it. This also allows the team to review earlier periods, to see what targets it hit, what remains outstanding and so on. And if the team misses a target, they can discuss the reasons for it and learn lessons from it. It doesn’t matter “who messed up” or “who is to blame”; think more of “what can we learn from this so that it doesn’t happen again this week.”

That Blasted Facebook!

One issue that many managers struggle with, related to motivation, is staff who appear to be surfing the Web instead of doing work. With the rise of social networks, we have so much at our fingertips to distract ourselves with. This can easily frustrate a manager, until they alter their perception slightly. An effective manager focuses on achievement, not activity. A person could occupy themselves with work non-stop for eight hours a day and appear to be productive but still not perform to their potential. People need recovery time, and everyone’s recovery time is different.

For example, Joe finds he is at his peak when he works for an hour, then makes coffee and checks Facebook updates for 10 minutes, and then returns to work. Janet, on the other hand, prefers to work under pressure, going non-stop from 9:00 to 12:00, then taking a full hour for lunch, instead of half an hour, to get some fresh air and recharge.

Whatever works for the individual. Understand what your team members like to do for downtime and what they have to do on an average day to improve their performance. By working non-stop, they are not working to their maximum potential.

Ground rules are important. Your team has to know what is expected of it. You may even want to collaborate with members on setting ground rules for how they work. After all, they know what is best for them, not you. If they agree to a deadline and miss it, then you are justified in looking at how much downtime they take, discussing what went wrong and taking measures. But don’t discipline a team member for appearing not to be working. If they are hitting their targets and producing work of an acceptable standard, while occasionally surfing the Web, then fine. Achievement, not activity.

3. Team Management Tools And Techniques

Several tools are on the market to help with management, most for time and project management than for team and personnel management. However, a few may prove useful to you.

DISC Behavioral Profile

The DISC behavioral profile is a popular and effective tool for team management. The profiling tool identifies the inherent strengths and challenges of individual working styles and guides you on building effective relationships with people who have styles different from yours. After all, your team’s effectiveness largely depends on your relationship with the members and the relationships between members.

No one result of this test is better than another, but some styles may be more appropriate for certain situations, and an effective manager will adjust their style without confusing the team. For example, a team would probably be confused by a manager who is usually a very high D (highly focused on the bottom line and authoritative, even argumentative) and suddenly switches to high S + C (unable to make a decision without going off to weigh the options). The important thing is how you use these results to get the best out of your team. (See the notes below and reference section for in-depth explanations of each style’s characteristics.)

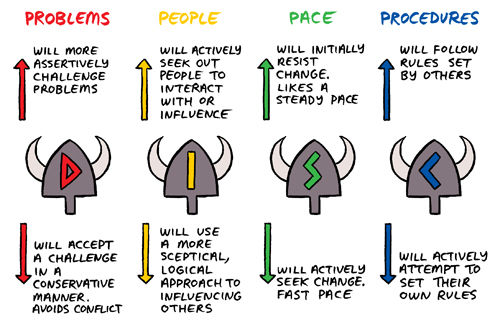

As you can see in the chart below, someone with a high D assertively challenges decisions and problems if need be, whereas someone with a low D generally seeks consensus and avoids conflict. Identifying the makeup of team members’ behavioral profiles can yield valuable insights that help improve performance. For example, a developer with a high D style challenges ideas and methods of working and tends to work better at the beginning of a project and then trail off at the end as they seek a new challenge.

Someone with a high S + C style is more likely to do things correctly the first time and stick to methods they have tried and know work. So, pairing these two personality types toward the end of a project can bring two advantages: the high D can have their worked checked by the high S + C to ensure high quality, and if the high D has tried a new technique, they can put it to the test with the high S + C, who may not have tried it before.

Note the focus of each style of working – D: problems; I: people; S: pace; C: procedures; – and some of the characteristics of the highs and lows of each style.

Pareto Principle

The Pareto Principle (or the 80⁄20 rule) helps to focus effort on the most effective, essential and often profitable tasks. This principle posits that 80% of the rewards or results or profit or outcome come from only 20% of the effort or time or contributions. For example, a manager may recognize that the beginning and conclusion of a project are the most important stages and that focusing effort on them benefits the project enormously.

Reviews

Reviews are a critical tool in managing. While most managers conduct them, simply having an annual appraisal in which you say, “You are doing X well. You may want to improve X, Y and Z? How do you feel about that?” is not enough. Use these occasions as an opportunity to really delve into the performance of the team member and assess their happiness. Once these have been ascertained, then you can look at what skills they would like to develop next.

Find out what makes them tick. Find out how they think the team would perform better. This goes back to the “Co-create” method of managing. But if you conduct only a single annual review, that is not the time to raise concerns about a team member’s performance. Waiting all that time to discuss the problem is, in fact, quite disrespectful. Discuss it earlier on, before it gets out of hand, so that the member has time to come up with a plan to improve, which you can then assess at the annual review.

One-Minute Manager Techniques

The One-Minute Manager is a series of books by Kenneth H. Blanchard (reference below). Rather than lay out theories, the books tell the story of a young man in search of the perfect manager. The title is not meant to suggest that you can learn how to become a manager in one minute. Rather, it refers to a manager who gets results quickly (i.e. in one minute). The book covers some key techniques that you can develop and apply to certain situations, such as the following.

One-Minute Goal Setting Once a project begins, set out the goals that the team member has to work towards, as well as the standard of performance you expect them to meet. This can be kept to a single sheet of paper, no more than 250 words per goal. The idea is that you should be able to read each goal in under a minute.

Both the manager and team member should keep a copy for reference. This goes back to the Pareto Principle: setting goals for every single bit of work and milestone will not likely be beneficial. Blanchard states that “80% of your really important results will come from 20% of your goals.” This requires not only that the goals be clearly understood by everyone involved but that the standard of performance be clearly set out, too.

Blanchard gives the example of a staff member going to their manager and saying that they have a problem with how something is done. The One-Minute Manager asks him what the solution to the problem is, to which he replies that he is unsure. The manager then says:

”‘If you can’t tell me what you’d like to be happening,’ he said, ‘you don’t have a problem. You’re just complaining. A problem only exists if there is a difference between what is actually happening and what you desire to be happening.‘”

By getting team members to solve their own problems, not only do you give them responsibility and a sense of accomplishment, but you ensure that minor issues are not constantly passed up the chain to be fixed. If asked the right question, each member of staff would be able to solve their problem themselves. They just need to internalize the process of working through the problem and coming to a solution that achieves the desired outcome.

Blanchard uses bowling as a good analogy. People like bowling because they can see the pins in front of them, and when they knock them down, they see the results and praise themselves. If you hid the pins or removed them, where would be the fun in that? As managers, we need to clearly set out where the pins are and how many need to be knocked down, and we need to give feedback on the person’s performance afterward.

One-Minute Praising This technique is about acknowledging when a team member does something right, instead of pointing out when they’ve done something wrong. If you tell your team that you will praise them when it does something right and reprimand it when it does something wrong, there will be no surprises. Everyone knows what to expect.

If you praise people immediately when they do something right, being specific about what exactly they did well, you demonstrate that you know what is going on and are on top of everyone’s performance. Expressing how you feel about them doing well and how it helps the organization and letting that feeling sink in for a moment can significantly help team relationships, morale and productivity.

Do more of these one-minute praising sessions when an employee starts at your company or on your team, begins a project or gains new responsibility, because those are the times when you are more likely to have different ways of measuring praiseworthy performance. If the member restructures code to optimize how particular chunks are searched, they may feel this deserves praise but you may not see it as being so important. This way, the member learns when to praise himself and will be motivated to earn their manager’s praise for other tasks.

During training, praise new employees when they do something more or less right. Most managers wait until team members do something spot on before praising them, which could keep some of them from becoming high performers, because the manager’s focus is on what is still wrong rather than on what is going well.

Blanchard gives the example of a child learning to walk. You do not stand them up for the first time and say “Walk,” and then punish them when they fall. You praise them for standing on their own. And when they take one step apprehensively, you praise them again, and the child continues to makes progress until they are capable of walking unaided. That is when you move on to the next (smaller) goal and praise.

One-Minute Reprimands While One-Minute Praising is about pointing out when someone does something right, the One-Minute Reprimand has its place, too. It is the third secret in the One-Minute Manager’s formula for success. If a person has been at a job for a long time and makes a big mistake, they should expect the One-Minute Manager to respond, and respond quickly. Every established team member should know their job well. Simple mistakes are fine; after all, mistakes happen.

But when one does happen, and the One-Minute Manager has gathered the facts about it, they will discuss it with the team member face to face. They will make eye contact and tell the team member precisely what they did wrong. They will then share how they feel about the mistake: are they frustrated, angry, disappointed? The conversation usually takes less than a minute.

Once the mistake has sunk in, the One-Minute Manager lets the team member know how competent they consider them to be and that the only reason they are disappointed, angry or frustrated by the mistake is because a team member with so much knowledge and competence should have avoided it. The manager then explains that he looks forward to speaking with the person soon under different circumstances (i.e. not for the same mistake). This will hit home for the team member that they should be aware of that particular mistake and avoid it in future.

Five things to remember with One-Minute Reprimands are:

- A reprimand should be made as soon as the mistake happens. Even if your business is doing well otherwise and you are feeling good about a project’s success, do not overlook mistakes. Do not keep a shopping list of mistakes made by an employee over a week, month or year and then explode on them all at once. If you do, the recipient won’t really absorb what you’re saying and may get defensive and even de-energized.

- Specify exactly what the mistake was. Clarify what the problem is to show you are on top of things and that sloppiness will not be overlooked. Do not reprimand on hearsay. Get your facts straight, and show you care enough to be tough.

- Criticize the behavior, not the person. Overt personal attacks make people defensive and make them want to pass the blame. By focusing on their behavior or performance, you appear fair as a manager.

- Be consistent. Do not reprimand one team member for making a mistake and then not reprimand someone else who does the same thing. By being consistent with both reprimands and praise, you gain the trust of your team.

- Be willing to laugh it off. Team members need to be able to laugh about both praise and reprimands. For example, a manager reprimands a team member face to face, and then the member calls the manager shortly after, saying, “I just realized that you forgot to add some praise after your reprimand and say what you think I do well.” This example is perhaps a bit exaggerated, but it illustrates that the member does not take the reprimand personally and can joke about it with the manager if appropriate.

Conclusion

We have covered several topics here in brief. Hopefully, you will be better able to spot problem areas in your team’s dynamic and take appropriate steps. Not all of these points are relevant to every situation, so please comment below with your own points, examples or reasons why any of these points are not relevant to your particular situation.

Ultimately, the point is to take stock of how you do things. If what you’re doing works, and you are 100% confident that you are getting the best from your team, then carry on. Keep track of your and their performance, and watch out for any areas for improvement. If anything comes up, then investigate it further and see how you can get optimum results while keeping everyone happy.

Further Resources

Below are some resources that you can use to further apply the ideas we’ve discussed here. If you know of any others, please comment below.

- The Creative vs. The Marketing Team: Yin And Yang, Oil And Water

- How To Build An Agile UX Team: The Culture

- How To Build Digital Capacity And Attracting Talent

- Better Dependency Management In Team-Based WordPress Projects With Composer

Illustrations created by Adam Cadwell, a Comic Artist and Illustrator based in Manchester, UK.

Register Free Now

Register Free Now

Register for free to attend Axe-con

Register for free to attend Axe-con

Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App