Making A Better Internet

My relationship with the Internet oscillates between waves of euphoria and waves of angst. Some things make me extraordinarily happy: like a client who loves usability testing so much when they first experience it that they can’t sleep for days; or connecting with someone whose writing I’ve admired for many years.

But other things make me want to close my computer forever and go live on a farm somewhere: like people who take entire articles and present them as their own work, with tiny source links at the bottom of the page; or endless arguments and name-calling that ignore even the most basic human dignity.

We are capable of such great things, yet we somehow can’t resist the temptation to tear others apart. There is, perhaps, no better depiction of the current state of the Internet than xkcd’s “Duty Calls”:

Duty Calls by Randall Munroe.

In this essay, I’ll weave together a story about the current state of Internet discourse. At the end, I’ll tell you how I think we can make it better. And then, we’ll most likely all go back to what we were doing and forget about it. Despite the probable futility of this exercise, I’ll carry it out anyway, because I love the Web and I really don’t want us to destroy it.

Act 1: The Lap Dancer

Paul Ford’s “The Web Is a Customer Service Medium” is one of the most important essays of our time. Towards the end, he explains how, in April 2010, the Daily Mail “reported” that “computer tycoon Sir Clive Sinclair, 69, has secretly married his lap dancer fiancee Angie Bowness, who is 36 years his junior.” The appropriate response to this type of story is an overwhelming “Who cares?”, but that’s obviously not what happened. A lot of blogs wrote about it, and the comment sections are sights to behold. Below one of the accounts, a commenter posted the following image in response:

It’s at this point that we need to pick up Paul’s essay for his response:

“Consider what that cartoon means in that context: It implies that the commenter feels — with some irony and self-awareness, I’m sure — that his opinion, in some way, is relevant to the question of whether Clive Sinclair should marry a particular woman. This is, for many obvious reasons, completely insane. And yet there was an image already sketched and available to that commenter so that he could express this exact sentiment of choosing not to be outraged at a situation he read about on the Internet.”

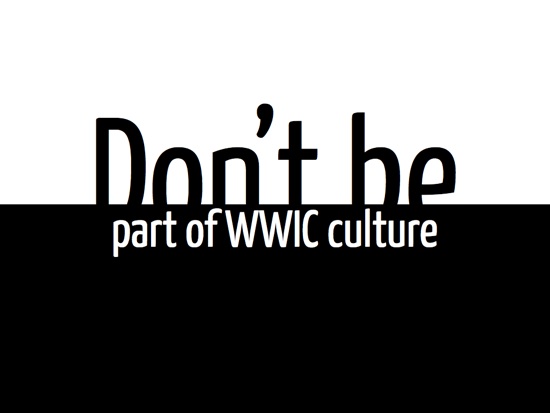

Paul has a phrase for this, a phrase that has shaped my view of the Internet ever since I first read it. He calls this phenomenon “Why Wasn’t I Consulted?” or WWIC. It’s the fuel that powers the Internet — the insatiable desire to be heard, to make your opinion known, to be understood. It’s the new scribbling “[X] was here” on tree trunks. We read, we share, we “curate,” we post pithy statements and ask people to “Like if you agree!!1!” Lest we spend a day not being noticed.

Act 2: The Bottom Half

On 6 August 2012, South African news website IOL posted an article titled “How ANCYL Plans to Shut Down Cape.” Things got a little out of hand, as they usually do on news websites, until the editors deleted all comments and posted the following notice: “IOL has closed comments on this story due to the high volume of racist and/or derogatory comments.” A friend noted that they should probably just hardcode that sentence into the footer.

A search for the origin of the well-known phrase “Never read the bottom half of the Internet” led me to Sophie Heawood, who told me that she first used it in an article for The Independent a couple of years ago. The first online reference we could find is in her article “Save Dappy From the Venom of the Anonymous”:

“What surprises me the most about the bottom half of the internet, that place where all the angry comments go, is that so many of the people writing them turn out not to be rabid murderers but ordinary mild people who casually fire off drive-by verbal shootings in their lunch breaks.”

A friend of Sophie’s and fellow journalist for The Independent, Grace Dent, told me that she often quotes the phrase as follows: “Never read the bottom half of the Internet; it’s where the sediment lies.”

If you’ve spent any time reading comments on YouTube, you’ll most likely agree with this — in theory. Unfortunately, our need to be consulted about everything is a perfect match for our morbid fascination with what others are doing with their need to be consulted. It’s a viscous, self-feeding downward cycle. I often wish that we could adopt this rule from Thomas More’s Utopia:

“There’s a rule in the Council that no resolution can be debated on the day that it’s first proposed. Otherwise someone’s liable to say the first thing that comes into his head, and then start thinking up arguments to justify what he has said, instead of trying to decide what’s best for the community.”

Instead, many of us turn off comments on our own websites instead. It’s not a great solution, but it’s better than losing sleep because of personal attacks and a general sense of meanness towards something you’ve spent a lot of time creating.

Act 3: Turtles, Turtles, Everywhere

“A well-known scientist (some say it was Bertrand Russell) once gave a public lecture on astronomy. He described how the earth orbits around the sun and how the sun, in turn, orbits around the center of a vast collection of stars called our galaxy. At the end of the lecture, a little old lady at the back of the room got up and said: ‘What you have told us is rubbish. The world is really a flat plate supported on the back of a giant tortoise.’ The scientist gave a superior smile before replying, ‘What is the tortoise standing on?’ ‘You’re very clever, young man, very clever,’ said the old lady. ‘But it’s turtles all the way down!’”

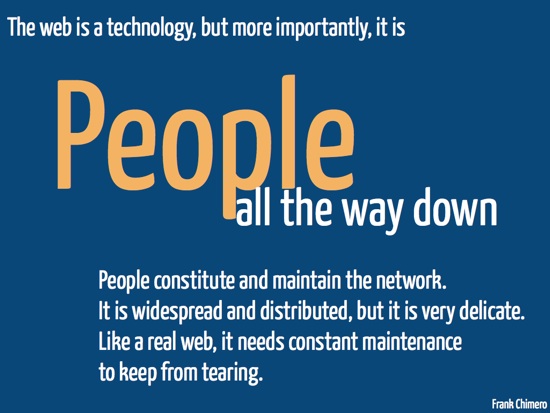

This story, as related by Stephen Hawking in A Brief History of Time, is well known and has entered popular Internet culture in many different ways, from Dr. Seuss, to Stephen King’s Dark Tower, and even as an achievement in World of Warcraft. But it’s Frank Chimero who brought this story to the design world in his essay for The Manual titled “The Space Between You and Me”:

Frank goes on to explain the irony of social media. Social networking websites were created to connect us to each other, and yet they reduce us to a two-dimensional avatar, a short bio and a list of books and movies we like. We’re so quick to throw around the word “empathy” as being essential to the work we do, and yet we know frighteningly little not just about the people who use our products, but even about the people who we think we have close relationships with online.

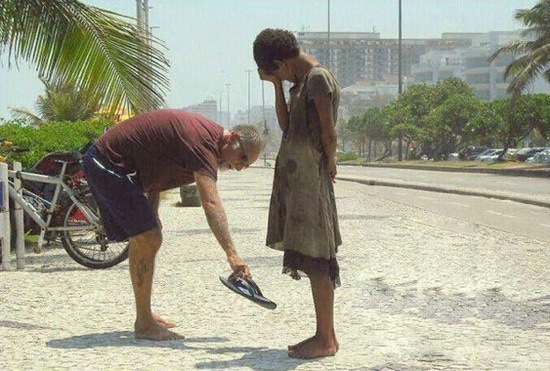

Based on its almost 10 million page views, I’m pretty sure everyone has seen this photograph of a man giving his shoes to a homeless girl in Rio de Janeiro, from BuzzFeed’s “21 Pictures That Will Restore Your Faith in Humanity”:

That’s empathy — a quite literal interpretation of Atticus’s reminder in To Kill a Mockingbird that we need to walk in someone else’s shoes before we judge them. It’s people all the way down, and social media websites are making us forget this by abstracting a person’s “brand” from who they really are.

So, How Do We Make A Better Internet?

In a fit of uncharacteristic optimism, I’d like to propose three ways in which we could make a better Internet. I need to do this before the feeling passes, so let’s get to it.

I know it sounds strange, but not saying something every once in a while is OK. In what some are calling the best social media policy ever written, Benjamin Franklin once said:

“Remember not only to say the right thing in the right place, but far more difficult still, to leave unsaid the wrong thing at the tempting moment.”

It’s tough, but it can be done. The other day, as I stopped at a red traffic light, one of South Africa’s characteristically dangerous taxi drivers came up from behind and swerved around me so that they could run the red light. I was infuriated, but at that point I’d already started thinking about this essay, so I decided not to tweet about it. And then I instantly wanted someone to give me a high five for my remarkable show of restraint. How insane is that? Sometimes, it’s WWIC all the way down as well.

We must resist the temptation to feel entitled to be consulted on everything that happens around us.

A few weeks ago, the Mars Rover made a perfect landing, and at least for a few minutes, the Internet rejoiced with tweets like these:

“‘And Mission, with that, I’d like to break open the peanuts.’ ‘You’re go to break open the peanuts, flight.’I LOVE YOU SPACE NERDS.”— erin kissane (@kissane) August 6, 2012

“That guy with the mohawk and stars cut into his hair is the@curiosityrover engineer in charge of awesomeness.” — Dan Saffer (@odannyboy) August 6, 2012

“An advanced piece of MAN MADE tech is hurtling towards another PLANET to send back new information. And is tweeting. Science f’ing ROCKS.” — Alex Charchar (@retinart) August 6, 2012

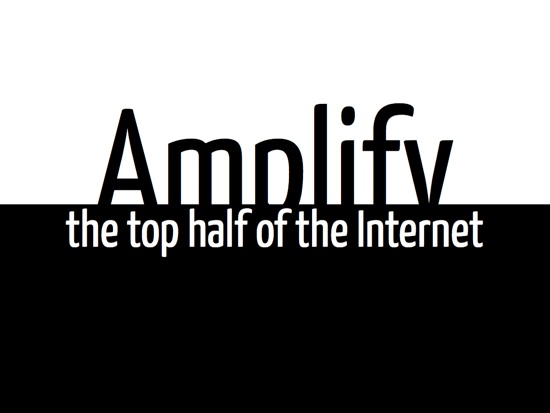

We quickly went back to complaining about other people’s jokes and reactions to the event. But wow! — for a while there, I saw how awesome, encouraging and funny we can be when we pull together to amplify the good things around us.

We don’t have to link to hate speech and angry rants. The best way to stop that behavior is to send traffic elsewhere. We also don’t have to go trolling every time we need a little excitement in our lives. Instead, make and share good things. Be nice. If someone does something good, help them spread the word about it.

I’m pretty sure everyone’s read Jack Cheng’s “The Slow Web” by now, in which he sums up the problem with the environment that we’ve created:

“What is the Fast Web? It’s the out of control web. The oh my god there’s so much stuff and I can’t possibly keep up web. It’s the spend two dozen times a day checking web. The in one end out the other web. The web designed to appeal to the basest of our intellectual palettes, the salt, sugar and fat of online content web. […] The Fast Web is a cruel wonderland of shiny shiny things.”

Contrast that with what Patrick Rhone says in his essay “Twalden”:

“The things I want to know are “happening” — like good news about a friend’s success, or bad news about their relationship, or even just the fact they are eating a sandwich and the conversation around such — I wish to have at length and without distraction. Such conversations remain best when done directly, and there are plenty of existing and better communication methods for that.”

Having conversations “at length and without distraction” — what a novel concept.

But let’s bring this full circle, all the way back to Paul Ford. In the closing keynote at the 2012 MFA Interaction Design Festival, he said the following:

“If we are going to ask people, in the form of our products, in the form of the things we make, to spend their heartbeats on us, on our ideas, how can we be sure, far more sure than we are now, that they spend those heartbeats wisely?”

I’m not saying we should shun the Fast Web and all make Instapaper clones. The Fast Web has its place. I’m also not saying we should quit Twitter. But I do, with all my heart, believe that we — designers and developers — are the ones who are responsible for making a better Internet. And that means we are responsible for how other people spend their time.

We can either take it easy and play to WWIC and bottom-half-of-the-Internet culture, or we can do it the hard way and think carefully about the meaning of the things we make and share. We can choose to ignore our darker tendencies and instead take responsibility for our users and how we ask them to spend their heartbeats. We can shift the flow of traffic away from the bottom half, all the way to the top.

Further Reading

- Guidelines For “Green” Web Design

- 35 Gorgeous PDF Posters: Redesign The Web

- Designing For The Future Web

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

Register Free Now

Register Free Now Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers