What To Do When Your Website Goes Down

Have you ever heard a colleague answer the phone like this: “Good afterno… Yes… What? Completely?… When did it go down?… Really, that long?… We’ll look into it right away… Yes, I understand… Of course… Okay, speak to you soon… Bye.” The call may have been followed by some cheesy ’80s rock ballad coming from the speaker phone, interrupted by “Thank you for holding. You are now caller number 126 in the queue.” That’s your boss calling the hosting company’s 24 hour “technical support” line.

An important website has gone down, and sooner or later, heads will turn to the Web development corner of the office, where you are sitting quietly, minding your own business, regretting that you ever mentioned “Linux” on your CV. You need to take action. Your company needs you. Your client needs you. Here’s what to do.

1. Check That It Has Actually Gone Down

Don’t take your client’s word for it. Visit the website yourself, and press Shift + Refresh to make sure you’re not seeing a cached version (hold down Shift while reloading or refreshing the page). If the website displays fine, then the problem is probably related to your client’s computer or broadband connection.

If it fails, then visit a robust website, such as google.com or bbc.co.uk. If they fail too, then there is at least an issue with your own broadband connection (or your broadband company’s DNS servers). Chances are that you and your client are located in the same building and the whole building has lost connectivity, or perhaps you have the same broadband company and its engineers have taken the day off. You will need to check the website on your mobile phone or phone a friend. To be doubly sure, ask your friend to check Where’s It Up? or Down for Everyone or Just Me?, which will confirm whether your website is down just for you or for everyone.

If the website is definitely down, then frown confusedly and keep reading. A soft yet audible sigh would also be appropriate. You might want to locate the documents or emails that your Internet hosting service sent you when you first signed up with it. It should have useful details such as your IP address, control panel location, log-in details and admin and root passwords; these will come in handy.

2. Figure Out What Has Gone Down

A website can appear to have gone down mainly for one of the following reasons:

- A programming error on the website,

- A DNS problem, or an expired domain,

- A networking problem,

- Something on the server has crashed,

- The whole server has crashed.

To see whether it’s a programming error, visit the website and check the status bar at the bottom of your browser. If it says “Done” or “Loaded,” rather than “Waiting…” or “Connecting…,” then the server and its software are performing correctly, but there is a programming error or misconfiguration. Check the Apache error log for clues.

Otherwise, you’ll need to run some commands to determine the cause. On a Mac with OS X or above, go to Applications → Utilities and run Terminal. On a PC with Windows, go to Start → All Programs → Accessories and choose “Command Prompt.” If you use Linux, you probably already know about the terminal; but just in case, on Ubuntu, it’s under Applications → Accessories.

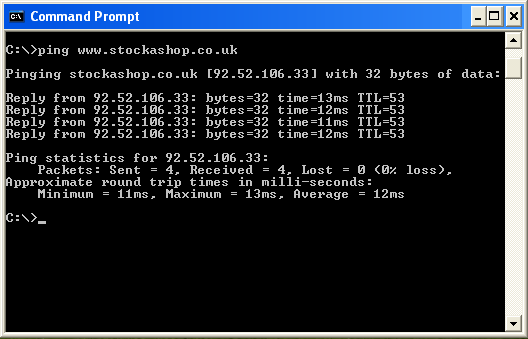

The first command is ping, which sends a quick message to a server to check that it’s okay. Type the following, replacing the Web address with something meaningful to you, and press “Enter.” For all of the commands in this article, just type the stuff in the grey monospaced font. The preceding characters are the command prompt and are just there to let you know who and where you are.

C:> ping www.stockashop.co.ukIf the server is alive and reachable, then the result will be something like this:

Reply from 92.52.106.33:

bytes=32 time=12ms TTL=53

Ping command from a Windows computer.

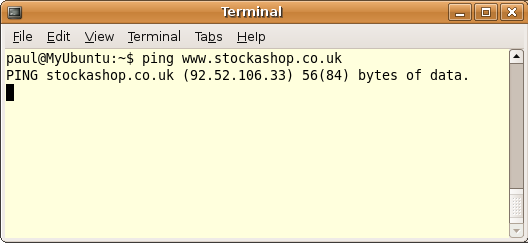

On Windows, it will repeat four times, as above. On Linux and Mac, each line will start with 64 bytes from and it will repeat indefinitely, and you’ll need to press Control + C to stop it.

The four-part number in the example above is your server’s IP address. Every computer on the Internet has one. At this stage, you can double-check that it is the correct one. You’ll need to have a very good memory, or refer to the documentation that your hosting company sent you when you first signed up with it. (This article does not deal with the newish eight-part IPv6 addresses.)

For instance, my broadband company is sneaky and tries to intercept all bad requests so that it can advertise to me when I misspell a domain name in the Web browser. In this case, the ping looks successful but the IP address is wrong:

64 bytes from advancedsearch.virginmedia.com

(81.200.64.50): icmp_seq=1 ttl=55 time=26.4 ms

Note that ping might also show the server name in front of the IP address (advancedsearch.virginmedia.com in this case). Don’t worry too much if it doesn’t match the website you are pinging — a server can have many names. The IP address is more important.

Assuming you’ve typed the domain name correctly, a bad IP address indicates that the domain name could have expired or that somebody has made a mistake with its DNS settings. If you receive something like unknown host, then it’s definitely a domain name issue:

ping: unknown host www.nosuchwebsite.fr

In this case, use a website such as Who.is to verify the domain registration details, or run the whois command from Linux or Mac. It will at least tell you when it expired, who owns it and where it is registered. The Linux and Mac commands host and nslookup are also useful for finding information about a domain. The nslookup command in particular has many different options for querying different aspects of a domain name:

paul@MyUbuntu:~$ whois stockashop.co.ukpaul@MyUbuntu:~$ host stockashop.co.ukpaul@MyUbuntu:~$ nslookup stockashop.co.ukpaul@MyUbuntu:~$ nslookup -type=soa stockashop.co.ukIf nothing happens when you ping, or you get something like request timed out, then you can deepen your frown and move on to step three.

What a non-responding server looks like in a Linux terminal.

Alternatively, if your server replied with the correct IP address, then you can exhale in relief and move on to step five.

Note that there are plenty of websites such as Network-Tools.com that allow you to ping websites. However, using the command line will impress your colleagues more, and it is good practice for the methods in the rest of this article.

3. How Bad Is It?

If your ping command has timed out, then chances are your whole server has crashed, or the network has broken down between you and the server.

If you enjoy grabbing at straws, then there is a small chance that the server is still alive and has blocked the ping request for security reasons — namely, to prevent hackers from finding out it exists. So, you can still proceed to the next step after running the commands below, but don’t hold your breath.

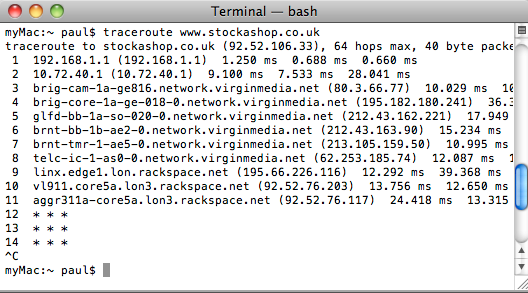

To find out if it is a networking issue, use traceroute on Mac or Linux and tracert on a PC, or use the trace option on a website such as Network-Tools.com. On Mac and Linux type:

paul@MyUbuntu:~$ traceroute www.stockashop.co.ukOn Windows:

C:> tracert www.stockashop.co.ukTraceroute traces a route across the Internet from your computer to your server, pinging each bit of networking equipment that it finds along the way. It should take 8 to 20 steps (technically known as “hops”) and then time out or show a few asterisks (*). The number of steps depends on how far away the server is and where the network has broken down.

The first couple of steps happens in your office or building (indicated by IP addresses starting with 192.68 or 10). The next few belong to your broadband provider or a big telecommunications company (you should be able to tell by the long name in front of the IP address). The last few belong to your hosting company. If your server is alive and well, then the very last step would be your server responding happily and healthily.

Traceroute on a Mac, through the broadband company and host to an unresponsive server.

Barring a major networking problem, like a city-wide power outage, traceroute will reach your hosting company. Now, you just need to determine whether only your server is ill or a whole rack or room has gone down.

You can’t tell this just from traceroute, but chances are the servers physically next to yours have similar IP addresses. So, you could vary the last number of your server’s IP address and check for any response. If your server’s IP address is 123.123.123.123, you could try:

C:> ping 123.123.123.121C:> ping 123.123.123.122C:> ping 123.123.123.124C:> ping 123.123.123.125If you discover that the server is in the middle of a range of 10 to 20 IP addresses that are all broken, then it could well indicate a wider networking issue deep within the air-conditioned, fireproof bunker that your server calls home. It is unlikely that the hosting company would leave so many IP addresses unused or that the addresses would have all crashed at the same time for different reasons. It is likely, though not definitive, that a whole rack or room has been disconnected or lost power… or burned down.

Alternatively, if nearby IP addresses do reply, then only your server is down. You can proceed to the next step anyway and hope that the cause is that your server is very secure and is blocking ping requests. Perhaps upgrade that deep frown to a pronounced grimace.

Otherwise, you’ll have to keep listening to Foreigner until your hosting company answers the phone. It is the only one that can fix the network and/or restart the server. But at least you now have someone else to blame. And if you are number 126 in the queue, it’s probably because 125 other companies think their websites have suddenly gone down, too.

4. Check Your Web Server Software

If the server is alive but just not serving up websites, then you can make one more check before logging onto the server. Just as your office computer has a lot of software for performing various tasks (Photoshop, Firefox, Mac Mail, Microsoft Excel, etc.), so does your server. Arguably its most important bit of software is the Web server, which is usually Apache on Linux servers and IIS on Windows servers. (From here on in, I will refer to it as “Web server software,” because “Web server” is sometimes used to refer — confusingly — to the entire server.)

When you visit a website, your Web browser communicates with the Web server software behind the scenes, sharing caching information, sending and receiving cookies, encrypting and decrypting, unzipping and generally managing your browsing experience.

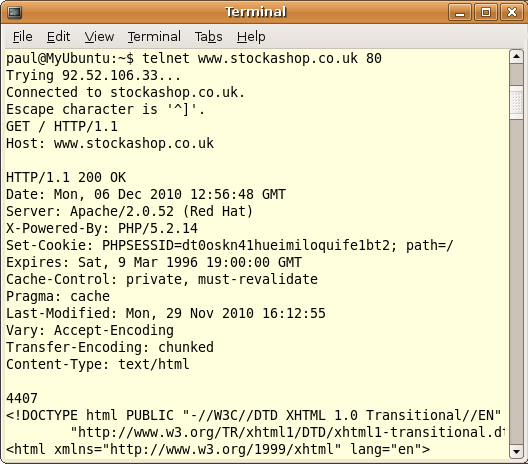

You can bypass all of this and talk directly to the Web server software by using the telnet command, available on Windows, Linux and Mac. It will tell you conclusively whether your Web server software is alive. The command ends with the port, which is almost always 80:

ping@MyUbuntu:~$ telnet www.stockashop.co.uk 80

If all were well, then your Web server software would respond with a couple of lines indicating that it is connected and then wait for you to tell it what to do. Type something like this, followed by two blank lines:

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: www.stockashop.co.uk

The first / tells it to get your home page; you could also say GET /products/index.html or something similar. The Host line tells it which website to return, because your server might hold many different websites. If your website were working, then your Web server software would reply with some headers (expiry, cookies, cache, content type, etc.) and then the HTML, like this:

Checking the web server software with telnet.

But because there is a problem, telnet will either not connect (indicating that your Web server software has crashed) or not respond (indicating that it is misconfigured). Either way, you’ll need to keep reading.

5. Logging Into Your Server

The remote investigations are now over, and it’s time to get up close and personal with your errant server.

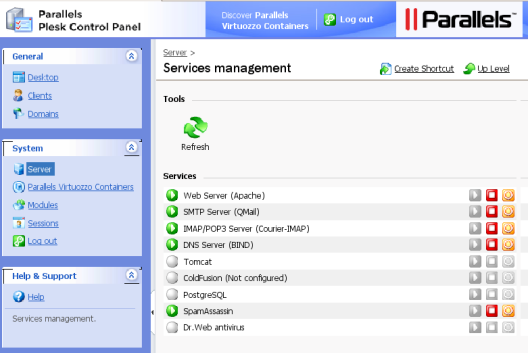

First, check your server’s documentation to see whether the server has a control panel, such as Plesk or cPanel. If you’re lucky, it will still be working and will tell you what is wrong and offer to restart it for you (in Plesk, click Server → Service Management).

If your server has a control panel such as Plesk, try logging in to make sure the Web server is running.

If not, then the following commands apply to dedicated Linux servers. You could try them in shared hosting environments, but they probably won’t work. Windows servers are a different kettle of fish and won’t be addressed in this article.

To log in and run commands on the server, you will need the administrative user name and password and the root password, as provided by your host. For shared hosting environments, an FTP user name and password might work.

On Linux and Mac, the command to run is ssh, which stands for “secure shell” and which allows you to securely connect to and run commands on your server. You will need to add your administrative user name to the command after -l, which stands for “login”:

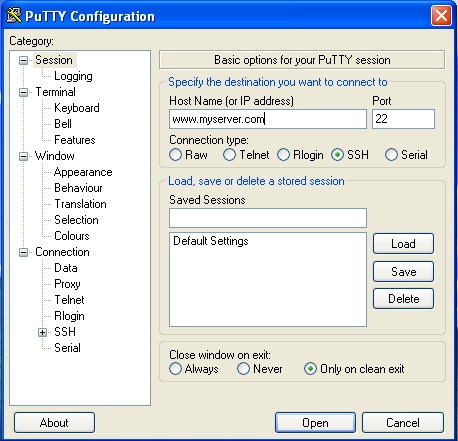

paul@MyUbuntu:~$ ssh -l admin www.stockashop.co.ukWindows doesn’t come with ssh, but you can easily download a Windows SSH client such as Putty. Download putty.exe, save it somewhere and run it. Type your website as the host name and click “Open.” It will ask you who to log in as and then ask for your password.

Using Putty to SSH from a Windows computer.

Once you have successfully logged in, you should see something like admin@server$, followed by a flashing or solid cursor. This is the Linux command line, very similar to the Terminal or command prompt used above, except now you are actually on the server; you are a virtual you, floating around in the hard drive of your troubled server.

If ssh didn’t even connect, then it might be blocked by a firewall or turned off on the server. If it said Permission denied, then you’ve probably mistyped the user name or password. If it immediately said Connection to www.stockashop.co.uk closed, then you are trying to log in with a user name that is not allowed to run commands; make sure you’re logging in as the administrative user and not an FTP user.

6. Has It Run Out Of Space?

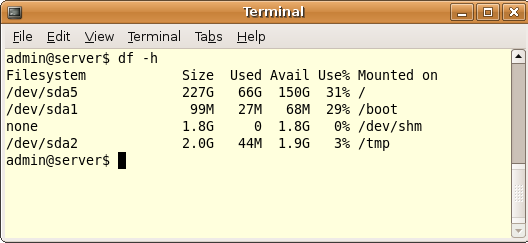

Your server has likely not run out of hard disk space, but I’m putting this first because it’s a fairly easy problem to deal with. The command is df, but you can add -h to show the results in megabytes and gigabytes. Type this on the command line:

admin@server$ df -hThe results will list each file system (i.e. hard drive or partition) and show the percentage of each that has been used.

Checking hard disk usage on a Linux server.

If any of them show 100% usage, then the command probably took eons to type, and you will need to free up some space fast.

Quick Fix

You should still be able to FTP to the server and remove massive files that way. A good place to start is the log files and any back-up directories you have.

You could also try running the find command to search for and remove huge files. This command finds files bigger than 10 MB and lets you scroll through the results one page at a time. You might need to run it as root to avoid a lot of permission denied messages (see below for how to do this). It might also take a long time to run.

root@server# find / -size +10000000c | moreYou could also restrict the search to the full partition or to just your websites, if you know where they are:

root@server# find /var/www/vhosts/ -size +10000000c | moreIf you want to know just how big those files are, you can add a formatting sequence to the command:

root@server# find /var/www/vhosts -size +10000000c -printf "%15s %pn"When you’ve found an unnecessarily big file, you can remove it with rm:

root@server# rm /var/www/vhosts/badwebsite.com/backups/really-big-and-old-backup-file.tgzPermanent Fix

Clearing out back-ups, old websites and log files will free up a lot of space. You should also identify any scripts and programs that are creating large back-up files. You could ask your host for another hard drive.

7. Has It Run Out Of Memory?

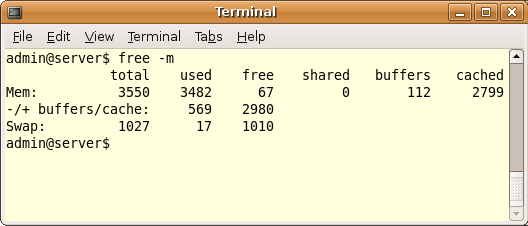

Your server might just be running really, really slowly. The free command will let you know how much memory it is using. Add -m to show the results in megabytes.

admin@server$ free -mThe results will show how much of your memory is in use.

Checking memory usage on a Linux server.

The results above say that the server has 3550 MB, or 3.5 GB, of total memory. Linux likes to use as much as possible, so the 67 MB free is not a problem. Focus on the buffers/cache line instead. If most of this is used, then your server may have run out of workable memory, especially if the swap space (a bit of the hard drive that the server uses for extra memory) is full, too.

If your server has run out of memory, then the top command will identify which bit of software is being greedy.

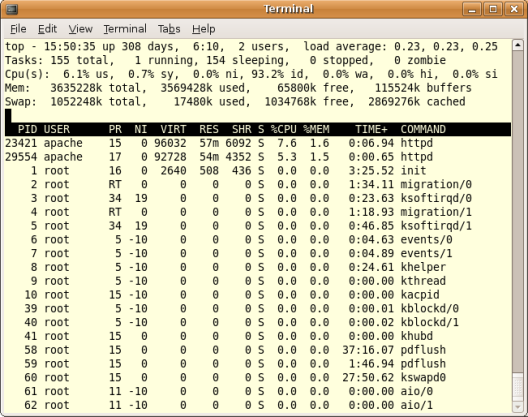

admin@server$ topEvery few seconds, this gives a snapshot of which bits of software are running, which user started them and how much of your memory and CPU each is using. Unfortunately, this will run very slowly if memory is low. You can press “Q” or Control + C to exit the command.

The Linux top command shows what is running.

Each of the bits of software above is known as a “process.” Big pieces of software such as Apache and MySQL will often have a parent process with a lot of child processes and so could appear more than once in the list. In this benign example, a child process of the Apache Web server is currently the greediest software, using 7.6% of the CPU and 1.6% of the memory. The view will refresh every three seconds. Check the Mem column to see whether anything is consistently eating up a large portion of the memory.

Quick Fix

The quickest solution is to kill the memory hog. You will need to be root to do this (unless the process is owned by you — see below). First of all, though, search on Google to find out what exactly you are about to kill. If you kill a core program (such as the SSH server), you’ll be back to telephone support. If you kill your biggest client’s data amalgamation program, which has been running for four days and is just about to finish, then the client could get annoyed, despite your effort to sweeten it with “But your website is okay now!”

If the culprit is HTTPD or Apache or MySQLd, then skip to the next section, because those can be restarted more gracefully. In fact, most things can be restarted more gracefully, but this is a quick ignore-the-consequences type of fix.

Find the process ID in the PID column of the command above, and type kill -9, followed by the number. For example:

root@server# kill -9 23421The -9 tells it to stop completely and absolutely. You can now run top again to see whether it has made a difference. If some other similar process has jumped to the memory-eating position instead, then you’ve probably only stopped a child process, and you will need to find the parent process that spawned all the greedy children in the first place, because stopping the parent will stop all the children, too. Use the process ID again in this command:

root@server# ps -o ppid,user,command 23421This asks Linux to show you the parent process ID, user and command for the process number 23421. The results will look like this:

PPID USER COMMAND

31701 apache /usr/sbin/httpdThe PPID is the parent process ID. Now try killing this one:

root@server# kill -9 31701Run top again. Hopefully, the memory usage has now returned to normal. If the parent process ID was 0, then some other process entirely is consuming memory, so run top again.

Permanent Fix

You will probably have to restart the offending software at some point because you may have just disabled your server’s SPAM filter or something else important. If the problem was with Apache or MySQL, you might have an errant bit of memory-eating programming somewhere, or Apache, MySQL or PHP might have non-optimal memory limits. There’s a slim chance that you have been hacked and that your server is slow because it’s sending out millions of emails. Sometimes, though, a server has reached capacity and simply needs more RAM to deal with the afternoon rush.

To find out what went wrong in the first place, check the web logs and/or the log files in /var/log/. When your hosting company has finally answered the phone, you can ask it to also take a look. Figuring out what happened is important because it could well happen again, especially if it’s a security issue. If the hosting company is not responsive or convincing enough, seek other help.

8. Has Something Crashed?

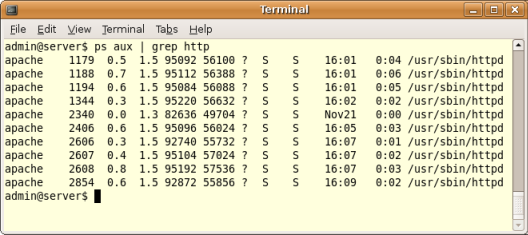

Most Linux servers use Apache for the Web server software and MySQL for the database. It is easy to see whether these are still running (and to restart them if they’re not) or are using up way too much memory. To see all processes running on your server right now, run this command:

admin@server$ ps aux | moreScroll through the list and look for signs of apache (or its older name httpd) and mysqld (the “d” stands for daemon and is related to the way the programs are run). You are looking for something like this:

USER PID %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS TTY STAT START TIME COMMAND

apache 29495 0.5 1.4 90972 53772 ? S 14:00 0:02 /usr/sbin/httpd

apache 29683 0.3 1.4 88644 52420 ? S 14:03 0:00 /usr/sbin/httpd

apache 29737 0.3 1.4 88640 52520 ? S 14:04 0:00 /usr/sbin/httpdOr you can use the grep command to filter results:

admin@server$ ps aux | grep httpadmin@server$ ps aux | grep mysqlIf either Apache or MySQL is not running, then this is the source of the problem.

This listing shows that Apache is indeed running.

Quick Fix

If Apache or MySQL is not running, then you’ll need to run the commands below as root (see below). Linux usually has a set of scripts for stopping and starting its major bits of software. You first need to find these scripts. Use the ls command to check the couple of places where these scripts usually are:

root@server# ls /etc/init.d/If the results include a lot of impressive-looking words like crond, httpd, mailman, mysqld and xinetd, then you’ve found the place. If not, try somewhere else:

root@server# ls /etc/rc.d/init.d/Or use find to look for them:

root@server# find /etc -name mysqldOnce it is located, you can run a command to restart the software. Note that the scripts might have slightly different names, like apache, apache2 or mysql.

root@server# /etc/init.d/httpd restartroot@server# /etc/init.d/mysqld restartHopefully, it will say something like Stopping… Starting… Started. Your websites will start behaving normally again!

Permanent Fix

As above, check the log files, especially the Apache error logs. Sometimes these are all in one place, but usually each website on the server has its own error log. You could look through the ones that were busiest around the time of the crash. Or else you could have a misconfiguration or a programming bug or security breach, so it could well happen again until you identify and address the cause.

Becoming a Super-User

Most of the fixes above require special permissions. For example, you (i.e. the user you have logged in as) will be able to kill or restart processes only if you started them. This can happen on shared servers but is unlikely on dedicated servers, where you will see a lot of permission denied messages. So, to run those commands, you will need to become the server’s super-user, usually known as “root.” I’ve left this for last because it’s dangerous. You can do a lot of irreversible damage as root. Please don’t remove or restart anything unless you’re sure about it, and don’t leave your computer unattended.

There are two ways to run a command as root. You can prefix each command with sudo, or you can become root once and for all by typing su. Different servers place different restrictions on these commands, but one of them should work. The sudo command is more restrictive when it turns you into a lesser non-root super-user who is able to run some commands but not others. Both commands will ask for an extra password.

For example:

admin@server$ sudo /etc/init.d/httpd restartWhen you run su successfully, the prompt will change from a $ to a #, like this:

admin@server$ suPassword:admin@server#It might say admin@server or root@server. Either way, the # means that you are powerful and dangerous — and that you assume full liability for your actions.

Conclusion

This article has provided a few tips for recognizing and solving some of the most common causes of a website going down. The commands require some technical knowledge — or at least courage — but are hopefully not too daunting. However, they cover only a small subset of all the things that can go wrong with a website. You will have to rely on your hosting company if it is a networking issue, hardware malfunction or more complicated software problem.

Personally, I don’t mind the ’80s music that plays while I’m on hold with my hosting company. It’s better than complete silence or a marketing message. But it would be even better if the support rep picked up the phone within a few seconds and was ready to help. That is ultimately the difference between paying $40 per month for a dedicated server versus $400.

When the dust has settled, this might be a conversation worth having with your boss — the one still sitting glumly by the phone, eyeing your frown, and waiting for Bono to stop warbling.

Further Reading on SmashingMag:

- Obscure Back-End Techniques And Terminal Secrets

- How to find out why your website stopped working

- 9 Steps To A Happy Relationship With Your Hosting Provider

- Effective Maintenance Pages: Examples and Best Practices

Register for free to attend Axe-con

Register for free to attend Axe-con Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

Register Free Now

Register Free Now