Decision-Making Models In Web Development

When was the last time you made a decision? A big one. What was the outcome? Was it good, and how did you get to that outcome? Every day we all make plenty of decisions without a thought to how we structure them or the basis on which we make them. We simply make them. We’re lucky that we work in an industry in which erroneous decisions may have serious financial consequences but rarely, if ever, costs lives.

In fields such as aviation and health care, bad decisions can have massive repercussions. As a result, a lot of cash has been spent studying the human factor and developing methods of reducing error. After all, you’d like to think that the person in the cockpit is fully capable of caring for an expensive jet and its passengers.

You may also want to take a look at the following related posts:

- Why Design-By-Committee Should Die

- How To Convince The Client That Your Design Is Perfect

- Web Designers, Don’t Do It Alone

- How To Be A Samurai Designer

These studies have led to many conclusions and insights on human behavior, and they have also helped to develop formal decision-making and error-checking processes for people involved in making big decisions. These are models we can learn from and apply to our everyday choices, big and small.

Why Do We Need Decision-Making Models?

(Image credit: Julia Manzerova)

Quite simply, we don’t. We’re all quite capable of making perfectly good decisions on our own with no outside help. However, we also “don’t need” a 960 grid to structure a great Web design, and we don’t need a validator to make clean, valid website code, but they both help ensure that our output is as good as it should be.

While some people naturally make good decisions, others struggle and need the support of a model or framework, in the same way that some people naturally make balanced Web designs and others prefer the help of a layout grid.

Also, be aware that decision-making models aren’t applied exclusively to rushed decisions on urgent problems, such as unexpected server outages. They can be used to approach any issue, from making an intricate pitch to a client to building or redesigning a website.

Bad Decisions and Good Decisions

Good decisions can save both time and money, and experience, forethought and planning can help you make them. The difference between bad and good decisions is not always clear-cut, and our opinion of our own decisions will often change in hindsight. But making measured and well-considered decisions will make us more comfortable with the course we have chosen and more confident in future decisions.

Stress and Decision-Making

We make decisions under a variety of pressures all the time: workload volumes, financial commitments, deadlines. No surprise that the quality of decisions made under stress is not as good as the quality of those made in calmer times.

By applying a structure, we can clear our heads in stressful times and make effective decisions when needed.

Teamwork

Formalizing the decision-making process can be really effective among groups.

Most people in the Web design industry regularly work on teams, whether with other designers and developers or clients. These collaborations often come with very large communication barriers, such as remote working and teleconferencing and even language differences, each of which has its own problems.

Teleconferencing presents some of the biggest communication barriers. (Image credit: Stuart Cummings)

A formal decision-making process helps to ensure that everyone understands what is being done and why it is being done, and it gives them sufficient time and opportunity to give effective input.

Basic Models

Within the aviation, health care and corporate world, you’ll find a few key decision-making models, all of which aim to provide a sensible, intuitive framework in which to structure better decisions.

SHEL

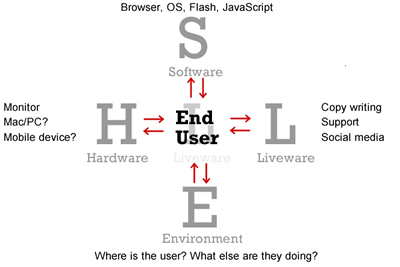

SHEL is an acronym for Software, Hardware, Environment, Liveware and is used to assess interactions in various situations.

The graph is normally drawn out as a cross, with the central liveware (in our case, the end user) in the middle. It can be used as a brainstorming and planning tool to assess the interaction between the elements in the model and the central liveware.

For Web design, the diagram could be annotated to show these key areas:

A SHEL diagram showing the end user in the middle and including Web design considerations.

Using the SHEL model reinforces the point that the end user should be the primary consideration in any planning process.

The diagram above shows a typical website scenario, but you can use SHEL to cover all of the areas of any project and to check that you have all the information needed to proceed.

Using it as a brainstorming tool with clients, we can ensure that we fully understand the situation and task at hand and can clarify that we are both looking at the same influence factors.

By considering every aspect of an interaction or problem, we minimize the impact of any surprises and modifications down the line and help ourselves make better decisions.

DODAR

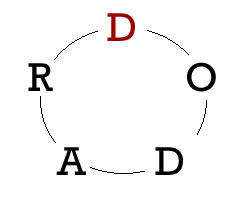

The DODAR process is often represented as a circular flow.

DODAR is a primary decision-making tool and stands for Diagnose, Options, Decide, Assign, Review. It captures the five key areas of any decision-making process.

Diagnose is the first step to solving any problem or decision. Find out the problem and what causes it. Use all available resources to identify the problem or to confirm the lack of one.

