Design Legacy: A Social History Of Jamaican Album Covers

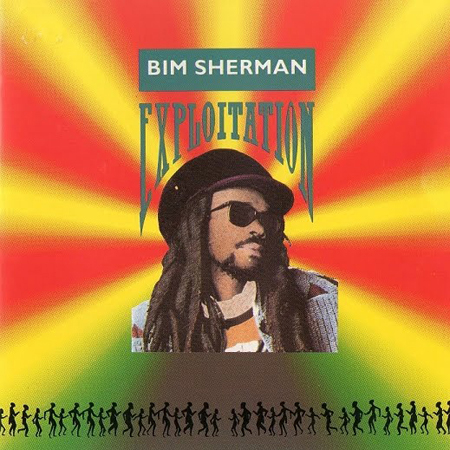

Mention Jamaican music to someone who isn’t a fan and you can bet that a fairly predictable image pops into the head of your listener. Chances are this image looks something like the cover of Bim Sherman’s Exploitation:

For many people, this vision — of roots reggae and its deified lead singer — is the only face that Jamaican music has to offer. (To be honest, the Jamaican music industry, in its eagerness to capitalize on the popularity of this face, hasn’t done much to contradict it.)

Dig a little deeper, however, and you’ll find a dozen genres lurking beneath the tie-died surface of roots reggae. On the album covers belonging to these genres, moreover, you’ll find a dozen different — and sometimes contradictory — visual images of what it has meant to be Jamaican, besides the template of the righteous Rastafarian popularized by Bob Marley. Although the reggae of the 1970s popularized a message of political rebellion, you only have to go back a few years earlier to find album covers that unconsciously reflect the values of neocolonialism — Jamaica as cultural treasure chest waiting to be looted by foreign interests.

Equally complex is the relationship to pop culture: while many covers evidence a conscious Afro-centric opposition to Western society, many others adopt, mimic or are swallowed up by the conventions of American music and movies. You can see every chapter of Jamaica’s modern social history — the burden of colonialism, the optimism surrounding political independence, the social and economic problems that greeted self-rule — reflected in the typographic, illustrative and photographic choices made by its album cover artists over the last fifty years.

In The Beginning

For a country its size, Jamaica has a uniquely prolific music business. In 2000, the industry was estimated to account for 10% of the nation’s GDP (PDF). The footprints of this legacy go as far back as the 1940s, when radios and record players were used to blast American R&B out of storefronts as a means of attracting business. By the 1950s, the phenomenon of the sound system emerged: massive mobile speaker set-ups — run by flamboyant characters with names such as Tom the Great Sebastian — that channeled the music for huge outdoor dances that, in retrospect, look like the distant antecedents of rave culture. With such a uniquely mobilized musical audience in place, it was only a matter of time before the island began to produce its own genres of popular music.

Cultural Plunder In The Ska And Rocksteady Years

Ska “The first indigenous Jamaican pop music was ska, a fusion of American R&B, mento (a local genre of folk music resembling calypso) and other influences. In the late 1950s, local musicians and producers such as Coxsone Dodd, Prince Buster and Duke Reid began experimenting with inverting the typical R&B shuffle beat to move the stress to the after-beat. The result was a new concoction that early listeners sometimes referred to as ‘upside-down R&B.’ In the words of session musician Ernie Ranglin: “Instead of the Chinnk-ka… Chinnk-ka… Chinnk-ka style, we ended up with Ka-chinnk… Ka-chinnk… Ka-chinnk.” Often played by large ensembles with full horn arrangements to stress the after-beat, ska music has an infectious upbeat energy that mirrored Jamaicans’ anticipation of political independence from Great Britain, which would officially arrive in 1962.”

Listen: Girl, Why Don’t You Answer Your Name, Prince Buster

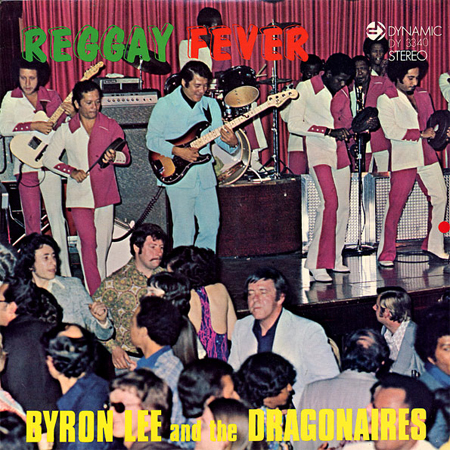

Who was the first international face of Jamaican music? Before Bob Marley, Jimmy Cliff or Desmond Dekker, there was Byron Lee, the country’s original musical export:

This cover actually dates from 1973, but it typifies one way in which Jamaican music had tried to package itself since the beginning of the ska period: music with a light-skinned face (Lee was Chinese-Jamaican), playing for a light-skinned audience. Bright childlike lettering with no sharp edges. A cultural souvenir: exotic dance music with no complicating social narrative.

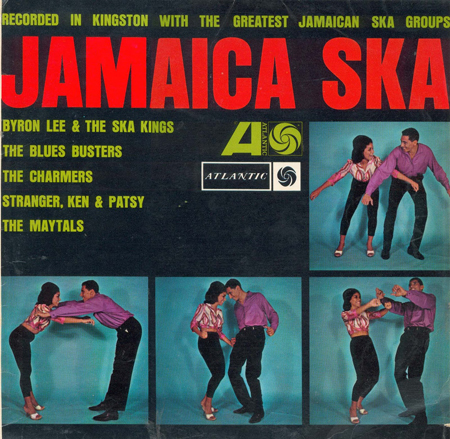

The attempt to market Jamaican music this way emerged at the beginning of the ska period in the 1950s to meet the surging upmarket tourist industry and the interest among American record labels in tapping the island’s music. It peaked at the New York World’s Fair in 1964, with a contrived and unsuccessful effort by the government to plant ska on the world stage and garner attention for the island as a tourist destination. To the great resentment of the musicians involved, the government selected Byron Lee’s Dragonaires as the backing band for this extravaganza — a decision presumably based on the band’s clean-cut presentation and on Lee’s political connections to future Prime Minister Edward Seaga. The affair failed to incite international interest in ska, and the only relic from the experiment is a forgettable album entitled Jamaican Ska, released by the US label Atlantic Records and timed to coincide with the ’64 World’s Fair:

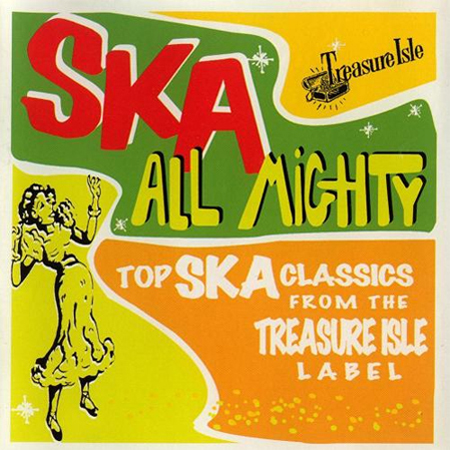

Although the government would never again throw its hat in the ring with the same vigor, the effort to market Jamaican music to an explicitly foreign market would continue for many years to come. Many album covers would include a map of how to get to the island, instructions on how to dance once you get there, and plenty of goofball novelty typography in between.

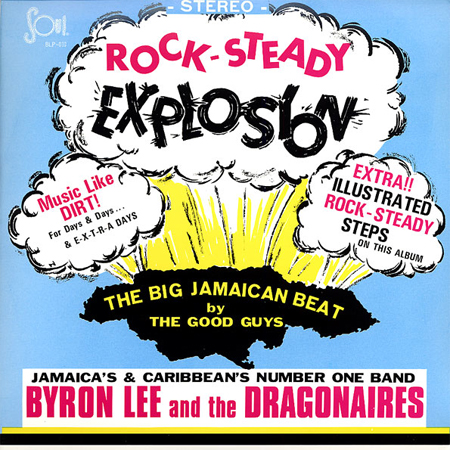

Here’s Byron Lee and his Dragonaires again, “The Good Guys” amidst a dark island:

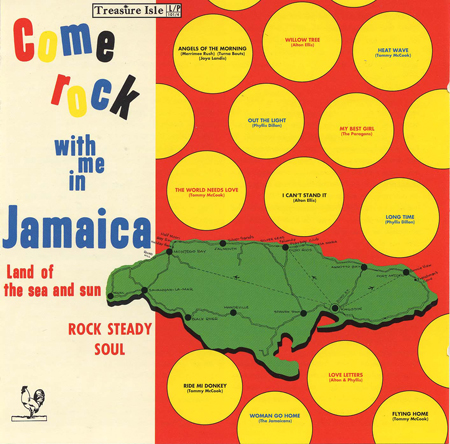

And here’s a rocksteady compilation from the Treasure Island label, complete with copy that seems to have been written by the Jamaica Tourist Board:

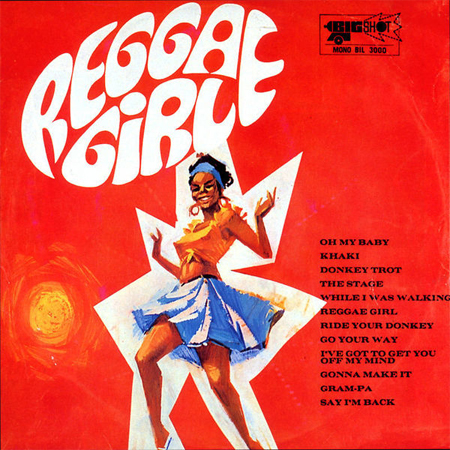

The situation becomes even more dubious when a girl is thrown into the bargain, as offered by several albums from the 1960s:

Not that there’s anything unusual about putting a woman on an album cover — just about every genre in existence has tried it at some point. But it’s the racial tightrope that these covers walk — airbrushing their models to conform to Anglo-American standards of prettiness — and the associations made with pirate loot that make for a slightly queasy viewing experience today.

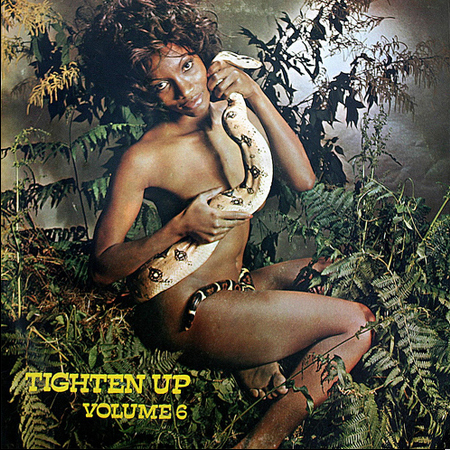

In later years, the most absurd culprit in this category was Trojan’s Tighten Up series, a set of compilations aimed at a white British audience, whose covers often evidenced all the subtlety and cultural sensitivity of early James Bond movies:

None of this commentary is meant to reflect negatively on the music within. Regardless of the cover art, the songs of the ska and rocksteady eras burst with self-assurance and innovation. The point is that these genres reflect an industry that had forged its own musical consciousness but whose marketing and visual identities lagged behind. Even the majority of albums from this period that did not parrot colonial values still took their lead from American R&B covers. (See Chris Morrow’s Stir It Up: Reggae Album Cover Art, pages 17 to 19, for more rocksteady cover art drawn overtly from American R&B and soul albums.)

Egalitarianism In The Rocksteady Years

Rocksteady “In the summer of 1966, the tempo of the music being produced in Kingston suddenly slowed, and music historians have been debating the causes ever since. One explanation is a heat wave that left audiences dying for a mellower beat to sway to. Another is a rising tide of violence at dances: suddenly, you didn’t want to be stepping on the toe of the person behind you. The most compelling explanation is the appearance of the first electric bass on the island — imported, in the irony of ironies, by none other than Byron Lee. While Lee’s interest in the instrument was purely practical — an electric bass was easier to tote around than an upright — the dynamics of the instrument helped shift Jamaican music towards a slower, heavier groove, featuring a smaller cast of musicians and more closely resembling the instrumentation of American soul music coming out of Stax and Motown.”

Listen: Ba Ba Boom, The Jamaicans

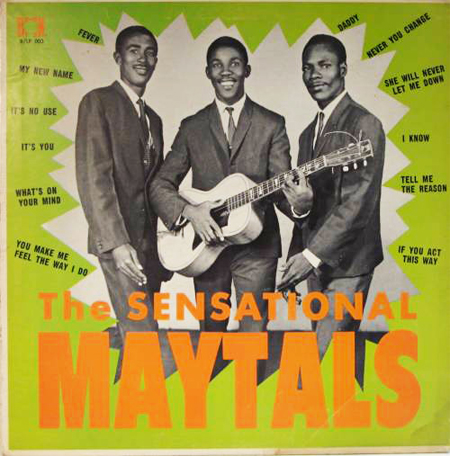

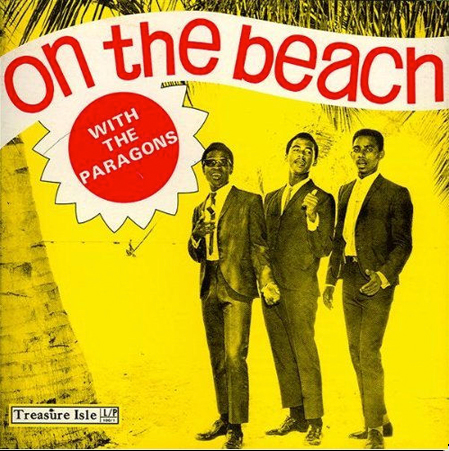

Rocksteady is the genre that took its cue most explicitly from the US soul music of Stax and Motown, and the resemblance led to some distinction in the cover art. Instead of the larger ensembles that played ska music, rocksteady tended to involve a smaller number of musicians, which allowed more room for vocal harmonizing. This in turn created an interesting democratization of the band dynamic: rather than a clearly-defined lead singer with subordinates handling backup, the rocksteady structure often featured a trio on equal footing, each sharing lead duties — and consequently, all enjoying an equal chance at stardom. Covers from this period frequently show three vocalists standing shoulder to shoulder, with no apparent hierarchy:

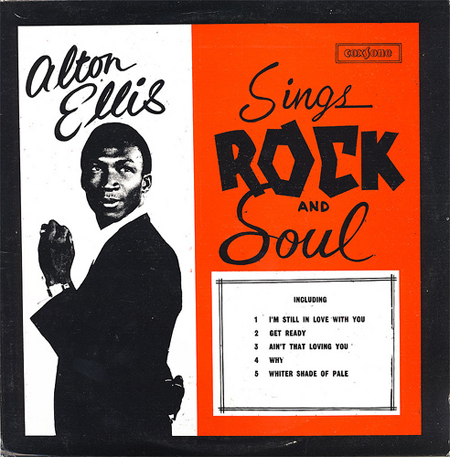

The rocksteady years, while producing some sublime original music, also yielded innumerable remakes of American songs, and many of the covers of the time show expressive ways of communicating this:

The heavy-handed “ROCK” lettering here serves as kind of “buyer beware” label to a Jamaican audience more partial to smooth soul sounds (represented here in script).

Social Consciousness And Self-Indulgence In The Reggae Era

Reggae and Rastafari “In 1968, the first reggae rhythms began to appear as musicians sped the tempo back up again, and increasingly sophisticated organ parts created more room for rhythmic syncopation from the bass and guitars. But the reggae era diverged sharply from rocksteady not just in music but by ushering a new era of political consciousness into Jamaican music. Whereas ska and rocksteady were essentially dance genres created in Kingston, reggae signaled a shift to a rural consciousness, which had always been the stronghold of political dissent in Jamaica and within the Rastafari movement in particular. The term ‘Rastafari’ signals a belief in the messianic status of Haile Selassie (born Ras Tafari), the Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. Shut out of mainstream Jamaican middle-class society until the 1970s — and thus shut out of ska and rocksteady — Rastafari finally bubbled up into the mainstream musical and social consciousness when the political and economic woes of Jamaica grew too great to ignore. Frequently derided as a kind of screwball mysticism, Rastafari is best understood as Jamaica’s native vehicle for black social consciousness, a political movement every bit as much as a religious one.”

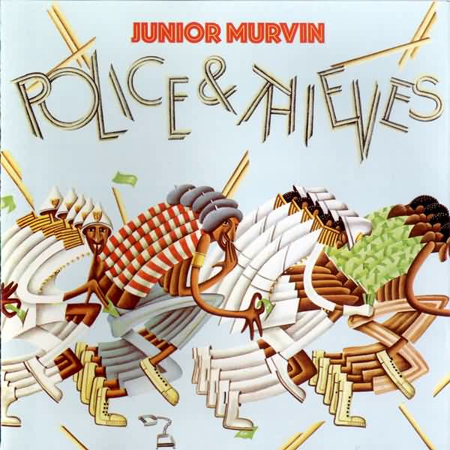

Listen: Police and Thieves, Junior Murvin

As reggae was coalescing as a style in Jamaica, Motown artists Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye were locked in a public struggle with label boss Berry Gordy to buck the company’s rigid hit-factory structure and to make records with greater artistic freedom and social commentary. Although there was no such open insurrection in Jamaica, the shift to reggae signalled an analogous move towards an industry dominated by artists rather than producers. The results mirrored those up in Motown: the songs became longer, the structures more experimental, the lyrics heavier in theme. At its best, reggae was a radicalized version of pop music, with a heavy-hitting political and social relevance unlike anything seen before. At its worst, it showed bouts of self-indulgence that make you yearn for the disciplining hand of the ousted producers who ran the show during the rocksteady years.

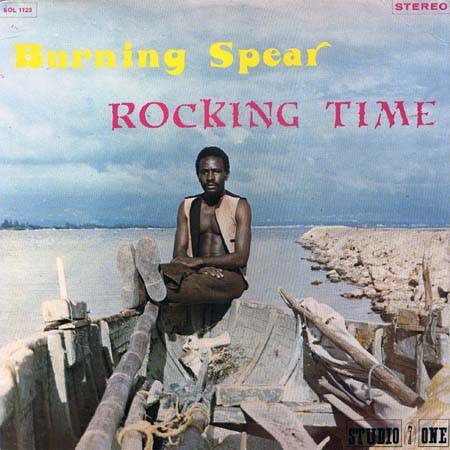

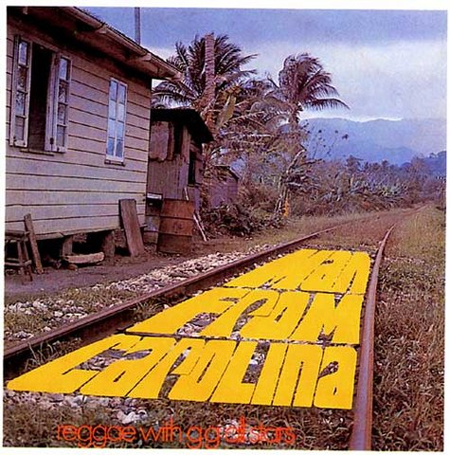

The best photographic covers from this period serve as photo-journalism, taking you right into the rural realities of the third world:

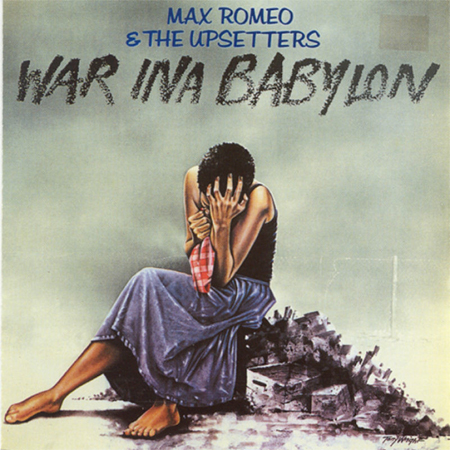

Meanwhile, the best illustrated covers from this period — especially those associated with Lee Perry’s seminal Black Ark studio — take on themes of suffering and political oppression in a style as creative and incisive as the music itself:

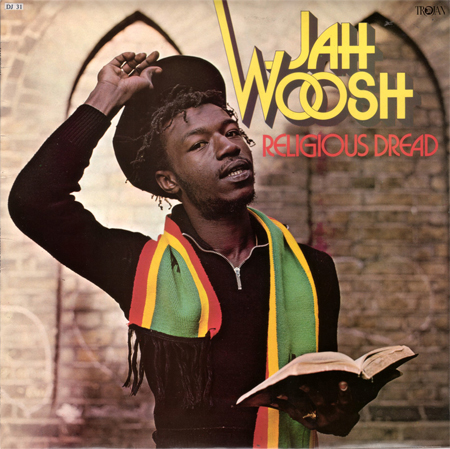

The status of reggae singer as righteous judge passing verdict on society’s injustices inevitably led to a drift to self-indulgence, as well as a monotonous and humorless repetition of certain themes:

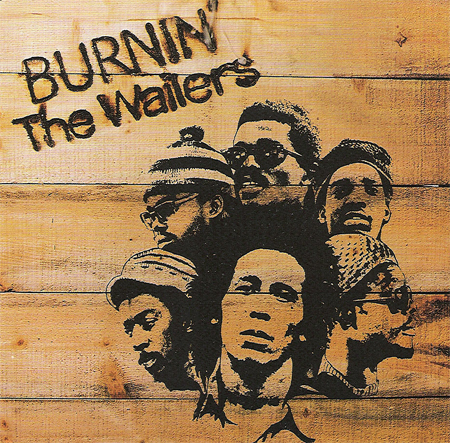

Reggae’s drift from relevance to self-indulgence is especially evident in the album covers of its greatest star, Bob Marley. First, consider Burnin’ (1973), Marley’s last album with the Wailers.

The band is still an ensemble here, with Marley surrounded by his bandmates. While your reaction to this cover might depend on how you feel about wood grain, there’s no denying its immediacy. This feels not like a band of self-satisfied superstars, but rather like a band hungry for insurrection.

Marley’s next album, Catch A Fire, was picked up by Island Records, which made a conscious attempt to promote the artist as a rock star might be promoted, right down to the ostentatious album cover that would have been at home in a gatefold double album by Emerson, Lake & Palmer. The first 2,000 copies of Catch A Fire had a design featuring a giant zippo lighter that is flipped open to reveal the record inside:

In This Is Reggae Music (page 413), Lloyd Bradley writes approvingly of this development: “Up until Catch A Fire, if reggae album artwork didn’t look like publicity material put out by the Jamaican Tourist Board, then it featured somebody’s girlfriend looking nervous, near naked and not very sexy at all.” In retrospect, though, the conscious bloat of Catch A Fire seems more a part of the problem than the solution.

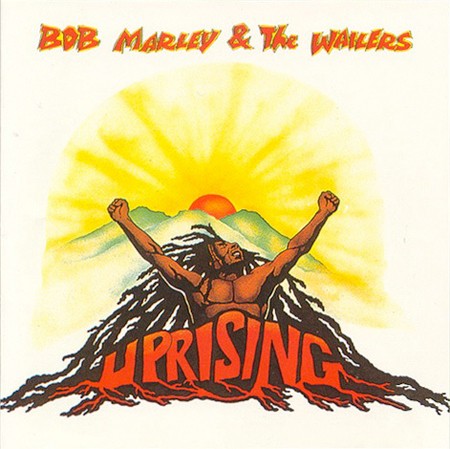

When biographers discuss how Marley was able to achieve superstardom where his peers failed, they often credit the ease with which he learned to play the part of rock god. By the time of Uprising — the last album released in his lifetime — the transformation was complete. The cover helped to cement his messianic status and set the template for the Bim Shermans of the world:

Dub And The Super Ape

Dub “In an industry where sales were built around promoting a hit song on a 7-inch single, producers grappled for decades with the question of what to do with the leftover b-side. In Jamaica, where every penny counted, producers would sometimes save money by creating an instrumental version of the a-side. In the late ’60s and early ’70s, a sound engineer and former radio repairman named Osbourne Ruddock began to experiment with deconstructing and rebuilding these instrumental tracks. Dropping certain elements in and out of the mix, bringing a snatch of vocal track back for ghostly effect, applying echo and reverb from effects boxes of his own devising — anything was fair game. A bystander describes the crowd’s reaction when Osbourne — better known as King Tubby — played his concoction at a dance one of the first times: ‘The crowd did a quick double take and then went wild, pushing down the fence until it was flattened, and then rushed in, knocking the speaker boxes flying’” (from Reggae: The Rough Guide, page 197).

King Tubby and fellow innovators — most notably, Lee “Scratch” Perry — continued pushing the envelope during the decade, creating their own musical idiom in the process and pioneering the role of producer-as-artist that would later find expression in disco, house and other forms of remix-oriented music.

Listen: Roots of Dub, King Tubby

Dub is consciously spooky music, full of cavernous spaces, unexpected collisions and ghostly half-suggested vocal lines. Lloyd Bradley (in This Is Reggae, pages 309–310) describes the “disconcerting” listening experience as “a reach back to Africa”: “The crushing bass ’n’ drum remixes keep us on our toes with such seemingly arbitrary SFX as explosions, crashes, windows breaking and big dogs barking, while through the judiciously employed echo some frighteningly large spaces open up quite suddenly. Such offerings, vividly evoking the smokey intensity of Rasta drumming, were almost allegoric, designed to inspire a notion of simmering, meditative righteousness and to strike dread, both literally and figuratively, into the heart of Babylon. Just as obeah used to scare the crap out of white folks down on the plantation…”

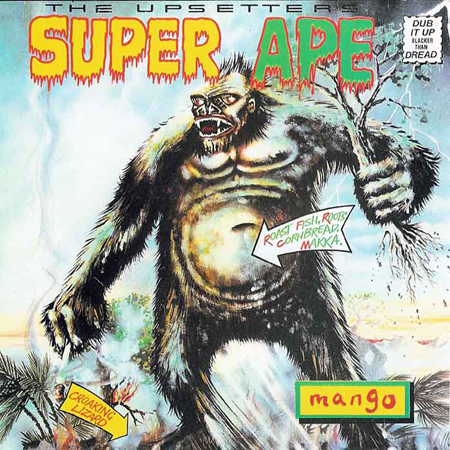

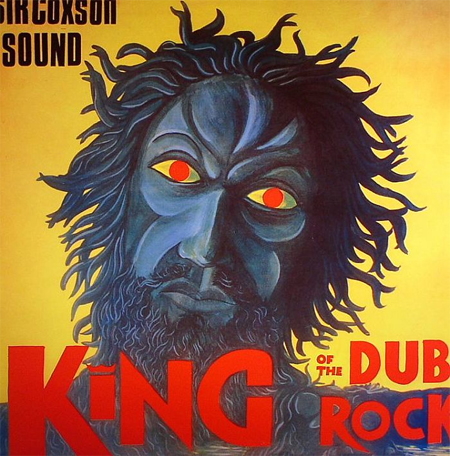

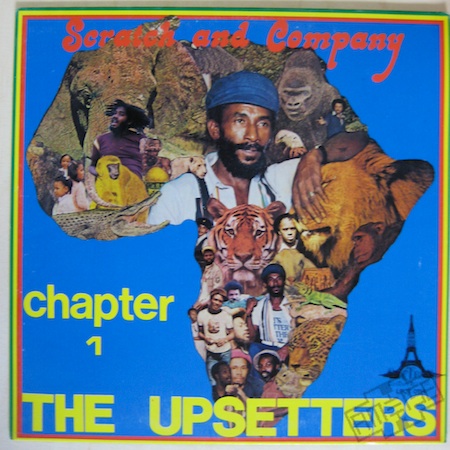

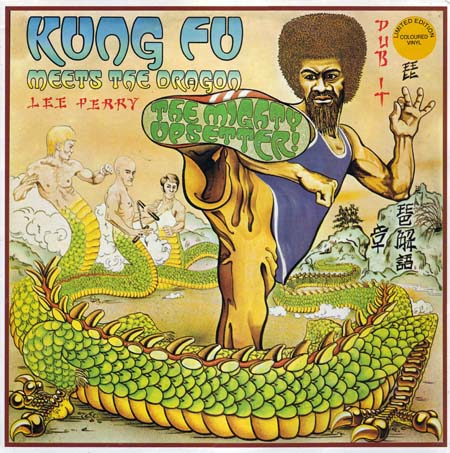

For all its technological forwardness, there is a deliberate African primitivism to dub, a talismanic spookiness. And yet this primitivism is also a bit of a put-on, like a Halloween costume or a fish that blows out its cheeks to appear more gruesome. Many dub album covers from the mid-’70s — especially those belonging to Lee “Scratch” Perry — capture this quality perfectly with their aesthetic of tongue-in-cheek savagery:

Distended Marvel Comics-style lettering… A savage ape, emblematic of Africa… And yet the arrows and diagrammatic comic-book text tell us there’s an ironic self-awareness behind the whole thing.

Here, Coxsone Dodd — who had already been on the scene for about 20 years as a respected producer — wants you to believe that he was recently transformed into a woodcut monster.

The interest in Africa is also made plain on many Black Ark covers from this period, such as Lee Perry’s Chapter 1:

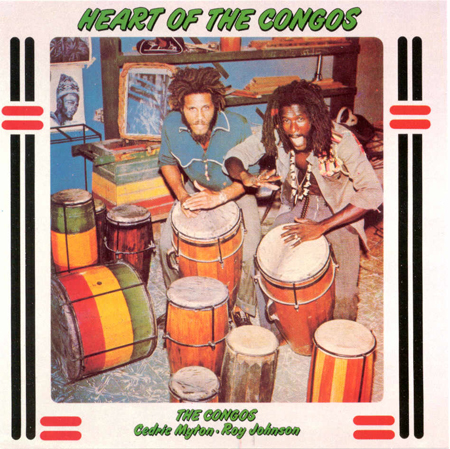

See also the exquisite Heart of the Congos (not a dub album, but a classic Perry production from the mid-’70s nevertheless):

Pop Culture, Movies And Dancehall

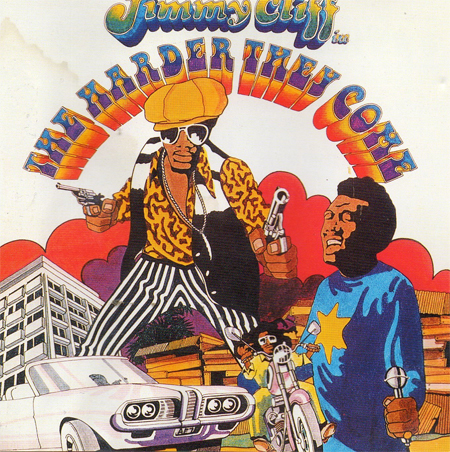

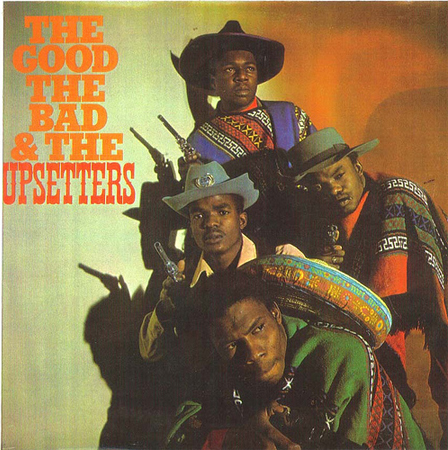

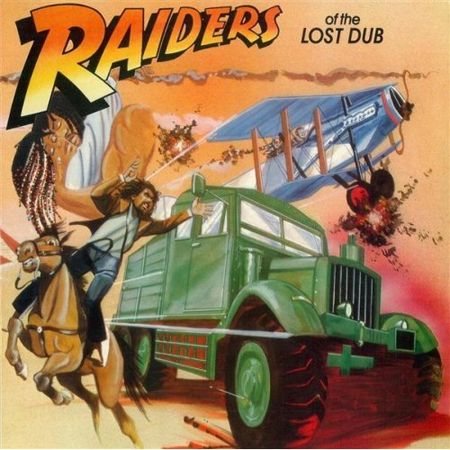

For all of the cultural defiance in some of the reggae album covers of the 1970s, Jamaican music has always been clearly influenced by American popular culture. Part of this stems from the Jamaicans’ love of a good joke, a willingness to subvert almost anything to playful effect. Secondly, Jamaicans love their movies. Thirdly, on an island where so many records are made, parody is in constant supply:

*The Harder They Come* caused a sensation when the major motion picture opened in Kingston. Thousands of people without tickets tried to storm the gates of the cinema. The exquisite illustration and typography owe a debt to both Hollywood Westerns and blaxploitation.

Other times, Jamaicans’ obsession with movies comes across in ways that are overtly silly and farcical:

*The Harder They Come* caused a sensation when the major motion picture opened in Kingston. Thousands of people without tickets tried to storm the gates of the cinema. The exquisite illustration and typography owe a debt to both Hollywood Westerns and blaxploitation.

Other times, Jamaicans’ obsession with movies comes across in ways that are overtly silly and farcical:

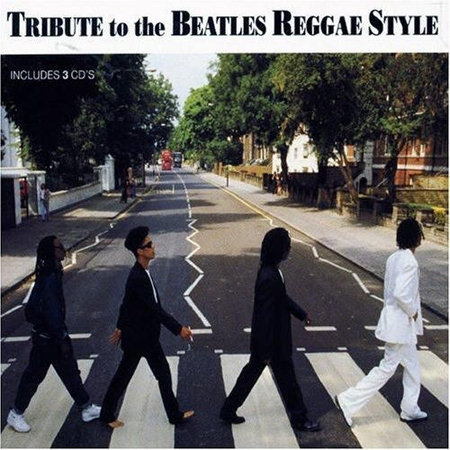

The island’s musicians have shown a willingness to cover just about anything (including Christmas), a tendency that is often perceived as showing a lack of integrity. It would be more apt to view it as part of the famed Jamaican resourcefulness, the habit of mining every last bit of available source material:

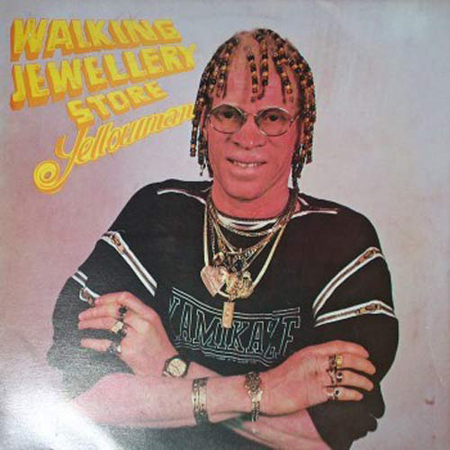

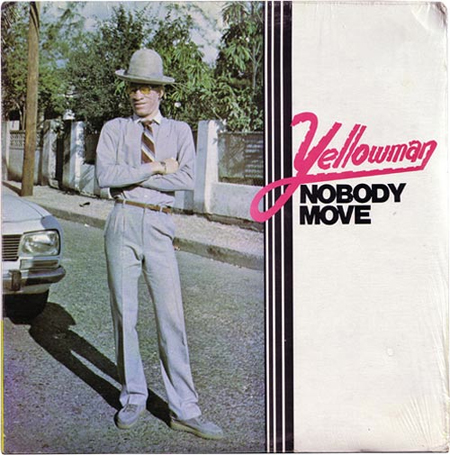

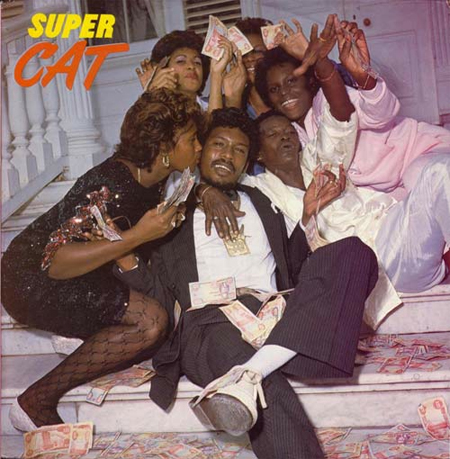

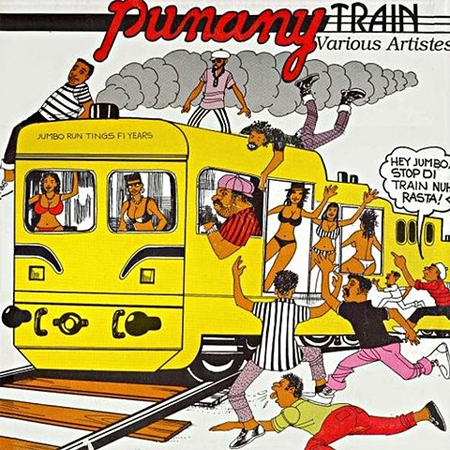

These covers keep a safe satirical distance from the 500-pound gorilla that is US and UK pop culture. But during the dancehall phase of the 1980s, Jamaican sensibilities seem to get swallowed up by the aesthetic of materialism and arrogance in US hip-hop culture:

Credit Yellowman for at least maintaining a grotesque sense of humor in his postures (and, in some cases, a weirdly meticulous sense of photographic composition: check out how his belt aligns perfectly with the receding edge of the sidewalk in the cover above). As the ’70s rolled along, the appropriation of rap culture became depressingly void of self-awareness:

The ’80s: Things Unravel

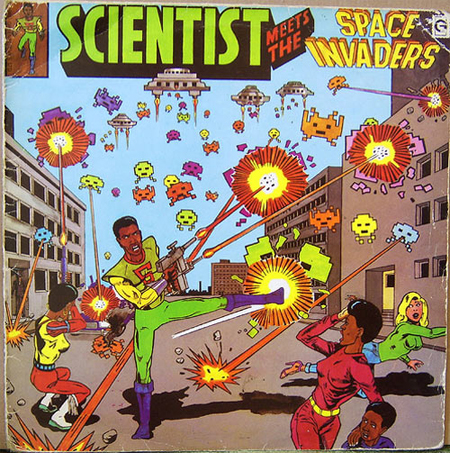

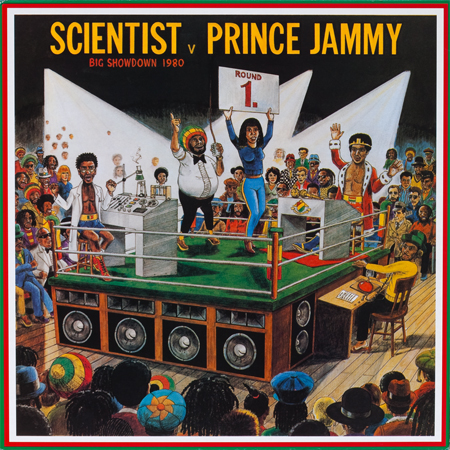

With its lack of lyrical themes, dub music freed up cover artists to illustrate topical subjects and get the albums out onto the street in two to three weeks. London-based designer Tony McDermott, in particular, popularized a fun, irreverent approach to dub cover art in his work for musicians such as Scientist and Mad Professor:

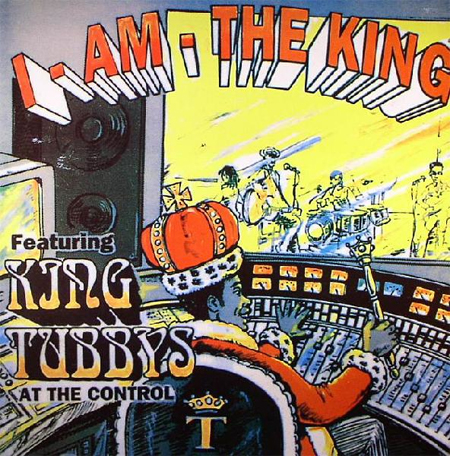

By the mid-’80s, however, the comic-book style degenerated into an excuse to put out bad artwork quickly. These covers often accompanied albums that were themselves hastily assembled or poorly mastered reissue material. After King Tubby was mysteriously murdered outside his recording studio in 1989, for example, his backlog was looted and rushed out the door. This one in particular treats Tubby with all the dignity normally reserved for Burger King’s mascot:

The ’80s in general were a difficult time for the industry. Reeling from the death of Bob Marley and destabilized by the collapse of punk, reggae staggered into the new decade, struggling to find a new identity. The album covers reflect the hard times, as the genre contributed some of the worst covers you’ll ever see from this period. See Crestock’s “42 Reggae Album Cover Designs” for some particularly gruesome examples.

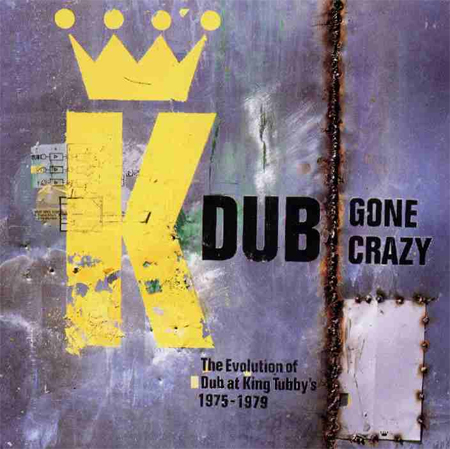

Enter Blood And Fire

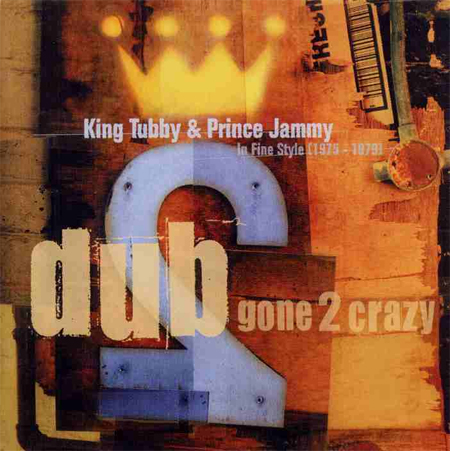

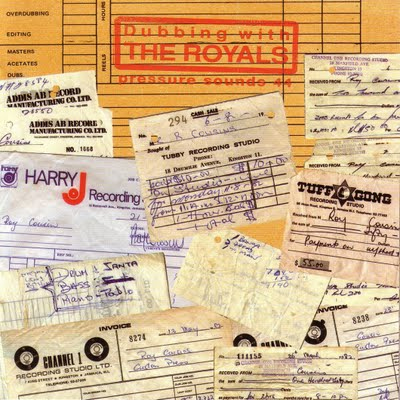

Just when it looked like every idea had been exhausted, every theme mined and every cliche deployed, we’re reminded that the genre can always be visually reinvented with a little fresh thinking. The English label Blood and Fire formed in 1993 with the intention of reissuing Jamaican music to the same standards as jazz and blues, thereby “saving it from the world’s bargain bins and half-price tags,” in the words of founder Steve Barrow. Blood and Fire specializes in dub reissues, and its innovative covers have created a new visual vocabulary for the genre:

Gone are the attempts to personify Tubby as a cartoon character. Also gone, for that matter, are beaches, coconuts, women in bikinis, giant spliffs and every other tired staple of the genre.

In their place are tightly rendered scenes of scrap metal, raw surfaces and found objects: a commentary on the resourcefulness and grit of the producers who made dub music and the interior nocturnal spaces where they worked. Tubby and Lee Perry literally built their own studios, after all, as well as many of the devices and effects boxes therein. One of the great qualities of the Jamaican industry has always been its DIY ethic, which enables the music to stream from its makers to its audience with a minimum of calculation or interference from outside interests. Here is singer Max Romeo talking about the way things were done at Lee Perry’s Black Ark Studio in the 1970s:

“We were just messin’ around with lyrics and the melody. Scratch say: ‘Sounds good.’ He come out and decide to record it right away. It was out on the street in a couple of days. That’s the vibe we had at Black Ark — you didn’t have to say tomorrow or next week. You sound good, you go right now. It was fun days.”– From the liner notes to the Arkology box set (emphasis added).

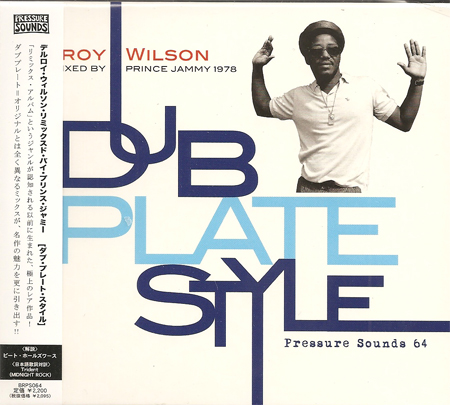

Max Romeo’s memory of a spontaneous musical culture, an environment devoid of record label executives and MTV influence, is what informs Blood and Fire’s album covers. Although Blood and Fire is unfortunately now effectively defunct, the torch has been passed to other labels, such as Pressure Sounds, which has continued to explore ways to creatively package Jamaican reissues:

Conclusion

The modern history of Jamaica is a story that resonates in any number of former European colonies. But of all these countries, Jamaica is the only one whose music industry is so prolific that we can see the whole trajectory written on its album covers. Efforts to keep reggae popular on the world stage have led to a narrow conformist definition of the genre’s visual brand — an ironic fate for a music that is supposed to be about diversity and rebellion. The impressions left behind on Jamaica’s album covers, however, point to a wider and more fragmented social history, one that lacks the conformity of a marketing campaign and that contains the multitude of contradictions in the postcolonial experience.

One For The Road

Quick quiz for design nerds. Why does this posthumous compilation of The Skatalites’ deceased saxophonist include lettering from the Arts and Crafts period?

Answer: Tommy McCook… Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Hey, whatever works.

Other Resources

You may be interested in the following articles and related resources:

- “42 Reggae Album Cover Designs: The Art and Culture of Jamaica,” Crestock If you enjoyed this article, run — don’t walk — to this selection of weird and wonderful album covers, including oddities such as Uglyman’s Ugly Lover.

- This Is Reggae Music, Lloyd Bradley This excellent volume on Jamaican music provides much of the historical context for this article.

- Stir It Up: Reggae Cover Art, Chris Morrow A collection of Jamaican album cover art. Another excellent resource.

- Muzikfan, Alastair Johnston Reviews of Jamaican and world music.

- Reggae: The Rough Guide, Steve Barrow and Peter Dalton

Further Reading

- 35 Beautiful Music Album Covers

- 100 Obscure and Remarkable CD Covers

- Beautiful Covers: An Interview With Chip Kidd

- 29 Cool Music Videos

(al, mrn)

(al, mrn)

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

Register Free Now

Register Free Now Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers