Introduction To DNS: Explaining The Dreaded DNS Delay

Imagine that your biggest client calls because they are having trouble retrieving their email. Or they want to know what their best-selling item is right now. Or their most popular blog post. Perhaps their website has suddenly gone down. You can hardly reply, “No problem, I’ll get back to you in 24 to 48 hours.”

And yet DNS gets away with it! If you need to move a website or change the way a domain’s email is handled, you’ll be faced with a vague 24 to 48-hour delay. This is quite an anomaly in a world of ultra-convenience and super-fast everything. This article explains what DNS is, how it works, where that pesky delay comes from, and a couple of ways to work around it.

What Is DNS?

DNS is the “domain name system.” It translates human-friendly website addresses like www.cnn.com157.166.224.25. Try visiting https://157.166.224.25 if you’d like to verify this.

Every computer, Web server and networking device on the Internet has one of these numerical IP addresses. In some cases, through a process called “network address translation,” a whole house, office or building shares the same IP address. But the addresses are otherwise unique, and they allow computers to easily route information around the Internet.

DNS is a distributed service. No single computer out there translates domain names to addresses. Instead, the task is shared by millions of name servers (also spelt as one word, “nameserver”), which constantly refer to and update each other.

Your Local Name Server

Every computer connected to the Internet has a name server. When you attempt to visit a website like www.smashingmagazine.com80.72.139.101 in this case. Your computer’s name server can’t make this translation by itself; it has to keep asking other name servers until something somewhere comes back with a definitive answer.

Your local name server is like the little address book that you kept near the telephone before mobiles were invented. If you hired A1 Triple Glazing to retrofit your windows, you might have copied their phone number into your address book. The next time you had to ring them, the number would be right there, immediately available. Or under the sofa.

Some Name Servers Are Special

The name servers just “know.” Every domain name like smashingmagazine.com has at least one name server that authoritatively and definitively knows the correct IP address. The authoritative name servers for smashingmagazine.com are flashily called a.regfish-ns.net, b.regfish-ns.net and c.regfish-ns.net.

This is like saying that A1 Triple Glazing’s phone number can definitely be found in the Northampton Yellow Pages. That particular phone book is the authoritative source of information on the whereabouts of A1 Triple Glazing.

Where The Delay Comes From

Say A1 Triple Glazing decides to change its phone number. It could take up to 12 months before the 2012 edition of the Northampton Yellow Pages comes out with the updated phone number. And it could take a further 12 to 36 months before you next go up to Northampton, check the Yellow Pages, and copy the new phone number into your personal address book. In the intervening 24 to 48 months, your address book would be out of date. And if you ever rang A1 Triple Glazing, you’d be disconnected instantly… or end up speaking to a hairdresser. Fortunately, new windows generally have a 10-year guarantee. But websites need to be a bit more responsive than that.

Creating A New Website

DNS becomes important whenever you need to create a new website or move an existing one. New websites are the simpler case, so we’ll discuss them first. With any new website, you need to do several things:

1. Buy The Domain Name

A company from which you buy and register a domain name is called a registrar. Registrars get a special license from ICANN that allows them to sell domain names. The license costs $2500 (US) to apply, plus $4000 per year. Some particularly large registrars are GoDaddy in the US and 123-reg in the UK.

After registering a new domain name, there may be a delay of a few minutes to a few hours before you can log into the registrar’s website to change the domain’s name servers (step 3 below) or point to an IP address (step 4 below). This delay is a result of the registrar processing your payment, adding you to the Whois database and updating its records. The delay applies only to brand new domains and so is not part of the DNS delay.

2. Find A Host For The Website

The hosting company puts your website on a big powerful server somewhere, provides you with an IP address and charges you monthly. Thousands of big and small companies offer hosting or resell another company’s. Most registrars also offer hosting, and if you buy the domain name and hosting space from the same company, you won’t need to worry at all about DNS.

3. Specify Name Servers For Your Domain

This step is akin to specifying which Yellow Pages your domain name should appear in. Usually you can skip this step and just use the default name servers provide by the registrar.

You might want to change them if, for example, you registered the domain names (step 1 above) with several companies but wanted to manage the DNS (step 4 below) from one place. Or perhaps you used Really Cheap Registrar Plc to register the domain names, but you want to use Really Flexible DNS Plc to manage the DNS. Or perhaps your host (step 2) has a nice DNS interface that you’d like to use.

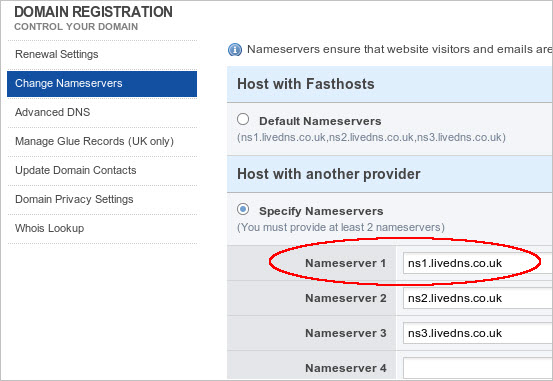

To change the name servers, log into your registrar (from step 1 above), navigate to the domain name in question, and look for a “Change name servers” option, as in the screenshot above. Really Flexible DNS Plc will tell you what to change them to.

4. Point The Domain Name At The IP Address

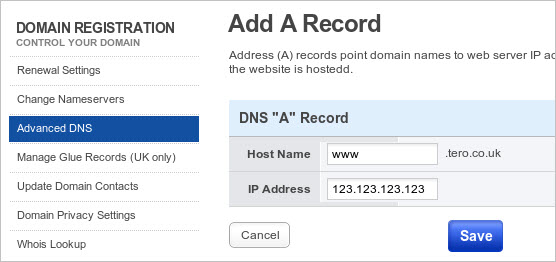

Now you need to log into whichever company is providing the name servers (either the registrar, the host or another) and point www.yournewdomainname.comwww as the host name (i.e. the prefix for the domain name) and the IP address given by your host in step 2.

You can use the same process to create other address records, such as webmail.yournewdomainname.com. Sometimes you can enter *everything.yournewdomainname.com will point to the IP address. And if you enter @ as the host name, then it will point yournewdomainname.com without any host name.

5. Wait For It to Happen

This is the cause of part of the DNS delay. Many companies will process your DNS request immediately. Others process requests only once or twice a day; so, if your company processes changes only at 4:00 am, and you request the change at 4:02 am, then you’ll need to wait almost 24 hours.

“Not only do we give you the power to change your DNS settings to whatever you like, but we make those changes instantly! Unfortunately, we can’t make the Internet as efficient as we are, and other web services may take longer to update. Your changes will go global just as soon as they catch up.”

The next section discusses how DNS works in detail, and the final section covers the main part of the DNS delay.

How DNS Works

When you visit a website in the browser or ping or FTP or telnet or do any networking operation, your computer needs to convert the (fully qualified) domain name into an IP address. This section shows how that happens, with commands so that you can try it yourself.

For the commands, you’ll need to open up the terminal on Mac or Linux or the command prompt on Windows. To do this on a Mac, go to Applications ? Utilities ? Terminal. In Ubuntu Linux, go to Applications ? Accessories ? Terminal. On Windows, go to Start ? Programs ? Accessories ? Command Prompt.

Note that in DNS, both smashingmagazine.com and www.smashingmagazine.com can be called “domain names.” But the latter, www.smashingmagazine.com

1. Ask Your Local Name Server

Let’s say you want to visit www.smashingmagazine.com

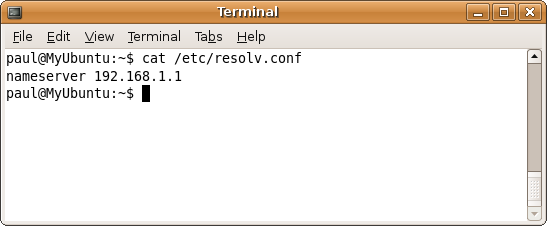

On Mac and Linux, you can run the following command to find out what your name server is:

cat /etc/resolv.conf

On Windows, the command is:

ipconfig /all

In this case, my computer sends a request to 192.168.1.1, something along the lines of, “Oi, 192.168.1.1! What’s the IP address for www.smashingmagazine.com?”

2. Your Local Name Server Doesn’t Know

Let’s say that the local domain name server, 192.168.1.1, is brand spanking new. It has never been asked anything before, let alone for the IP address of www.smashingmagazine.com

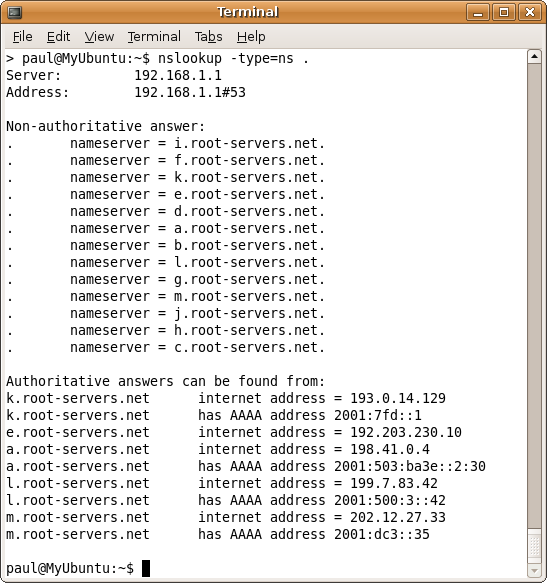

On Mac, Linux and Windows, run the command shown below. The -type=ns tells NsLookup to only return information on name servers. And the dot at the end tells it to look up root name servers.

nslookup -type=ns .This will return the names and IP addresses of a handful of root name servers. If you’d like to see what’s holding the Internet together, Wikipedia has a picture of one of these very important computers.

3. So, It Asks a Top-level Domain Name Server…

Your local name server extracts the last part of the requested domain name, which is com in this case. This is called the top-level domain or TLD. Others are net, gov, uk, fr, ie and de.

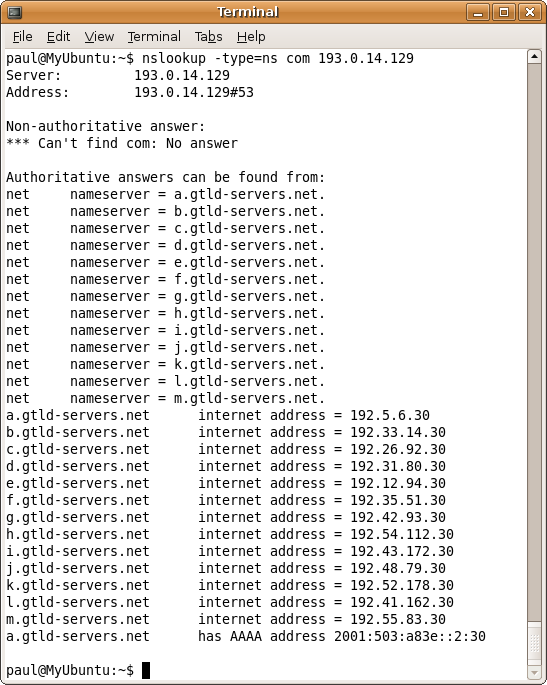

Your local domain name server picks one of the root name servers listed above and asks it something like, “Excuse me, 193.0.14.129. If you don’t mind, where would I find information about .com domains?”

You can see the sort of answer it would receive by running this command:

nslookup -type=ns com 193.0.14.129

com domains.4. … And Gets Redirected to a Lesser Domain Name Server

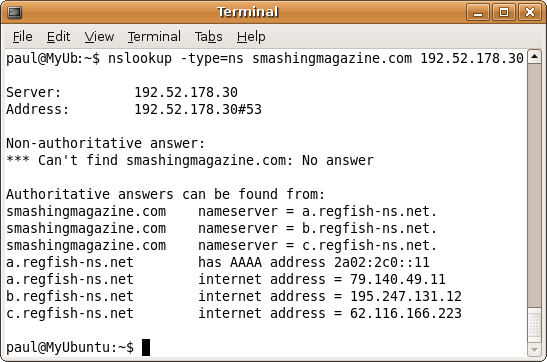

It’s nearly there. Your local name server now asks one of these TLD name servers something like, “Hi, 192.52.178.30. Do you know where I should go for stuff on smashingmagazine.com?”

You can see the answer to this question by running NsLookup again:

nslookup -type=ns smashingmagazine.com 192.52.178.30This returns a list of name servers for the domain smashingmagazine.com. The word authoritative means that these name servers are the definitive place to go for DNS information on smashingmagazine.com.

5. Get the IP Address

So, now your local name server goes to one of these name servers. It has arrived at the first part of the requested domain name, the www, so it no longer needs the name servers; it’s ready for the actual data. Now it can ask one of those name servers, “Hola, 79.140.49.11. Can you tell me the IP address of www.smashingmagazine.com? Cheers!”

Run the NsLookup command again, using the IP address of one of the domain name servers from above, but without the type=ns this time:

nslookup www.smashingmagazine.com 79.140.49.11www.smashingmagazine.com translates into 80.72.139.101.6. Remember It For Next Time

Your local domain name does not want to have to go through all that rigmarole again any time soon. So, it caches (i.e. stores) everything it has learned, including the IP addresses for TLD servers and the IP address of www.smashingmagazine.com

So, the next time you ask for a com domain, such as www.google.comwww.smashingmagazine.com

But it won’t remember that translation forever. Eventually, it will forget and have to repeat some or all of the steps above. You can use the dig command to find out how long it will remember.

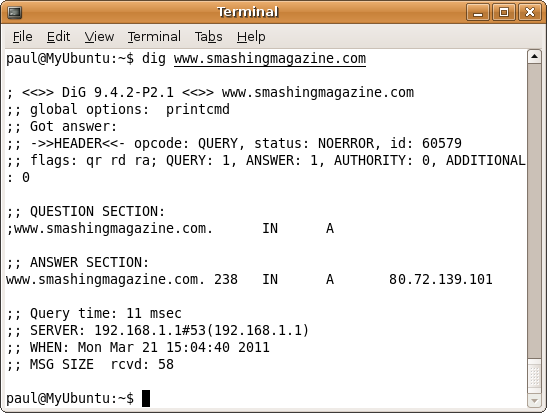

On Mac and Linux, run this:

dig www.smashingmagzine.comWindows users will need to use an online version of this tool, because Windows does not come with the dig command.

In the Answer Section, is a line starting with www.smashingmagazine.com

;; ANSWER SECTION:

www.smashingmagazine.com. 238 IN A 80.72.139.101This caching on your local name server is responsible for part of the DNS delay. In this case, even if Smashing Magazine changed its IP address right now, your computer wouldn’t know about it for at least 238 seconds, when the local name server would have to recheck its sources.

If you use the online tool, then you are not checking your personal local name server, but rather you’re checking that website’s local name server. You can run a slimmer version of this command:

dig +nocmd www.smashingmagazine.com +noall +answer

Also note that in all of the commands above, you could have provided the name of the name server rather than the IP address. NsLookup would have translated it for you.

7. Send the Answer Back to Your Computer

Finally, your local domain name server sends the answer back to you at 80.72.139.101. Your computer and/or browser might also cache this translation, so that the next time you ask for www.smashingmagazine.com

Now your computer will embark on another amazing process to communicate with the computer at the address 80.72.139.101 and ask it for a Web page. Your computer will essentially send a request down its network cable (or over its wireless connection), and ask your broadband router something like, “Can you please ask 80.72.139.101 to send me the home page for www.smashingmagazine.com?”

Your broadband router will send the same request along its network cable to the next router. This process will keep repeating. At some point, some large networking device will have several cables connected to it and will follow a rule like, “Requests for any IP addresses starting with less than 100 should go down cable #1. Everything else down cable #2,” and so on, until the request finally gets to 80.72.139.101. And the reply will be sent back in the same way.

You can follow this journey using the traceroute command on Mac and Linux and tracert on Windows:

tracert 80.72.139.101Time To Live

The caching in step six above is the main cause of the DNS delay. Any given translation (of a Web address into an IP address) has a property called “time to live” or TTL. This tells domain name servers how long they are allowed to cache the translation before having to look it up again.

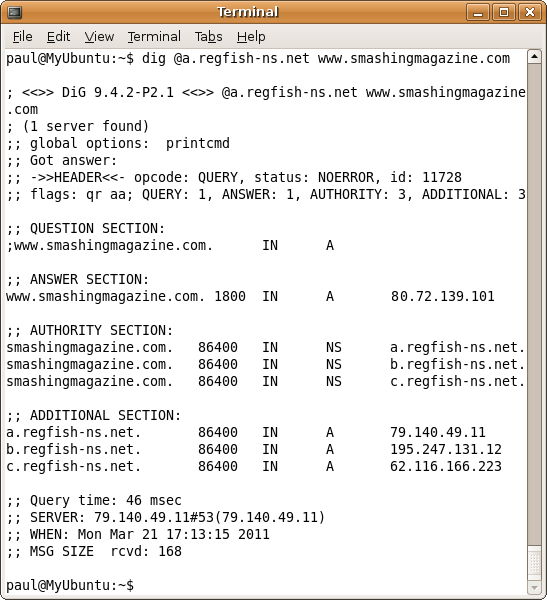

You can find out what the TTL for a given (fully qualified) domain name is using the dig command, instructing the command to use the domain name’s name server, like so:

dig @a.regfish-ns.net www.smashingmagazine.com

The Answer Section shows that www.smashingmagazine.com

;; ANSWER SECTION:

www.smashingmagazine.com. 1800 IN A 80.72.139.101That is, your local domain name server will remember this for 1800 seconds. If Smashing Magazine suddenly decided to change its IP address, your local domain name server could hang onto the old IP address for up to 30 minutes.

The command also specifies how long to remember that a.regfish-ns.net is a name server for smashingmagazine.com:

;; AUTHORITY SECTION:

smashingmagazine.com. 86400 IN NS a.regfish-ns.net.If Smashing Magazine suddenly decides to change its name servers, your local domain name server would hang onto the old name server for up to 86,400 seconds, which is one whole day. Only then would it ask for the new name server, and only then would it ask the new name server for the new translation.

Moving A Website

And now for the grand finale! This section ties together all of the above to explain the delay. Three sections ago, we had an in-depth description of how to buy a domain name and set up the DNS. This section looks at what happens when you change the IP address of an existing address.

1. Find Out the Name Servers for the Domain

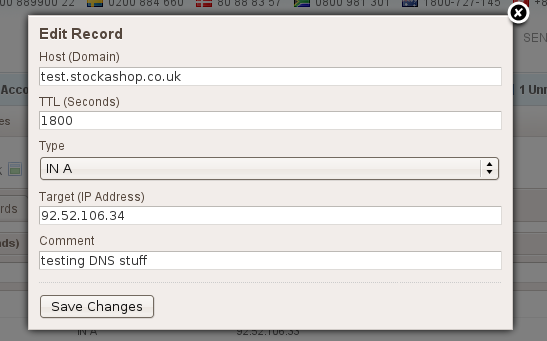

First, you need to know which name servers your domain uses. You can use the nslookup or whois command or an online networking tool. In this example, I will change the IP address of test.stockashop.co.uk.

nslookup -type=ns stockashop.co.uk

whois stockashop.co.ukThe name servers for this domain are listed as ns.rackspace.com and ns2.rackspace.com.

2. Change the IP Address

To actually make the change, you will need to log into the website of the company that manages your name servers, as in the section far above. Then find the (fully qualified) domain name that you want to move, and click on something like “Edit DNS Settings” or “Advanced DNS.” Then find the address record you want to change, and edit and save it.

3. Check Whether the Change Has Been Processed

Your DNS change will be processed after a few minutes or hours, depending on the company. To check if and when the change has been processed, you can use the nslookup command to query the name server directly. This bypasses your own local name server and gets the information straight from the horse’s mouth. You can also use an online tool, submitting the domain (test.stockashop.co.uk in this case) and server (ns.rackspace.com).

nslookup test.stockashop.co.uk ns.rackspace.comKeep running this command until it comes back with the new IP address. This particular change with Rackspace took 10 to 20 minutes. This is the first part of the DNS delay, and it could take anywhere from 0 to 24 hours.

4. Check How Long You Have to Wait

Eventually, the authoritative name servers for your domain will be changed, and it will return the new IP address. Then you can use the dig command to find out how long until your own name server reflects the change:

dig test.stockashop.co.uk

Look in the Answer Section. It will give you the IP address that it thinks is correct (ending in 33 in this case), and the number of seconds until this expires (91).

;; ANSWER SECTION:

test.stockashop.co.uk. 91 IN A 92.52.106.33After the 91 seconds have passed (which felt a lot longer than 91 seconds as I was actually doing it), the answer will suddenly change. The IP address will be the new one (ending in 34), and the number of seconds will reset back to about the time to live (1799 in this case, or 30 minutes).

;; ANSWER SECTION:

test.stockashop.co.uk. 1799 IN A 92.52.106.34Now you can restart your browser (to clear its internal cache) and visit the address. Your browser should go to the new IP address and the moved website.

You can also use an online dig to test this, although you will be using its name servers instead of your own; so even if it returns the correct IP address, you (or your client) may have to wait a bit longer.

Most DNS entries have a time to live of 86,400 seconds, which is 24 hours. This will add another 0 to 24 hours of delay, with an average of 12 hours. So, the total delay could be between 0 and 48 hours.

Note that the process is similar when changing the name servers for a domain. You can use nslookup or dig to keep track of the changes.

Minimizing The Delay When Moving A Website

There are a few techniques for shrinking the delay, or eliminating it entirely. Please comment if you have any other suggestions.

1. Make the Delay Immaterial

If the website is static and never changes, then having an exact copy on both the old and new hosts will be sufficient. Visitors won’t be able to tell whether they are seeing the old or new one. Or, if you are in a position to shut down dynamic content (such as turning off the comments on a blog for a weekend), then you can make your website static for the duration of the transfer period.

2. Update the Database Across the Internet

All big websites use a database that updates frequently based on user events, such as blog comments and items in shopping baskets. When moving this kind of website, it is possible to subject only the files (HTML, PHP, ASP, etc.) to the DNS delay, and not the data. As above, make an exact copy of the website’s files on the new host. Then configure the new host to access the database still residing on the old host (which may require some firewall configuration). Then make the DNS changes and wait out the delay. Then, at a convenient time, when few people are using the website, transfer the database.

3. Change the TTL

An alternative is to lower the time to live for the transfer. The TTL is usually set to a day to avoid a lot of unnecessary Internet traffic, and many registrars and hosting companies do not let you change the TTL. But some do, such as Rackspace (as seen above), and this alone could be the deciding factor for your choice of a DNS.

You can change the TTL from 86,400 seconds to 300 seconds (5 minutes), and then wait a day for all name servers around the world to learn about this change. Then copy the website and database across as quickly as possible, make the DNS change, and everyone should know about it within five minutes. Then change it back to 86,400 seconds. (Some hosts, like Rackspace, do this automatically after a few days.)

If you have to transfer email accounts along with the website, the easiest way to do this is to set up the email addresses on the new mail server (i.e. the server that stores the emails, which is usually the same as the Web server), and then change the DNS MX record (which specifies which server handles the email for the domain) on a Friday afternoon. By Monday morning, everyone will know about the change, and you can download all of your email one last time from the old mail server, change your email preferences to reflect the new mail server (and your passwords, if they have changed), and then start checking your email on the new server.

This only applies to POP accounts on which no mail is left on the server. IMAP accounts are more difficult; you’ll have to copy all of your emails off the old server first, and then reupload them to the new server. There are other more immediate methods as well, such as changing the TTL or specifying MX records for both the old and new mail servers at the same time.

Conclusion

The 24 to 48-hour DNS delay is caused by two main factors:

- The time it takes your registrar or host (or other company) to process your DNS request, which could be anywhere from a few minutes to 24 hours. Before this happens, nobody anywhere has any chance whatsoever of knowing about the change.

- The time it takes for your personal name server to learn about the change, which can vary from instantly to the time to live (usually 24 hours). The delay from this will be different for everyone.

Hopefully this article has given you a solid understanding of the basics. Please feel free to comment if you have anything to add or suggest.

Further Reading

- The Effective Strategy For Choosing Right Domain Names

- 10 Tools For Finding, Registering And Managing Domain Names

- Get Creative With Your Domain Name

- Introduction to DNS: Explaining The Dreaded DNS Delay

Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers Register Free Now

Register Free Now Register for free to attend Axe-con

Register for free to attend Axe-con