One of the main reasons for error in decision-making is “confirmation bias,” whereby we make a decision based on a few factors that favor our initial impression, without fully evaluating the problem. How often have you said, “Oh yeah, I know why that is. Won’t take a minute.” And then you find out that the problem isn’t what you thought at all and that the solution will take a little longer. Use the diagnosis stage to make sure you are certain of the issue at hand, by both proving and disproving any ideas or theories.

Options, once you’ve decided what the problem is, look at the options available to you. Assess whether the problem is urgent or can be left for a while. But remember, just because it can be left for a while, doesn’t mean it should be!

Decide on a course of action that you think is sensible, and check this course of action with the other parties involved.

Assign appropriate tasks to people who are capable of carrying them out.

Reviewing is the most important stage of all: making sure everything is going according to plan, and making sure you’re getting the results you expect. Question all of your sources again, and if things aren’t as they should be, then find out why and, if needed, return to diagnose the problem and run through the process again.

As a tool, DODAR is often overlooked because it follows such an obvious and intuitive decision-making process. But by using it as a mental check, you can confirm that you have come to a sensible and well-considered decision.

Facilitating Effective Communication

You can see that using a basic decision-making model on your own is a relatively easy process. But the real value of this structured process is in using it with other people.

A decision-making model helps teams focus on the task at hand together, whether it be evaluating a website redesign or fixing a server bug.

We often struggle to communicate, and our working environment can have huge barriers to effective communication. Remote working and teleconferencing can be the most restrictive because they reduce the communication and interaction available to us to very few dimensions. So, by working in a sensible shared framework, we are able to make effective group decisions despite these restrictions.

By using every stage of the DODAR process to confirm evaluations, assumptions and decisions with others before moving to the next stage, we are able to keep everyone on the same page.

A Group DODAR Example

When looking at any problem, encouraging the group to work through the process together aids everyone’s understanding of the task.

Take a client who is meeting to build a new website. The first step would be to diagnose what needs to be done and why. Does the client need a CMS? Why? Are there hosting issues related to traffic volume or security? Look at your SHEL model here to ensure that each base is covered.

Once you agree on the task, you can assess the options. Will you use WordPress, ExpressionEngine or something else? Will you host it on your main server or do you need a dedicated one?

When you’re both happy with the options, you can then begin to decide on them. You can also look slightly ahead to the next stage of assigning tasks, if relevant.

Having worked through the problem and decided how the website will be built, you can then determine who will do what by assigning tasks and deadlines. Will you write the copy or will the client? Who will supply the photos and artwork?

The last stage is review, which can take one of two forms. First is the more immediate analysis of the process that you have just gone through. Are you both happy with the decisions you made and the tasks you are set to carry out? The second form is to set targets for ongoing review throughout the project; i.e. set deadlines, review dates and targets for those dates.

NITS Brief

A NITS brief is a quick communication framework that is typically used as an emergency brief. But it can be a great mental check list when you want to communicate a task or problem to a colleague or client.

NITS stands for Nature, Intentions, Time, Specials:

- Nature relates to the nature of the problem or task. What is it and why did it happen?

- Intentions are your intentions, or what you hope will be carried out to solve the task.

- Time is either the time it will take to carry out the actions or the time you would like them to be carried out.

- Specials is for anything unusual or unexpected. For example, would a particular colleague normally be expected to do something else? Will they need to contact a different person than usual?

As an emergency brief in the airline industry, this is often used to communicate information from, say, the pilot to a flight attendant. Any form of emergency situation can be easily handled by telling the attendant the nature of the emergency, what the pilot plans to do, how long it will take to do it and whether passengers can expect anything unusual in this situation.

In the less critical world of the Web, this is still a great mental check list. If a few clients are ringing about a server outage, a quick NITS brief will tell them all they need to know:

- Nature: it’s a server outage.

- Intentions: you are rebooting and checking for errors.

- Timing: it will be back up in five minutes.

- Specials: clients won’t have email for ten minutes.

By using the NITS structure and conveying the problem or task in a sensible and easily understood way, you ensure that all bases are covered.

The brief can also be used as a listening and information-gathering tool. For example, when a client rings you with a problem, you would first establish the nature of the problem, find out what they would like you to do about it, estimate the time frame to get it done, and then convey anything else that is unusual for the kind of work you do for them.

Rather than merely confirm their telephone number, read back your brief to check for errors. If you’ve taken notes using the NITS structure, quickly read them back to the client to make sure you haven’t misunderstood anything.

Trapping Errors

Decision-making doesn’t have to start when you’re in hot water and everything has fallen apart. It should be an inherent part of the planning stages of every project, to ensure that potential problems are mitigated. Error recovery and error prevention should be integral parts of every project.

Swiss Cheese Model

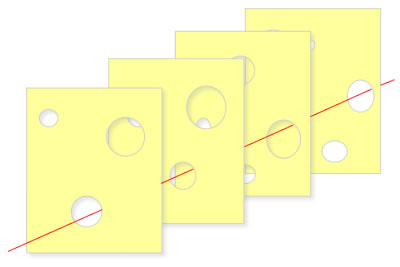

James Reason’s “Swiss cheese” model is widely used in the aviation and medical industries to identify how both latent (or dormant) failings and active (quick, often one-off) failings of a system can lead to serious and sometimes catastrophic problems.

Reason’s Swiss Cheese model shows that when errors in separate layers are not caught, they result in a complete failure.

The model is based on the understanding that each layer of protection can be as secure as possible but still have holes. At each layer, the errors on their own are addressed and do not pose serious trouble; but in certain circumstances, all of the errors on the various levels will align to create a much bigger problem. While similar to a domino effect, the problems do not necessarily have to cause or result from each other or be linked in any way. Circumstances simply conspire to create a situation that goes quickly beyond rescue.

Such situations often result from both latent and active failures, rather than just one type. Latent failures are those that exist but go unnoticed for some time: unstable code or open loops, for example. Active failures are apparent and cause problems directly: for example, a traffic spike.

The Herald of the Free Enterprise, which capsized in the North Sea, is considered a classic example of Reason’s model. No single failure on its own was enough to capsize the boat; but combined, they had disastrous consequences. (Image credit: Wikipedia)

Trap, Mitigate, Avoid

We obviously cannot account for every possible eventuality, so by using a three-step model of error management, we should be able to protect ourselves from error chains.

Whenever we encounter an error or the possibility of an error, we can apply the simple thought process of trap, mitigate and avoid.

Most errors should be trapped as soon as they are detected. This is most often done through techniques such as form validation, by which we trap any errors made and display a message to the user, thus preventing errors from affecting the system.

Errors that cannot be trapped should be mitigated. This includes threats from malicious elements, such as SQL injections and other hacking attempts.

Catching procedures that are present in various programming languages is an example of basic error mitigation. While we are essentially trapping an error in certain parts of our code, we are allowing the error to happen and mitigating its effects by catching it.

Finally, any remaining errors should be avoided by not allowing problems to develop into areas beyond your control, such as setting sensible firewalls and memory limits.

To avoid errors on websites, we need to avoid making our code do things it shouldn’t do; for example, by using noscript tags to ensure we do not encounter errors when running JavaScript. Basic error pages such as 404 and 501 also ensure that our website doesn’t exceed its boundaries.

Check Lists

Check lists are already widely used in the development industry, and rightly so because they are one of the most effective methods of preventing and recovering from errors. They fall into two main categories.

Say and Do

With this model, you read each item on the check list and then carry out the appropriate action. It can be used to prevent and recovery from errors.

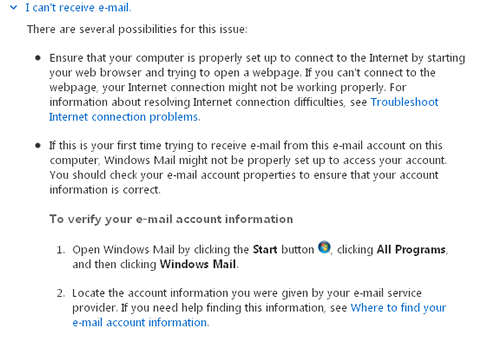

Prevention is exercised by following step-by-step instructions. The error recovery process usually presents a number of options based on your response to a check. For example, if x, then do y; if not, then do z. The most common example on the Web is troubleshooting.

Troubleshooting page on Windows Live Mail.

The Microsoft troubleshooting pages follow the form of a say-and-do checklist or, in this case, read and do. They recommend an action to carry out and offer further considerations based on the result of the action.

Do and Check

The second type is an “after the fact” check list, in which a particular task is already done and its completion is checked against certain criteria. This is a tick-box exercise, as found on website launch check lists.

Typically, these follow the completion of a memory drill, but in our industry they usually follow the completion of a major action, such as a Web project.

Formalizing routine processes is worthwhile, because they prevent problems for those who are unfamiliar with a procedure and those for whom a procedure has become repetitive.

Making clients aware that you have these processes in place also instills confidence that you are always working from best practices and ensuring that your products always meet high standards and specifications.

Further Resources

You may be interested in these further articles and related resources:

- Fundamental Human Factors Concepts, UK Civil Aviation Authority publication.

- Human Factors, on Wikipedia.

- Error Models, on Wikipeida.

- Human Factors, on Wikiversity.

- Human Error Models and Management

- MS Herald of Free Enterprise, on Wikipeida

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

Register Free Now

Register Free Now

Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers