In Search Of The Best CAPTCHA

CAPTCHAs, or Completely Automated Public Turing Tests to Tell Computers and Humans Apart, exist to ensure that user input has not been generated by a computer. These peculiar puzzles are commonly used on the web to protect registration and comment forms from spam. To be honest, I have mixed feelings about CAPTCHAs. They have annoyed me on many occasions, but I’ve also implemented them as quick fixes on websites.

This article follows the search for the perfect solution to the problem of increasing amounts of human-generated spam. We’ll look at how and why CAPTCHAs are used and their effect on usability in order to answer key questions: what is the best CAPTCHA, and are they even desirable?

Further Reading on SmashingMag:

- Web Form Validation: Best Practices and Tutorials

- Stop Wasting Users’ Time

- Innovative Techniques To Simplify Sign-Ups And Log-Ins

The Incentive To Act Human

To understand the need for CAPTCHAs, we should understand spammers’ incentives for creating and using automated input systems. For the sake of this article, we’ll think of spam as of any unwarranted interaction or input on a website, whether malicious or for the benefit of the spammer (and that differ from the purpose of the website). Incentives to spam include:

- Advertising on a massive scale;

- Manipulating online voting systems;

- Destabilizing a critical human equilibrium (i.e. creating an unfair advantage);

- Vandalizing or destroying the integrity of a website;

- Creating unnatural, unethical links to boost search engine rankings;

- Accessing private information;

- Spreading malicious code.

All of these incentives lead to profitable or otherwise gainful situations for spammers. Automating the process obviously allows for superhuman speed and efficiency.

Those who run websites know that this is a big business and a big problem. Akismet, the popular spam killer (commonly seen as a WordPress plug-in), catches over 18 million spam comments per day and has caught more than 20 billion in its history. Mollom, which provides a similar service, catches over half a million spam comments per day and estimates that more than 90% of all messages are spam.

No amount of asking nicely will stop the spammers, but their greed can be used against them; using automated systems to increase profit does have a weakness.

Enter the CAPTCHA

On one side of the coin is the spammer; on the other is the humble website owner, a pleasant sort, who experiences common problems:

- Blogs and forums that sink under the weight of spam posts,

- Accounts that are registered under false pretences for unlawful purposes,

- Bots that ruin the dynamics of a website,

- A dive in the quality of content and the user experience.

Automated spam plagues website owners to no end, so CAPTCHAs are appealing and compelling… initially. The time needed to moderate and review user-generated content versus the time needed to implement a CAPTCHA is what pushes most developers to do it.

In fact, CAPTCHAs are used a lot. The reCAPTCHA project estimates that over 200 million reCAPTCHAs are completed daily, and it takes an average of 10 seconds to complete one. The Drupal CAPTCHA project logs close to 100 thousand uses per week, and this is just a fraction of websites (those that choose to report back).

CAPTCHAs tackle a problem head-on: they focus purely on stopping spammers. Genuine users are, for the most part, overlooked. That is to say, an assumption is made that the normal behavior of users is not affected.

It’s not true, though. The issue of genuine usability is not new. The W3C released a report back in 2005 on the inaccessibility of CAPTCHAs, which suggested that some systems can be defeated with up to 90% accuracy. More recently (in 2009), Casey Henry looked at the effectiveness of CAPTCHAs on conversion rates and suggested a possible conversion loss of around 3%:

“Given the fact that many clients count on conversions to make money, not receiving 3.2% of those conversions could put a dent in sales. Personally, I would rather sort through a few spam conversions instead of losing out on possible income.”— Casey Henry, CAPTCHAs’ Effect on Conversion Rates

In 2010, a team from Stanford University released a report entitled “How Good Are Humans at Solving CAPTCHAs? A Large Scale Evaluation” (PDF), which evaluates CAPTCHAs on the Internet’s biggest websites. Unsurprisingly, the results weren’t favourable, the most astounding being an average of 28.4 seconds to complete audio CAPTCHAs. The study also highlighted worrisome issues for non-native English speakers.

Web developers like Tim Kadlec have called for death to CAPTCHAs, and he makes a strong argument against their use:

“Spam is not the user’s problem; it is the problem of the business that is providing the website. It is arrogant and lazy to try and push the problem onto a website’s visitors.”— Tim Kadlec, Death To CAPTCHAs

Completing a CAPTCHA may seem like a trivial task, but studies (like that of the W3C) have shown that that’s far from the reality. And as Kadlec mentions later in his article, what about users with visual impairments, dyslexia and other special needs? Providing an inaccessible wall doesn’t seem fair. Users are the ones who invest in and give purpose to websites.

The question is, are CAPTCHAs so unusable that they shouldn’t be used at all? Perhaps more importantly, does a usable CAPTCHA that cannot be cracked exist? If the answer is no, what is the real solution to online spam?

The World Of CAPTCHAs

The human brain is an amazing piece of work. Its ability to conceptualize, to find order in chaos and to adapt under extraordinary circumstances makes it highly useful, to say the least. For some tasks, it outshines a computer with great ease. In other tasks — mathematics, for example — it is laughably inferior.

Logic would dictate, therefore, that the most successful CAPTCHA would be:

- A task that users excel at naturally but that computers can’t begin to comprehend,

- A task that is incredibly quick for users to perform but arduous for computers,

- A task that minimizes the need for additional user input,

- A task that is relatively accessible to all users, even those with special needs (that is, the CAPTCHA should be no more difficult than general web usage and the current task demand).

One of the greatest advantages that humans have over machines is our ability to visually recognize patterns. The most popular CAPTCHA technique derives from this.

Web developers have explored many options: simple recognition tests, interactive tasks, games of Tic Tac Toe and equations that even mathematicians would have struggled with. We’ll explore the more sensible ideas being implemented online today.

Text Recognition

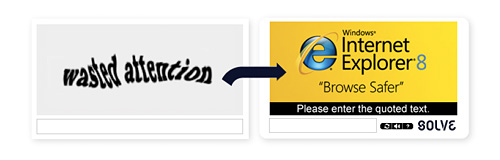

The most popular type of CAPTCHA currently used is text recognition (as seen with the reCAPTCHA project).

The reCAPTCHA project aims to stop spam and help digitize books.

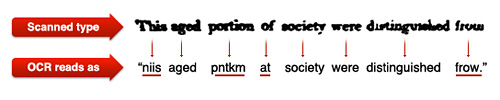

reCAPTCHA was created at Carnegie Mellon University, home to the CAPTCHA pioneers and (in 2000) coiners of the term. Now run by Google, the project uses scanned text that optical character recognition (OCR) technology has failed to interpret. This, in theory, provides unbreakable CAPTCHAs, with the secondary benefit of helping to digitize books.

reCAPTCHA’s example of failed OCR scanning.

Concerns of accessibility and usability are often voiced with regard to this type of CAPTCHA. Completely illegible CAPTCHAs are common on the Web, and asking users to perform impossible tasks can not be good for usability.

The reCAPTCHA project does make efforts to provide audio alternatives for visually impaired users, but many more text-recognition CAPTCHAs are being used without aids. As noted in the Stanford University study, audio CAPTCHAs take a long time to complete. The same study also highlighted an undesirable reliance on recognition of English-language words.

Another take on the basic text CAPTCHA was introduced in late 2010 by Solve Media, whose solution was to replace text with an advertisement and a related question, a move that many saw as too invasive.

Solve Media claims its CAPTCHAs can be solved more quickly than others. While we should be skeptical of marketing talk, there is clearly some potential, given that many global brands transcend a single language. There is potential here for marginal improvement.

While text-recognition CAPTCHAs have a few downsides (e.g. spammers could use a software that would be able to recognize text embedded in the image and try all possible combinations to “break” the anti-spam mechanism), they are undoubtedly recognizable. This fact alone can go a long way in usability decisions.

Logic Questions

Some have suggested that answering simple logic questions would be better than performing visual tasks, the idea being that the complexity of written language would be enough to confuse computers.

The TextCAPTCHA service has over 180 million questions in its database, including:

- The 6th letter in “unrolled” is?

- What is fifty-eight thousand, five hundred and seventy-four as digits?

- Which of 3, twenty-nine, 70, 46 or 65 is the lowest?

These CAPTCHA questions are designed for the intelligence of a seven-year-old child. They are far more accessible than text and image recognition, and while this is a big advantage, it comes with a price. First, the time required to read and comprehend these questions will vary because they are unusual and unknown to users. Secondly, computers can still break these CAPTCHAs. Joel Vanhorn points to Wolfram Alpha as an intelligence source strong enough to crack them.

With the likes of IBM’s Watson recently showcasing an eerily human-like ability to process language, such technology might become mainstream quicker than we think. Instead of worrying about logic questions becoming solvable by computers, we should use this technology to analyze user-submitted content and then separate natural language from the computer-generated content that is common to spam. Services like SBlam! are implementing this idea.

Questions that are website-specific, such as “What is the name of this website?” and “What is the dominant color in the image above?”, might be better than general questions. The downside, of course, is that the pool of pointed questions is very small compared to the 180 million possibilities of TextCAPTCHA.

The biggest problem with logic questions is that they’re specific to a language, usually English. Providing millions of questions in every language in order to avoid alienating potential users would be a huge task. When presented with such a daunting prospect, the same question resurfaces: are CAPTCHAs the right solution?

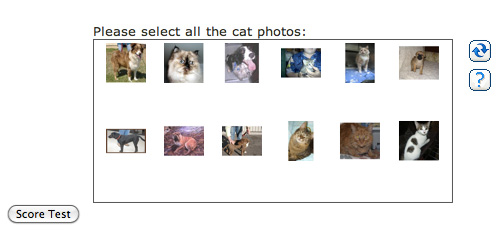

Image Recognition

Many have experimented with photography instead of text. The benefit? No legibility issues. Services like identiPIC ask users to identify the object in an image. Microsoft has also researched this method through its Asirra project.

Microsoft’s Asirra project on image recognition.

The fact that we haven’t seen widespread adoption of image recognition CAPTCHAs indicates that it doesn’t improve usability. In fact, it jeopardizes accessibility. Visually impaired users have no chance of passing this type of CAPTCHA, and including a description or alternative text would weaken the tests.

In 2009, Google published research (by a team led by Rich Gossweiler, Maryam Kamvar and Shumeet Baluja) that looked at an alternative form of image CAPTCHA. The project asked users to correct the orientation of images by rotating them.

A novel idea, I’m sure you’ll agree, and the research showed a preference for the ease and simplicity of this technique. Sadly, it fails the accessibility requirement (think again of the visually impaired).

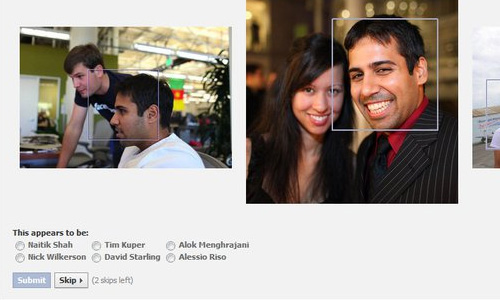

Friend Recognition

One of the more interesting CAPTCHA ideas appeared in January 2011 as a result of an effort by social-networking giant Facebook. The company is currently experimenting with social authentication in an effort to verify account authenticity. In the words of the experiment:

“We will show you a few pictures of your friends and ask you to name the person in those photos. Hackers halfway across the world might know your password, but they don’t know who your friends are.”— Alex Rice, Facebook, A Continued Commitment to Security

A peek at Facebook’s friend recognition test.

What makes Facebook’s project slightly different than the normal CAPTCHA is that the authentication is supposed to filter out human hackers rather than machines.

There is potential for Facebook to roll this out across the web. With 600 million users and millions of websites that integrate with it, Facebook has the ability to use this social recognition CAPTCHA in a big way — and it could prove to be easier than text recognition (Orwellian privacy concerns aside for the moment).

There is one problem. Do you actually know who your friends are? The reality is that friend requests are exchanged between even the barest of acquaintances; remembering names to go with all those faces could be challenging. As intuitive and intelligent as Facebook’s idea might be, it is ultimately flawed because, as humans, we don’t follow the rules.

User Interaction

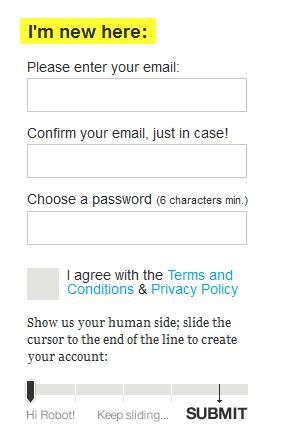

One method getting a lot of attention has users perform tasks that are impossible for virtual intelligence. They Make Apps features a small slider that must be dragged to the right in order to submit a form. It asks the visitor to “Show your human side; slide the cursor to the end of the line to create your account.”

They Make Apps uses a slider CAPTCHA.

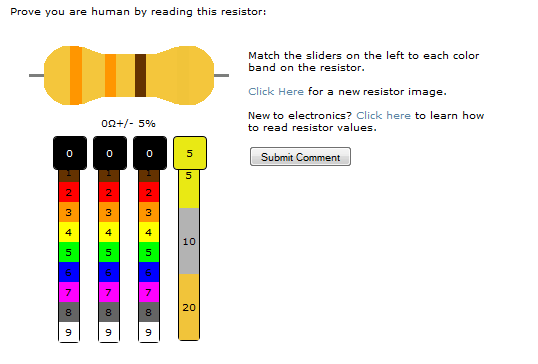

Obviously this option is inaccessible to people with special needs. Furthermore, developing a script that is capable of moving the slider automatically to activate the “Submit” button would probably be not that difficult. A multilateral version of the slider option is used in the comments section of the Adafruit blog. Four different sliders have to be matched to the corresponding colors in order to validate a comment and activate submission.

The Adafruit blog’s slider CAPTCHA.

An Over-Engineered Solution?

None of the solutions above meet all of the requirements we highlighted for a perfect CAPTCHA. Each of them impairs usability for a large segment of potential users. Even if we went so far as to assume that users generally welcomed traditional text-recognition CAPTCHAs, they would not likely welcome the other alternatives. The extra few seconds the user takes to decipher what is being asked of them negates the benefits. Too slow means not worth it.

Of the solutions available, text recognition (like reCAPTCHA) still feels like the best choice. But the question remains: why are we asking users to perform these tasks? Surely we can beat spammers at their own game by using automated systems to do the work for us. So far we have assumed that a common problem actually exists for CAPTCHAs to solve.

Despite the advances in intelligent computer systems, most spamming mechanisms are stupid. If a submission fails (because of the CAPTCHA or some other reason), the spam bot will move down its list of thousands of websites. Jeff Atwood showed this in his 2006 article “CAPTCHA Effectiveness.” Despite all the research that goes into CAPTCHA-breaking, most spammers have no incentive to invest effort in defeating them. The sheer quantity of websites available to attack and the speed at which they can do it means that CAPTCHA-breaking is unlikely to concern many spammers.

The BBC is one of the most highly scrutinized institutions in the UK. Its requirements for accessibility are second to none, and its recent examination of CAPTCHAs resulted in an emphatic “No”:

“Visually impaired participants expected full accessibility from the BBC and we felt it would affect our reputation to use them. Elderly users had issues with the distorted text. The logic puzzles were found to be odd and patronising. The audio was struggled with. Overall, extremely negative feelings were expressed towards CAPTCHA technology.”— Rowun Giles, BBC, CAPTCHA and BBC iD

Alternative solutions exist that prevent automated submissions without resorting to CAPTCHAs and, more importantly, without user interference.

Alternatives To The CAPTCHA

CAPTCHAs, in their purest form, might realize their potential in another field. As website protectors, though, they’re far from ideal. Doing a disservice to users in an effort to combat spam doesn’t cut it on today’s web. Human-powered spam is on the rise (as is unethical link-building), and we should be implementing unobtrusive, invisible methods.

Automated and Manual Spam Detection

We touched on two detection services at the beginning of this article. Akismet, Mollom and SBlam! all analyze user-submitted data and flag spam automatically. Mollom sometimes presents a CAPTCHA, but only when it’s unsure. But why not develop your own system that is tuned to the mechanics of your website?

Taking responsibility and removing the burden from users will improve their interactions with and impressions of your website. Manually moderating content is often a sacrifice worth making.

The Honeypot Method

In 2007, Phil Haack suggested a clever method of detecting bots: using a honeypot. The idea behind the honeypot method is simple: website forms would include an additional field that is hidden to users. Spam robots process and interact with raw HTML rather than render the source code and therefore would not detect that the field is hidden. If data is inserted into this “honeypot,” the website administrator could be certain that it was not done by a genuine user.

The honeypot method can be made more sophisticated by using JavaScript and data hashing. These obfuscation methods are not hack-proof, but we can assume that robots are not sophisticated enough to enter the required information.

JavaScript can be used to fill in hidden fields dynamically, which server-side validation can check for. Scratchmedia provides an example of this hidden field solution, along with an alternative CAPTCHA if JavaScript is disabled.

Additional timestamp and session data checks can also be used to detect automated submissions. A recent discussion on Stack Overflow provides many examples and ideas about this, including the implementation of Hashcash, which is available as a WordPress plug-in. A jQuery tutorial explains a similar method and includes an interesting thought:

“Thieves know to look for stickers, dogs in the yard, lights on the exterior of a home, and other signs of a well-guarded house. They’re looking for high payoff with minimal work and risk.”— Jack Born, Safer Contact Forms Without CAPTCHAs

The analogy suggests that, as with CAPTCHAs, the method used does not stop intruders so much as the presence of any hurdle at all. As mentioned, spammers currently have too many targets to bother searching for a back door.

Centralizing the User Base

With the rise of the social web, many websites now allow users to register and interact with one another. Publishing to a third-party website was traditionally done either by registering a full-fledged account or by submitting totally anonymously, both of which methods leave the gate open to spam. In 2008, Facebook announced Facebook Connect, which provides websites and their users with an integrated platform that addresses this and other concerns. Twitter followed suit in 2009 with a similar service (“Sign in with Twitter”). Both of these services can be implemented on websites relatively easily, and they eliminate the need for registration and comment forms, which are accessible to robots.

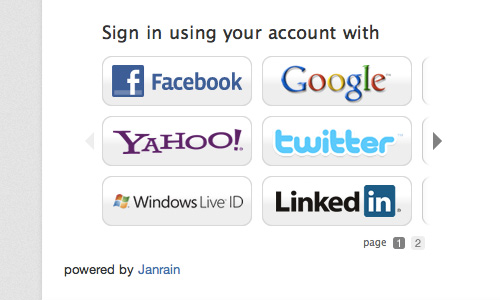

So many websites offer social-networking integration that services like Janrain have popped up. Janrain provides an abstracted umbrella solution to ensure that websites are accessible through any account platform.

Mahalo provides social log-in functionality via Janrain.

Mahalo provides social log-in functionality via Janrain.

Other services, such as the commenting platform Disqus, allow user interaction with built-in spam detection and user sign-in.

Less anonymity and more accountability make users think twice about the content they submit. It also enables human spammers to be detected and banned quickly across entire websites; remove one Facebook profile and the whole Facebook Connect network is safe from that account owner’s dastardly deeds.

Such services, of course, provoke heated debates about privacy, data protection and the like… but that’s for another article. As alternatives for preventing spam without CAPTCHAs while maintaining usability and accessibility, they have great potential.

Recording User Time Expenditure

Another rather simple method that can be implemented without annoying users is to distinguish between users and bots by measuring the time they take to fill out a contact form or compose a comment. By estimating the average time spent on a comment, one could define certain rules. For example, if a submission takes less than five seconds, which is virtually impossible for a human but just enough time for a bot to do its job, you could ask the user to try again. Jack Born’s tutorial on a slight variation of this concept for jQuery is worth a peek, since most users have JavaScript enabled. The whole endeavor is based on one crucial assumption: spammers prefer going after the easiest targets and will leave a website untouched if their initial attempt fails (although this can never be guaranteed).

The Perfect CAPTCHA

It would seem evident from years of use and research that CAPTCHAs are far from perfect as a solution. Remove spammers from the equation and we remove the need for CAPTCHAs entirely; this is the mentality we should be aiming for. The perfect CAPTCHA is no CAPTCHA at all.

The Rise of Humans

CAPTCHAs, by nature, function more by blocking spam than by detecting humans (which is their purpose). But they can’t do that when the spammer is not a computer. A better solution would be to remove the incentive to spam altogether. If we can reverse the trend and drive spam from being highly lucrative to being a net loss, then both automated and manual spam will become worthless.

One of the many dark arts of search engine optimization (SEO) is to artificially generate links to the website being “optimized.” Search engines consider inbound links a strong indicator of value. This can be abused, obviously, by posting worthless links on many websites (forums and comment forms are perfect for this). The SEO benefits are so worthwhile that automated spamming isn’t even required. The practice of enlisting cheap human labor is emerging. And CAPTCHAs are not designed to stop this.

We should accept the need for moderation and background detection. CAPTCHAs are a stop-gap solution at best, and are lazy and inaccessible at worst. Whether you choose to fight the good fight or simply put the interests of genuine users first, you have options.

Taking a Stand

If website owners work together to eliminate the incentives to spam, then spam will slowly wear away over time and eventually remove the need for CAPTCHAs. Is that too idealistic? Probably. In reality, we are likely to see a combination of technology and law dealing the death blow to spammers.

Google’s latest algorithm change has significantly demoted low-quality content farms (the effects of which are explained by Johannes Beus). Advances such as this will ultimately remove all incentives to game the system. However, if we website owners don’t evangelize and adopt alternative solutions, then we might just wake up to a world where CAPTCHAs are worthless and our websites are unmanageable.

Understanding the alternatives (whereby spam detection is silent to users) and implementing them on our clients’ websites is a good start. It’s a positive step toward usability and conversion rates (and clients will love that!). If users comment on your website, reward them with a simple experience. This can be done in several ways:

- Moderation wherever possible. Disallow certain content to be posted directly to your website, or allow it through maintained and verified account management. Better yet, use a service like Facebook Connect or Disqus; you’ll make things easier for both yourself and users.

- CAPTCHA alternatives. Try the honeypot method or another that is invisible to users. Some could potentially be bypassed, but their presence is often enough to thwart automated efforts.

- Client-side detection. This can work because, while there are simple workarounds, spammers won’t waste time (for now). Keyword and mouse interactions can be used to detect genuine user input. This option shouldn’t be used on its own but can add extra assurance.

- Server-side spam detection. Developers should focus on server-side spam detection that monitors users and flags unusual activity. Specialist services like Akismet are affordable and proven, but bespoke systems can be tailored to the nuances of your website.

- Social moderation. Move toward more sophisticated features that allow this. The simple act of voting content up and down can help to push spam away or flag it for deletion.

It seems clear, considering all the pros and cons of CAPTCHA, that the future lies in a system that is invisible to normal web use. For now, using a CAPTCHA should be your last resort.

Do you use CAPTCHAs in your designs? If yes, which ones?

Further Reading

- History of the CAPTCHA A brief history of how CAPTCHAs emerged on the web.

- Inaccessibility of CAPTCHA The W3C’s 2005 study on CAPTCHA usage and accessible alternatives.

- CAPTCHAs’ Effect on Conversion Rates Casey Henry’s 2009 study (from the SEOmoz blog) on CAPTCHAs and their effect on conversions.

- How Good Are Humans at Solving CAPTCHAs? A Large Scale Evaluation A Stanford University study, researched by Elie Bursztein, Steven Bethard, Celine Fabry, John C. Mitchell and Dan Jurafsk.

- CAPTCHA Is Dead, Long Live CAPTCHA! A review of the state of CAPTCHAs in 2008 by Jeff Atwood.

- The State of Web Spam: Human-Posted Spam Is on the Rise A ReadWriteWeb article by Frederic Lardinois.

- How do you stop scripters from slamming your website hundreds of times a second? A discussion at Stack Overflow that suggests many alternative solutions.

We express sincere gratitude to our Twitter followers and Facebook fans for their support and feedback in helping to prepare this article.

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

Register Free Now

Register Free Now

Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers