Design Patterns: When Breaking The Rules Is OK

We’d like to believe that we use established design patterns for common elements on the Web. We know what buttons should look like, how they should behave and how to design the Web forms that rely on those buttons.

And yet, broken forms, buttons that look nothing like buttons, confusing navigation elements and more are rampant on the Web. It’s a boulevard of broken patterns out there.

This got me thinking about the history and purpose of design patterns and when they should and should not be used. Most interestingly, I started wondering when breaking a pattern in favor of something different or better might actually be OK. We all recognize and are quick to call out when patterns are misused. But are there circumstances in which breaking the rules is OK? To answer this question properly, let’s go back to the beginning.

The History Of Design Patterns

In 1977, the architect Christopher Alexander cowrote a book named A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction, introducing the concept of pattern language as “a structured method of describing good design practices within a field of expertise.” The goal of the book was to give ordinary people — not just architects and governments — a blueprint for improving their own towns and communities. In Alexander’s own words:

“At the core… is the idea that people should design for themselves their own houses, streets and communities. This idea… comes simply from the observation that most of the wonderful places of the world were not made by architects but by the people.”

Street cafe in San Diego (Image credit: shanputnam)

A pattern — whether in architecture, Web design or another field — always has two components: first, it describes a common problem; secondly, it offers a standard solution to that problem. For example, pattern 88 in A Pattern Language deals with the problem of identity and how public places can be introduced to encourage mixing in public. One of the proposed solutions is street cafes:

“The street cafe provides a unique setting, special to cities: a place where people can sit lazily, legitimately, be on view, and watch the world go by. Therefore: encourage local cafes to spring up in each neighborhood. Make them intimate places, with several rooms, open to a busy path, where people can sit with coffee or a drink and watch the world go by. Build the front of the cafe so that a set of tables stretch out of the cafe, right into the street. The most humane cities are always full of street cafes.”

For those interested in going further down the pattern 88 rabbit hole, there is even a Flickr group dedicated to examples of this pattern.

The jump from architecture to the Web was quite natural because the situation is similar: we have many common interaction problems that deserve standard solutions. One such example is Yahoo’s “Navigation Tabs” pattern. The problem:

“The user needs to navigate through a site to locate content and features and have clear indication of their current location in the site.”

And the solution:

“Presenting a persistent single-line row of tabs in a horizontal bar below the site branding and header is a way to provide a high level navigation for the website when the number of categories is not likely to change often. The element should span across the entire width of the page using limited as well as short and predictable titles with the current selected tab clearly highlighted to maintain the metaphor of file folders.”

This is all very nice, but we need to dig deeper to understand the benefits of using such a pattern in digital product design.

The Benefits Of Design Patterns

Patterns are particularly useful in design for two main reasons:

- Patterns save time because we don’t have to solve a problem that’s already been solved. If done right, we can apply the principles behind each pattern to solve other common design problems.

- Patterns make the Web easier to use because, as adoption increases among designers, users get used to how things work, which in turn reduces their cognitive load when encountering common design elements. To put it in academic terms, when patterns reach high adoption rates, they become mental models — sets of beliefs in the user’s mind about how a system should work.

Perhaps the strongest case for using existing design patterns instead of making up new ones comes (once again) from architecture. In the article “The Value of Unoriginality,” Dmitri Fadeyev quotes Owen Jones, an architect and influential design theorist of the 19th century, from his book The Grammar of Ornament:

“To attempt to build up theories of art, or to form a style, independently of the past, would be an act of supreme folly. It would be at once to reject the experiences and accumulated knowledge of thousands of years. On the contrary, we should regard as our inheritance all the successful labours of the past, not blindly following them, but employing them simply as guides to find the true path.”

That last sentence is key. Patterns aren’t excuses to blindly copy what others have done, but they do provide blueprints for design that can be extremely useful to designers and users. And so we do need to stand on the shoulders of designers who have come before us — for the good of the Web and users’ sanity. Many have tried to document the most common Web design patterns, with varying levels of success. In addition to the Yahoo Design Pattern Library, there’s Peter Morville’s Design Patterns, Welie.com and, my personal favorite, UI-Patterns.com.

When Patterns Attack

Here’s the “but” to everything we’ve discussed up to now. There is a dark side to patterns that we don’t talk about enough. One doesn’t simply copy a pattern library from a bunch of random places, put it on an internal wiki and then wait for the magic to happen. Integrating and maintaining an internal design pattern library is hard work, and if we don’t take this work seriously, bad things will happen. Stephen Turbek sums up the main issues with pattern libraries in his article “Are Design Patterns an Anti-Pattern?”:

- Design patterns are not effective training tools.

- Design patterns don’t replace UX expertise.

- Completeness and learn-ability are in conflict.

- Design patterns take a lot of investment.

- Design patterns should help non–UX people first.

This article isn’t meant to discuss these issues in detail, so I highly recommend reading Turbek’s post.

For the purpose of this article, let’s assume we’ve done everything right. We have a published and well-known pattern library that enjoys wide adoption within our organization. We treat the libraries as guidelines and blueprints, not laws to be followed without thinking about the problem at hand. The question I’m particularly interested in is, when is it OK to break a widely adopted design pattern and guide users to adopt a new way of solving a problem?

When We Attack Patterns

Despite all of their benefits, most of the Web seems to have little respect for patterns. The most glaring examples of broken design patterns are found in Web forms. Based on years of research, we know how to design usable forms. From Luke Wroblewski’s book Web Form Design to countless articles on things like multiple-column layouts and positioning of labels, we don’t have to guess any more. The patterns are there, and they’re well established. And yet, we see so many barely usable forms online.

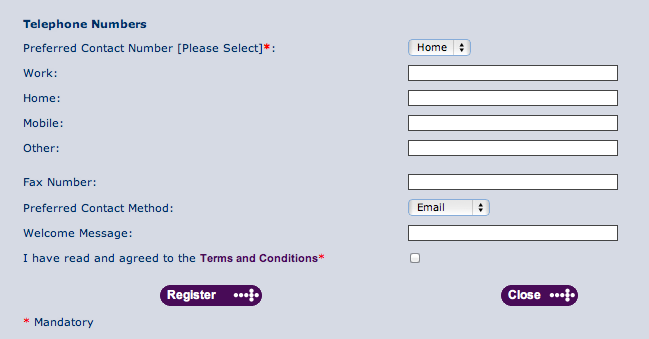

As an example of a broken form pattern, look at the registration form for Expotel below:

Notice the small input fields; the left-aligned labels, with the miles of space between them and the input fields; the placement and design of the “Close” and “Register” buttons, which actually emphasize “Close” more. Oh, and what is a “Welcome Message”? Where will it be used? We can all agree that this is not good form design and is not a good way to break a pattern.

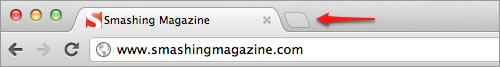

But passing judgment on a broken pattern is not always as easy as it is with the example above. Google’s recent decision to remove the “+” from the button to open a new tab in Chrome came under a bit of fire recently. It breaks a pattern that has been included in most browsers that have tab-based browsing as a feature, and yet Google claims that it did user research before making this change. Was this the right decision?

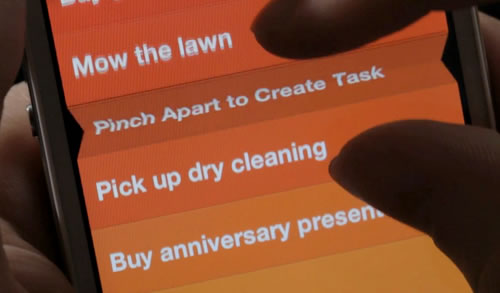

And then there are UIs that we might not know what to make of. iOS apps such as Clear and Path introduce new interactions that we haven’t seen before — to much praise as well as negative feedback. A step forward in design or failed experiments?

As with most design decisions, the answers are rarely clear or black and white. A tension exists between patterns and new solutions that cannot be resolved with a formula. Users are familiar with the established way of doing things, yet a new solution to the problem might be better and even more natural and logical. So, when is changing something familiar to something different OK? There are two scenarios in which we should consider breaking a design pattern.

The New Way Empirically Improves Usability

One of the dangers of iterating on an existing design is what is known as the “local maximum.” As Joshua Porter explains:

“The local maximum is a point at which you’ve hit the limit of the current design… It is as effective as it’s ever going to be in its current incarnation. Even if you make 100 tweaks, you can only get so much improvement; it is as effective as it’s ever going to be on its current structural foundation.”

With patterns, it could happen that we continue to improve an existing solution even while a better one exists. This is one of the pitfalls of A/B testing: it does a great job of finding the local maximum, but not for finding those new and innovative solutions.

We gain much from incremental innovation, but sometimes a pattern is ripe for radical innovation. We need to go into every design problem with our eyes wide open, eager to find new solutions, and ready to test those solutions to make sure that we’re not following bad intuition. As Paul Scrivens points out in “Designing Ideas”:

“You will never be first with a new idea. You will be first with a new way to present the idea or a new way to combine that idea with another. Ideas are nothing more than mashups of the past. Once you can embrace that, your imagination opens up a bit more and you start to look elsewhere for inspiration.”

This is what the Chromium team claims to have done with the “+” button in Chrome. It believes it has found a better solution, and it’s tested it.

The Established Way Becomes Outdated

Think of the icon for the “save” action in most applications. When was the last time you saw a floppy drive? Exactly. Sometimes the world shifts beneath us, and we have to adjust. Failing to do so, we could get stuck in dangerous ruts, as Twyla Tharp attests (quoted by Yesenia Perez-Cruz):

“More often than not, I’ve found a rut is the consequence of sticking to tried and tested methods that don’t take into account how you or the world has changed.”

The publishing industry knows this better than most. Stewart Curry has this to say in “The Trope Must Die”:

“Design patterns can be very useful, but when we’re making a big shift in media, they can sometimes hold progress back. If we look at the evolution of digital publications, it’s been a slow and steady movement from (in the most part) a printed page to reproducing that printed page on a digital device. It’s steady, linear, and not very imaginative, where “it worked in print, so it will work in digital” seems to be the mindset.”

This is where the developers of apps such as Clear and Path are doing the bold, right thing. They realize that we’re at beginning of a period of rapid innovation in gesture-based interfaces, and they want to be at the forefront of that. Some ideas will fail and some will succeed, but it’s important that our design patterns respond to the new touch-based world we’re a part of.

Our design patterns have to adjust not only to a shift in our interaction metaphors, but to a significant shift in technology usage in general. Tammy Erickson did some research on what she calls the “Re-Generation” (i.e. post-Generation Y) and discusses some of her findings in “How Mobile Technologies Are Shaping a New Generation”:

“Connectivity is the basic assumption and natural fabric of everyday life for the Re-Generation. Technology connections are how people meet, express ideas, define identities, and understand each other. Older generations have, for the most part, used technology to improve productivity — to do things we’ve always done, faster, easier, more cheaply. For the Re-Generation, being wired is a way of life.”

Expectations of apps and services change when everything is always on and accessible. We become less tolerant of slow transitions and flows that are perceived to be too complex. We are being forced to rethink sign-up forms and payment flows in an environment where time and attention have become scarcer than ever. We don’t have to reinvent the wheel, but we do need to find better ways to keep it rolling.

The Informed Decision Is The Right Decision

Design patterns bring many benefits, as well as some drawbacks to watch out for. But we’d be foolish to ignore these helpful guidelines. There is no formula for what we need to do; rather, we need to operate within certain boundaries to ensure we’re creating great design solutions without alienating users. Here is what we need to do:

- Study design patterns that are relevant to the applications we are working on. We need to know them by heart — and know why they exist — so that we can use them as loose blueprints for our own work.

- Approach each new project with a mind open enough to discover better ways to solve recurring problems.

- Stay up to date on our industry (as well as adjacent ones) so that we recognize external changes that require us to rethink solutions that currently work quite well but might be outdated soon.

In short, we can neither follow nor ignore design patterns completely. Instead, we need a deep understanding of the rules of human-computer interaction, so that we know when breaking them is OK.

Further Reading on SmashingMag:

- Taking Pattern Libraries To The Next Level

- An Exploration Of Carousel Usage On Mobile E-Commerce Websites

- An In-Depth Overview Of Living Style Guide Tools

- Boost Your Mobile E-Commerce Sales With Mobile Design Patterns

Register for free to attend Axe-con

Register for free to attend Axe-con

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App Register now for WAS 2026

Register now for WAS 2026 Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers