When Typography Speaks Louder Than Words

Clever graphic designers love to use typography to explore the interaction between the look of type and what type actually says. In communicating a message, a balance has to be achieved between the visual and the verbal aspects of a design.

Sometimes, however, designers explore the visual aspect of type to a much greater extent than the verbal. In these cases, the visual language does all the talking. This article explores when the visual elements of typography speak louder than words.

Cal Swan, author of Language and Typography, makes this point well when he says,

“These two distinct areas often come together in practice as there is clearly a very strong relationship between the conception of the words as a message and their transmission in visible form.”

To avoid any misunderstanding, let’s clarify what the terms “visual language” and “verbal language” mean. In professional graphic design, visual language refers to the meanings created by the visual appearance of both text and image. In this article, the term “visual language” refers to the character and significance created by carefully selected typography. Verbal language is the literal meaning of words, phrases and sentences.

In this first of a two-part series, we will look at the powerful effect that typography has in taking control of meaning. We will discuss a range of examples, from verbal language that inspires and shapes visual treatment to visual language that dominates verbal meaning. The implications of typographic choices in meaning and interpretation will also be examined. And we will show how the same message can be presented in a number of ways to convey and encourage a diversity of responses.

We all have different cultural backgrounds and experiences that affect our perception of type one way or another. So, regardless of the designer’s skill and effort, a number of uncontrollable aspects remain, including the viewer’s perception, expectations, knowledge, experiences and preferences. And while accounting for all such unpredictable responses to type is impossible, awareness is critical.

Jump to Part 2: Why Subtle Typographic Choices Make All The Difference

Manipulating Feelings and Reactions

The visual language established when designing with type can bring into play not only emotions, but also physical responses. The following examples are simple illustrations of the varied and emotive effects and highly dominant control that can be achieved by changing the visual language of a message, while still presenting the same verbal language.

This first of a pair of illustrations shows a single large bold word, set in lowercase and closely kerned. The positioning in the frame makes the word dominant and loud, and the message comes across as enthusiastic, friendly and confident. The person speaking is pleased to see you and is coming towards you with a big smile on their face.

The second illustration contrasts dramatically with the first, despite featuring the exact same greeting. The font, case, scale, color and positioning all suggest a considerably more distant and hesitant meeting. In fact, you would be forgiven for thinking that the person speaking here is not at all sure they even want to acknowledge you and would have preferred to ignore you completely.

Reading these examples aloud helps us instantly appreciate the different effects of visual language. If you read the first example out loud, it would be a loud enthusiastic call that exudes genuine delight, friendliness and openness. Reading aloud the second example, the exact same word, it would be delivered in a much quieter tone, an almost hesitant voice, lacking the assurance and delight of the first. There is an infinite range of typographic alternatives that achieve subtle or dramatic changes in volume and tone of voice.

Making The Most Of Visual Language

Verbal language is often used to inspire and shape design and typography in order to get a message across, with the goal being to make the most of the viewer’s reaction. Carefully mixing a design’s implication with literal meaning can lead to a memorable outcome. The following designs are great examples of the effects that can be achieved by employing verbal language that has helped to inspire a visual treatment.

Our first illustration is taken from the work of renowned American graphic designer Herb Lubalin, who was described in a monograph about him by Gertrude Snyder and Alan Peckolick as being “a tenacious typographer, whose graphic concept employed copy, art and typography, and he used available production methods to underline the drama inherent in the message. Idea preceded design.”

Given the subject of this article, this quote is especially fitting. It shows Lubalin as a designer who valued the combined communicative power of language, typography and composition. The book goes on to explain that he used production methods not just for effect but also as a way to emphasize the meaning and message of a project. In Lubalin’s time, these decisions would have entailed manual labor, posing greater limitations than we face today. Finally, this quote confirms that, for Lubalin, concept was of paramount importance and always came before design.

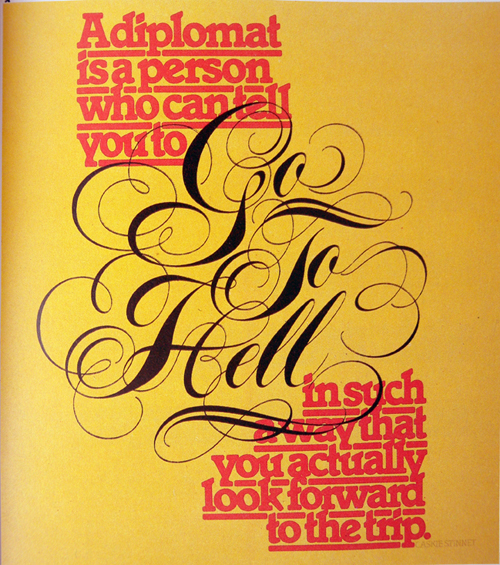

One of his many entries in the Visual Graphics Corporation’s 1964 competition features a carefully selected quote by US editor and writer Caskie Stinnett.

Using delicate and well-considered composition of typographic detailing, Lubalin has succeeded in making an unpleasant message seem attractive and pleasing. The quote states “A diplomat is a person who can tell you to go to hell in such a way that you actually look forward to the trip.” The focal point of this statement, being told to “go to hell,” is shown in an elaborate and elegant calligraphic form, enabling this mildly offensive statement to be mistaken for something that could be looked forward to with great anticipation at first sight.

The work of hand-lettering designer Alison Carmichael provides a range of current examples that beautifully illustrate the powerful effect of typography when it takes control of meaning. One such design is her award-winning self-promotional ad for the Creative Circle. Carmichael’s hand-lettering is engraved and inked in an elaborate style on the lid of an old school desk. At first sight, we seem to be looking at a beautiful, possibly historic, work of gothic lettering; seconds later, reality strikes and the rather unpleasant meaning of the text becomes clear.

Type Tarts is a UK initiative established to raise awareness of the plight of workers trafficked into the sex industry. Contributing designers are asked to send type-oriented “Tart cards” for exhibition. Many London prostitutes advertise their services by displaying promotional cards in phone boxes. Even in the age of the Internet and mobile phones and in the face of police crackdowns, these cards have achieved a cult following, being highly praised and collected as art.

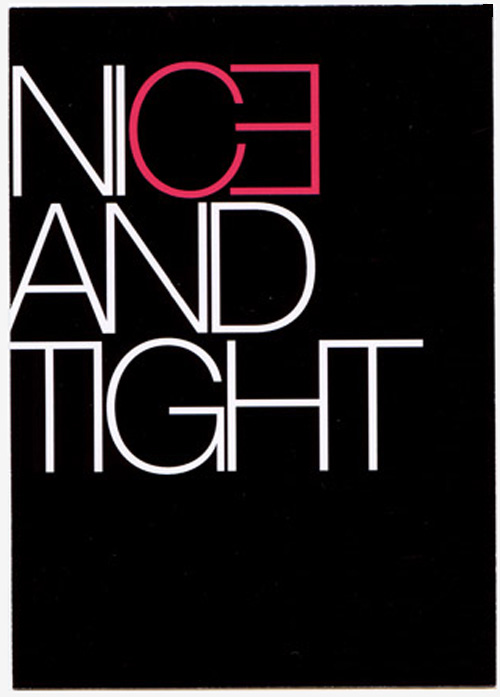

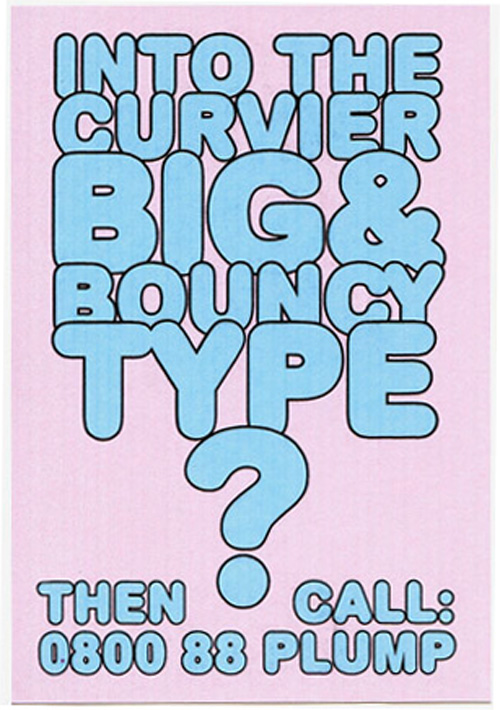

Both examples below use expressive typefaces and type manipulation to visually reinforce the meanings of the provocative text. In the context of the campaign, figuring out the meaning of the cards is easy enough.

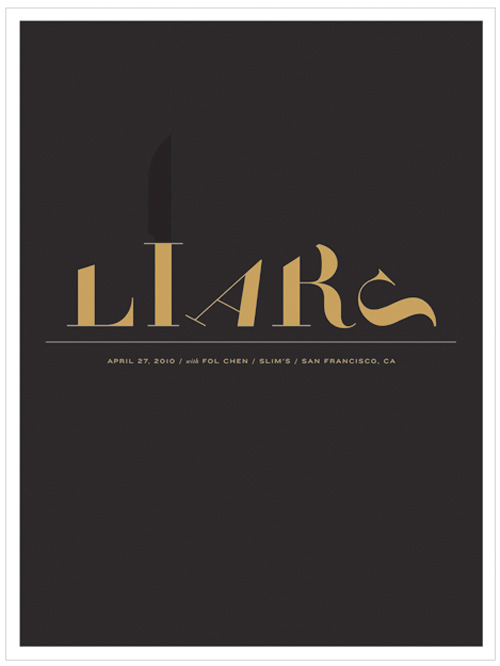

Another stunning example of the visual language of type is by American designer Jason Munn, well known for his highly acclaimed music posters. This example for Liars is mainly typographic, with sections of each letter cleverly removed so that the viewer doesn’t get the full picture. What is the truth? The choice of typeface is also significant; its extreme contrasts of thick and thin strokes point to the contrast between truth and lies.

The designs above use type to reinforce the meaning of their statements. Meanwhile, the British Battleaxe Collection’s visuals for a proposed range of type-based tea towels feature quotes from strong UK female comedy characters. These designs are doing something slightly different; type is used primarily to reinforce the agenda and assertive tone of the speakers.

The example above features a quote from the BBC sitcom Keeping Up Appearances. The words themselves are spoken by the program’s main character — the eccentric, social-climbing and bossy Hyacinth Bucket, a lady in her 60s with grand aspirations. Typographically, the letterforms have been selected and grouped to emphasize the desires of the character. The words “I want” and “my” stand out because of a dramatic change of scale. “Superiors” is emphasized with capital letters, whereas “your” is reduced in size and given lowercase letters, thus downgrading the importance of whom she is talking to, in keeping with the character’s bossy nature and tone of voice when speaking to her milkman.

In this design, the typeface has been dictated by the character’s tone of voice. The serif typeface with its stylish italics and capital letters captures the meaning and cultural context of this statement from a “woman of a certain age.”

Typography is used to communicate tone of voice, personality, age, gender and mood, and it can be easily manipulated. If, instead of this serif font that so successfully represents this woman’s personality, we used a slab serif, suddenly the character changes, as does the emotional impact of the statement. Judging simply by the font, the narrator is no longer definitively female; she is no longer in their mid-60s, and her mood is not merely pompous, but could be described as verging on angry. It’s a great example of how quickly the tone can shift with a simple change of typeface.

The Power Of Typography Cannot Be Underestimated

All the examples discussed in this article demonstrate that typographic treatment works alongside verbal language to create, enhance and alter meaning. While the aesthetic value of design is always important, the significance of type in influencing meaning should not be underestimated.

The role — and, in fact, the obligation — of the designer in establishing a tone that adds meaning to the verbal message is a matter of regular debate. Many graphic designers and academics argue that the designer has a responsibility to add “flavor” to their work, not only helping to convey and enhance meaning, but also making the message enjoyable and encouraging to “read” and also memorable.

In the second part, we’ll continue looking at the relationship between visual and verbal language. We’ll touch briefly on the structure and semiotics of language, as well as showcase some remarkable examples, all helping to explain why subtle typographic changes make all the difference.

Further Resources

- The Herb Lubalin Study Center of Design and Typography

- Herb Lubalin Archive at Cooper Union, Flickr

- Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design, Gunther Kress and Theo van Leeuwen.

Further Reading on SmashingMag

- Massive Collection of Nature Inspired Typography

- Out of This World Typography

- 55 Wonderful Free High-Quality Fonts To Jazz Up Your Designs

- Weird And Wonderful, Yet Still Illegible

Register Free Now

Register Free Now SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers