Introduction To Polygonal Modeling And Three.js

When the third dimension is introduced into an entertainment medium, it forever changes the way that medium is presented and consumed. The photorealism of the CGI dinosaurs in Jurassic Park opened the doors for film creators to use computers to create visual environments that never would have been possible otherwise. VeggieTales spawned a new type of cartoon, one that uses 3-D objects instead of drawings and which inspired the creation of everything from Pixar and Dreamworks blockbusters to Saturday morning cartoons.

Computer software was greatly affected by this new trend in visual media. 3-D computer games such as Wolfenstein 3D, Quake and Doom reinvented PC gaming, and classic franchises that inspired a generation with their two-dimensional games, such as Super Mario Bros and Zelda, were being updated to 3-D in their subsequent titles.

Until the advent of the official WebGL specification in 2011, this three-dimensional trend had not gotten far in penetrating the Web and the browser. In the last few years, though, we have seen advancements in the use of 3-D models and animations on the Web similar to the trends in television, film and native software.

WebGL demonstrations, like the combined efforts of Epic and Mozilla to create a purely browser-based version of Epic Citadel, point to the massive potential of this new technology. Remembering the trouble of running Unreal Tournament natively on my old ’90s desktop, I find it mind-boggling that this type of presentation can now be used with our Web browsers.

Epic Citadel by Mozilla and Epic. (Larger view)

An important catalyst for the interest in 3-D among Web developers was the creation of the Three.js JavaScript library by Ricardo Cabello (or Mr.doob). The goal of the project is to enable developers with little 3-D and WebGL experience to create incredibly sophisticated scenes using common JavaScript practices. Simply being knowledgable in JavaScript and the basics of modeling is more than enough to get started.

Setting The Scene

While you can hack with Three.js without having worked with 3-D software, to take advantage of the depth of the API, you should grasp the basics of modeling and animation. We’ll look at each of the parts that make up a scene and how they interact with each other. Once we understand these fundamentals, applying them to our Three.js demo will make much more sense.

The Mesh

The skeleton that makes up the shape of the 3-D objects we will be working with is commonly referred to as the mesh, although it is also called a wireframe or model. The mesh type typically used and the one we will use here is the polygonal model.

(Two other types of meshes are used to model 3-D objects. Curve modeling entails setting points in the scene that are connected by curves that shape the model. Digital sculpting involves using software that mimics actual substances. For instance, rather than working with shapes and polygons, it would feel more like sculpting out of clay.)

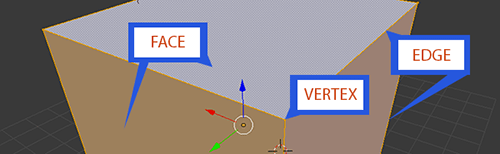

The meshes that make up a polygonal model consist of three parts: faces, edges and vertices. The faces are the individual polygons you see while viewing a mesh and that give the object its shape and structure. Edges run along the outside of the faces and are the connections between vertices. A vertex is the point where any number of these edges intersect. If the mesh is planned out and built correctly, then each vertex will be both at the intersection of edges and at the corners of the adjoining faces.

This allows the faces and edges to be pushed along with the vertices, and it explains why moving vertices in a full model is the most common and effective way to sculpt. Each of these parts is a separate and selectable entity with differing behaviors.

Faces, vertices and edges on a polygonal cube. (Larger view)

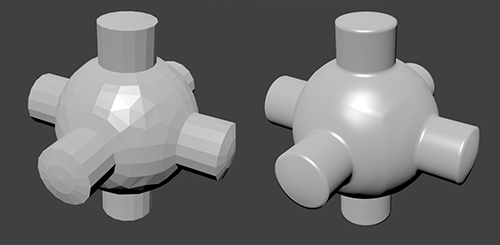

Polygonal modeling makes more sense for use in the browser than other types, not only because it is much more popular, but also because it takes the least amount of time for the computer to render. The downside to this saved speed is that polygons are planar and cannot be curved. This is why a raw 3-D model looks “blocky.”

To combat this issue, programs such as Blender, Maya and 3ds Max have a smoothing utility, used before exporting, that adds many tiny polygons to the model. Adding these polygons along a curve creates many small angles where a previously sharp angle of two large polygons used to meet, giving the illusion of smoothness.

Polygonal shape next to its smoothed counterpart. (Image: Blender| Larger view)

While using meshes, it is possible to use different materials to get different behaviors and interactions. A basic mesh and material will render as flat polygons, showing the model in flat color. Using a lambert material will keep light from reflecting off of the surface and is generally regarded as non-shiny. Many prototypes are created in lambert materials in order to focus on the structure, rather than the aesthetics. Phong materials are the opposite, instead rendering shiny surfaces. These can show some really fantastic effects when combined with the correct use of light.

In addition to these mesh materials, materials for sprites, particles and shaders can all be applied similarly.

(A polygonal model is called “faceted” because it consists of polygonal faces that define the shape of the structure.)

Cameras

In order for these meshes to be rendered, cameras must be placed to tell the renderer how they should be viewed. Three.js has two types of cameras, orthographic and perspective. Orthographic projections eliminate perspective, displaying all objects on the same scale, no matter how far away from the camera they are. This is useful for engineering because differing sizes due to perspective could make it difficult to distinguish the size of the object. You would recognize orthographic projections in any directions for assembling furniture or model cars. The perspective camera includes properties for its location relative to the scene and, as its name implies, can render the size of the model based on the properties’ distance from the camera.

The cameras control the viewing frustum, or viewable area, of the scene. The viewing frustum can be pictured as a box defined by its near and far properties (the plane where the area starts and stops), along with the “aspect ratio” that defines the dimensions of the box. Any object that exists outside of viewing frustum space is not drawn in the scene — but is still rendered.

As expected, such objects can needlessly take up system resources and need to be culled. Culling involves using an algorithm to find the objects that are outside of the planes that make up the frustum and removing them from the scene, as well as using data structures such as an octree (which divides the space into node subdivisions) to increase performance.

Lighting

Now that a camera is capturing the way the object is being rendered, light sources need to be placed so that the object can be seen and the materials behave as expected. Light is used by 3-D artists in a lot of ways, but for the sake of efficiency, we’ll focus on the ones available in Three.js. Luckily for us, this library holds a lot of options for light sources:

- Point. Possibly the most commonly used, the point light works much like a light bulb and affects all objects in the same way as long as they are within its predefined range. These can mimic the light cast by a ceiling light.

- Spot. The spot light is similar to the point light but is focused, illuminating only the objects within its cone of light and its range. Because it doesn’t illuminate everything equally as the point light does, objects will cast a shadow and have a “dark” side.

- Ambient. This adds a light source that affects all objects in the scene equally. Ambient lights, like sunlight, are used as a general light source. This allows objects in shadow to be viewable, because anything hidden from direct rays would otherwise be completely dark. Because of the general nature of ambient light, the source position does not change how the light affects the scene.

- Hemisphere. This light source works much like a pool-table light, in that it is positioned directly above the scene and the light disperses from that point only.

- Directional. The directional light is also fairly similar to the point and spot lights, in that it affects everything within its cone. The big difference is that the directional light does not have a range. It can be placed far away from the objects because the light persists infinitely.

- Area. Emanating directly from an object in the scene with specific properties, area light is extremely useful for mimicking fixtures like overhanging florescent light and LCD backlight. When forming an area light, you must declare its shape (usually rectangular or circular) and dimension in order to determine the area that the light will cover.

To take advantage of area lights in Three.js, you must use the deferred renderer. This renderer allows the scene to render using deferred shading, a technique that renders the scene in two parts instead of one. In the first pass-through, the objects themselves are rendered, including their locations, meshes and materials. The second pass computes the lighting and shading of all of the objects and adds them to the scene.

Because the objects are fully formed in the scene during this computation, they can take into account the entirety of adjacent objects and light sources. This means that these computations need to be done only once, each time the scene renders, rather than once per object rendered.

For example, when rendering five objects and five light sources in the scene with a usual renderer, it will render the first object, then calculate lighting and shading, then render the second object and recalculate the lighting and shading to accomodate both objects. This continues for all five objects and light sources. If the deferred renderer is used, then all five objects will be rendered, and then the light sources and shading will be calculated and added, and that’s it.

As you can see, this can have a tremendous benefit with rendering times when using many light sources and objects. Several disadvantages would keep you from using the deferred renderer unless it’s needed, including issues with using multiple materials, as well as the inability to use anti-aliasing after the lighting is added (when it is really needed).

Adding To The Mesh

Because the mesh is covered by the chosen material and rendered in a view with lighting, aesthetic applications can be done to the top of the mesh. Using textures, you can overlay bitmaps to parts of the object to illustrate it. This is an extremely functional way to bring the models to life, and as long as the structure is created with care, it can look flawless on top of the meshes. Shaders can also be applied using a special type of material that shades the object specifically, regardless of the lighting.

Three.js

Now that we understand the fundamentals of 3-D development using polygonal meshes, we can apply them in the Three.js library. Arguably, the greatest part of the Three.js library is the ability to create fantastic scenes purely from experimentation. In this spirit, we’ll develop a simple demo of a rolling rock to showcase some of the basics we’ve learned and the various implementations we can make, with the expectation that you can take it from there.

Start the Project

First, you’ll want to set up your HTML and canvas, and include the library in your document.

<html>

<head>

<title>My first Three.js app</title>

<style>

canvas { width: 600px; height: 600px; }

</style>

</head>

<body>

<script src="three.min.js"></script>

<!-- <script src="Detector.js"></script> -->

<!-- <script src="stats.min.js"></script> -->

<script>

// Three.js code here

</script>

</body>

</html>

Two other JavaScript libraries that are worth looking into but not required for this demo are commented out in the snippet above.

Detector.js is included in the Three.js examples and detects whether WebGL is supported. It works similar to the Modernizr library in implementation.

Stats.js is a JavaScript performance monitor created by the same Mr.doob who created the Three.js library. It appends a small box that indicates both frames per second and the time needed to render a frame. This can be extremely helpful during development because 3-D animations can be extremely taxing on system resources. Monitoring this box keeps you informed in real time on what models or actions are causing low frame rates in your scene.

As we begin to set up the scene, note how much work the API is doing for us; most of our work at the beginning involves no more than setting up the constructors and properties. We will be using the library to set up the scene in the same way that it would be set up in 3-D software.

- Create the renderer.

- Initiate the scene.

- Create and position the cameras.

- Set up the mesh by combining a new material and new geometry.

- Create and position the light source.

- Write a function that will render the scene in each frame.

Adding Three.js Objects

Before setting up the scene, we need to declare a renderer, set its size, and append it to the window so that we can see what we’re working on.

var renderer = new THREE.WebGLRenderer();

renderer.setSize(600,600);

document.body.appendChild(renderer.domElement);

If you decided to include the Detector.js that was mentioned, you can instead use the following line to check for WebGL support and include a degradation to the canvas renderer if it is not.

var renderer = Detector.webgl? new THREE.WebGLRenderer(): new THREE.CanvasRenderer();

Now that the renderer is included, let’s initiate the scene:

var scene = new THREE.Scene();

Then the camera:

// Syntax

var camera = new THREE.PerspectiveCamera([fov], [aspect ratio], [near], [far]);

// Example

var camera = new THREE.PerspectiveCamera(45, 600/600 , 0.1, 1000);

Note that each camera uses a separate constructor. Because we plan to view the scene in three dimensions, we’re using the perspective camera. The first of the properties is the field of view in degrees; so, our view would be at a 45° angle. The aspect ratio is next and is written as width/height. This could obviously be written as 1 here because our scene is going to fit our 600 × 600-pixel canvas. For a 1200 × 800-pixel scene, it would be written as 1200⁄800 or 12⁄8; and if you want the aspect to constantly fit the window, you could also write window.innerWidth / window.innerHeight. The near and far properties are the third and fourth, giving near and far limits to the area that is rendered.

Placing the camera requires only setting the z-position.

camera.position.z = 400;

We now need to create a mesh to place in the scene. Three.js eliminates the need to create basic meshes yourself, by including the creation of these in its API by way of combining the geometry and material. The only property we must specify is the radius of the geometry.

var geometry = new THREE.SphereGeometry(70);

While it has defaults, specifying the width and height of the segments is also common. Adding segments will increase the smoothness of the mesh but also decrease performance. Because this is only a rock, I’m not too worried about smoothness, so we’ll set a low number of segments. The segment properties are the next two after the radius, so add them the same way.

var geometry = new THREE.SphereGeometry(70,10,10);

To create a mesh out of this new geometry, we still need to add a material to it. Because we want this rock to really show off the light coming from our perspective camera, we’ll add the shiny phong material. Adding this material is as simple as calling it and setting the color property. Notice that the hex color requires the 0x prefix, indicating that it is a hex value.

var material = new THREE.MeshPhongMaterial( { color: 0xe4e4e4 } );

In Three.js, the actual mesh is created by combining the geometry and material. To do this, we just have to call the Mesh constructor and add both the geometry and material variables as arguments.

var sphere = new THREE.Mesh(geometry, material);

Now that the mesh is declared, we can add it to the scene.

scene.add(sphere);

Recalling the introduction, a mesh needs a light source in order to be viewed properly. Let’s create a white light in the same way we initiated the mesh; then we’ll specify exactly where we want the light to be placed and add it to the scene in the same way we added the mesh.

var pointerOne = new THREE.PointLight(0xffffff);

The positions can be written in one of two ways, depending on what you are trying to accomplish.

// Separately:

pointerOne.position.x = -100;

pointerOne.position.y = -90;

pointerOne.position.z = 130;

// Or combined:

pointerOne.position.set(-100,-90,130);

// Add to the scene the same way as before.

scene.add(pointerOne);

Render The Scene

We have everything we need for a basic scene, so all that’s left is to tell the renderer to run by creating a render loop. We’ll use requestAnimationFrame() to inform the browser of the upcoming animation, and then start the renderer with the scene we’ve created. Note that requestAnimationFrame() has limited support, so check out Paul Irish’s shim to make sure all of your users get the same experience.

var render = function () {

requestAnimationFrame(render);

renderer.render(scene, camera);

};

render();

If you open this in your browser, you’ll see the ball in the middle of the canvas with the light reflecting off of it. At this point, play around with the properties to get a better idea of how small changes affect the scene.

Now that the scene is rendered, we can add a simple animation as a starting point. The render loop is already firing every animation frame, so all we have to do is set the speeds, and then we can view the animation right away.

var render = function () {

requestAnimationFrame(render);

sphere.position.x += 1; // Move along x-axis towards the right side of the screen

sphere.position.y -= 1; // Move along y-axis towards the bottom of the screen

sphere.rotation.x += .1; // Spin left to right on the x-axis

sphere.rotation.y -= .1; // Spin top to bottom on the y-axis

renderer.render(scene, camera);

};

render();

Giving Control To The User

If you’re interested in Three.js for game creation, then you’ll want the user to be able to interact with the models on the screen. Map the commands like sphere.position.x +=1 to character-key codes, which will give the user control (in this case, by using the W, A, S and D keys to move). A simple switch statement will assign the key codes to the position changes. Combining position changes with the opposite rotation change will make the ball appear to roll (for example, position.y += 3 with position.x -= 0.2).

window.addEventListener('keydown', function(event) {

var key = event.which ? event.which : event.keyCode;

switch(key)

{

case 87:

sphere.position.y += 3;

sphere.rotation.x -= 0.2;

break;

case 65:

sphere.position.x -= 3;

sphere.rotation.y -= 0.2;

break;

case 83:

sphere.position.y -= 3;

sphere.rotation.x += 0.2;

break;

case 68:

sphere.position.x += 3;

sphere.rotation.y += 0.2;

break;

}

}, false);

If you want to also include the Stats.js library, then add it to your document with the following snippet:

var stats = new Stats();

stats.setMode(1);

stats.domElement.style.position = 'absolute';

stats.domElement.style.left = '0px';

stats.domElement.style.top = '0px';

document.body.appendChild( stats.domElement );

setInterval( function () {

stats.begin();

stats.end();

}, 1000 / 60 );

Going back to the demo, you should have a rock that rolls in the direction of your key press, along with statistics running in the corner if you choose.

Conclusion

This article barely scratches the surface of the Three.js library, as you can see by reading through the documentation. Once you are comfortable with the API, experimenting with particles, mapping and more complicated meshes can yield incredible results.

If you want to better understand how to work in 3-D but don’t have access to Maya or 3ds Max, then Blender is available for free. If you would rather stay in the browser, a few sandbox apps were created in Three.js that will work for you. An editor can be found on the Three.js home page. An alternative is actually a featured project on the home page called ThreeFab and is currently in alpha.

Three.js is a gold mine for creating beautiful and complex Web experiments. Taking the extremely simple demonstration explained here and turning it into a mind-blowing experiment merely takes experimentation and the willingness to try new things. It doesn’t get much better than digging into this library and into WebGL to create something like this.

Further Reading

- Simple Augmented Reality With OpenCV, Three.js And WebSockets

- Building Shaders With Babylon.js

- Why AJAX Isn’t Enough

- A Guide To Audio Visualization With JavaScript And GSAP (Part 1)

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers

Register Free Now

Register Free Now