How To Build And Develop Websites With Gulp

Optimizing your website assets and testing your design across different browsers is certainly not the most fun part of the design process. Luckily, it consists of repetitive tasks that can be automated with the right tools to improve your efficiency.

Gulp is a build system that can improve how you develop websites by automating common tasks, such as compiling preprocessed CSS, minifying JavaScript and reloading the browser.

In this article, we’ll see how you can use Gulp to change your development workflow, making it faster and more efficient.

What Is Gulp?

gulp.js is a build system, meaning that you can use it to automate common tasks in the development of a website. It’s built on Node.js, and both the Gulp source and your Gulp file, where you define tasks, are written in JavaScript (or something like CoffeeScript, if you so choose). This makes it perfect if you’re a front-end developer: You can write tasks to lint your JavaScript and CSS, parse your templates, and compile your LESS when the file has changed (and these are just a few examples), and in a language that you’re probably already familiar with.

The system by itself doesn’t really do much, but a huge number of plugins are available, which you can see on the plugins page or by searching gulpplugin on npm. For example, there are plugins to run JSHint, compile your CoffeeScript, run Mocha tests and even update your version number.

Other build tools are available, such as Grunt and, more recently, Broccoli, but I believe Gulp to be superior (see the “Why Gulp?” section below). I’ve compiled a longer list of build tools written in JavaScript.

Gulp is open source and can be found on GitHub.

Installing

Installing is pretty easy. First, install the package globally:

npm install -g gulp

Then, install it in your project:

npm install --save-dev gulp

Using

Let’s create a task to minify one of our JavaScript files. Create a file named gulpfile.js. This is where you will define your Gulp tasks, which will be run using the gulp command.

Put the following in your gulpfile.js file:

var gulp = require('gulp'),

uglify = require('gulp-uglify');

gulp.task('minify', function () {

gulp.src('js/app.js')

.pipe(uglify())

.pipe(gulp.dest('build'))

});

Install gulp-uglify through npm by running npm install –save-dev gulp-uglify, and then run the task by running gulp minify. Assuming that you have a file named app.js in the js directory, a new app.js will be created in the build directory containing the minified contents of js/app.js.

What actually happened here, though?

We’re doing a few things in our gulpfile.js file. First, we’re loading the gulp and gulp-uglify modules:

var gulp = require('gulp'),

uglify = require('gulp-uglify');

Then, we’re defining a task named minify, which, when run, will call the function provided as the second argument:

gulp.task('minify', function () {

});

Finally — and this is where it gets tricky — we’re defining what our task should actually do:

gulp.src('js/app.js')

.pipe(uglify())

.pipe(gulp.dest('build'))

Unless you’re familiar with streams, which most front-end developers are not, the code above won’t mean much to you.

Streams

Streams enable you to pass some data through a number of usually small functions, which will modify the data and then pass the modified data to the next function.

In the example above, the gulp.src() function takes a string that matches a file or number of files (known as a “glob”), and creates a stream of objects representing those files. They are then passed (or piped) to the uglify() function, which takes the file objects and returns new file objects with a minified source. That output is then piped to the gulp.dest() function, which saves the changed files.

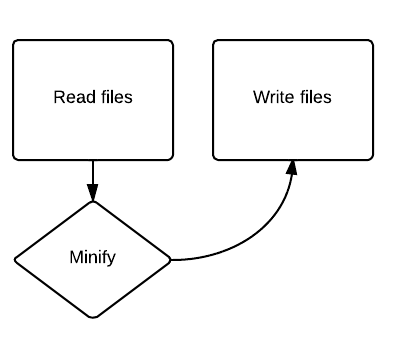

In diagram form, this is what happens:

When there is only one task, the function doesn’t really do much. However, consider the following code:

gulp.task('js', function () {

return gulp.src('js/*.js')

.pipe(jshint())

.pipe(jshint.reporter('default'))

.pipe(uglify())

.pipe(concat('app.js'))

.pipe(gulp.dest('build'));

});

To run this yourself, install gulp, gulp-jshint, gulp-uglify and gulp-concat.

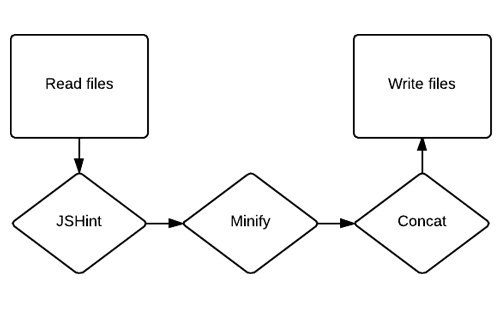

This task will take all files matching js/*.js (i.e. all JavaScript files from the js directory), run JSHint on them and print the output, uglify each file, and then concatenate them, saving them to build/app.js. In diagram form:

If you’re familiar with Grunt, then you’ll notice that this is pretty different to how Grunt does it. Grunt doesn’t use streams; instead, it takes files, runs a single task on them and saves them to new files, repeating the entire process for every task. This results in a lot of hits to the file system, making it slower than Gulp.

For a more comprehensive read on streams, check out the “Stream Handbook.”

gulp.src()

The gulp.src() function takes a glob (i.e. a string matching one or more files) or an array of globs and returns a stream that can be piped to plugins.

Gulp uses node-glob to get the files from the glob or globs you specify. It’s easiest to explain using examples:

js/app.jsMatches the exact filejs/*.jsMatches all files ending in.jsin thejsdirectory onlyjs/**/*.jsMatches all files ending in.jsin thejsdirectory and all child directories!js/app.jsExcludesjs/app.jsfrom the match, which is useful if you want to match all files in a directory except for a particular file*.+(js|css)Matches all files in the root directory ending in.jsor.css

Other features are available, but they’re not commonly used in Gulp. Check out out the Minimatch documentation for more.

Let’s say that we have a directory named js containing JavaScript files, some minified and some not, and we want to create a task to minify the files that aren’t already minified. To do this, we match all JavaScript files in the directory and then exclude all files ending in .min.js:

gulp.src(['js/**/*.js', '!js/**/*.min.js'])

Defining Tasks

To define a task, use the gulp.task() function. When you define a simple task, this function takes two attributes: the task’s name and a function to run.

gulp.task('greet', function () {

console.log('Hello world!');

});

Running gulp greet will result in “Hello world” being printed to the console.

A task may also be a list of other tasks. Suppose we want to define a build task that runs three other tasks, css, js and imgs. We can do this by specifying an array of tasks, instead of the function:

gulp.task('build', ['css', 'js', 'imgs']);

These will be run asynchronously, so you can’t assume that the css task will have finished running by the time js starts — in fact, it probably won’t have. To make sure that a task has finished running before another task runs, you can specify dependencies by combining the array of tasks with the function. For example, to define a css task that checks that the greet task has finished running before it runs, you can do this:

gulp.task('css', ['greet'], function () {

// Deal with CSS here

});

Now, when you run the css task, Gulp will execute the greet task, wait for it to finish, and then call the function that you’ve specified.

Default Tasks

You can define a default task that runs when you just run gulp. You can do this by defining a task named default.

gulp.task('default', function () {

// Your default task

});

Plugins

You can use a number of plugins — over 600, in fact — with Gulp. You will find them listed on the plugins page or by searching gulpplugin on npm. Some plugins are tagged “gulpfriendly”; these aren’t plugins but are designed to work well with Gulp. Be aware when searching directly on npm that you won’t be able to see whether a plugin has been blacklisted (scrolling to the bottom of the plugins page, you will see that many are).

Most plugins are pretty easy to use, have good documentation and are run in the same way (by piping a stream of file objects to it). They’ll then usually modify the files (although some, such as validators, will not) and return the new files to be passed to the next plugin.

Let’s expand on our js task from earlier:

var gulp = require('gulp'),

jshint = require('gulp-jshint'),

uglify = require('gulp-uglify'),

concat = require('gulp-concat');

gulp.task('js', function () {

return gulp.src('js/*.js')

.pipe(jshint())

.pipe(jshint.reporter('default'))

.pipe(uglify())

.pipe(concat('app.js'))

.pipe(gulp.dest('build'));

});

We’re using three plugins here, gulp-jshint, gulp-uglify and gulp-concat. You can see in the README files for the plugins that they’re pretty easy to use; options are available, but the defaults are usually good enough.

You might have noticed that the JSHint plugin is called twice. That’s because the first line runs JSHint on the files, which only attaches a jshint property to the file objects without outputting anything. You can either read the jshint property yourself or pass it to the default JSHint reporter or to another reporter, such as jshint-stylish.

The other two plugins are clearer: the uglify() function minifies the code, and the concat(‘app.js’) function concatenates all of the files into a single file named app.js.

gulp-load-plugins

A module that I find really useful is gulp-load-plugins, which automatically loads any Gulp plugins from your package.json file and attaches them to an object. Its most basic usage is as follows:

var gulpLoadPlugins = require('gulp-load-plugins'),

plugins = gulpLoadPlugins();

You can put that all on one line (var plugins = require(‘gulp-load-plugins’)();), but I’m not a huge fan of inline require calls.

After running that code, the plugins object will contain your plugins, camel-casing their names (for example, gulp-ruby-sass would be loaded to plugins.rubySass). You can then use them as if they were required normally. For example, our js task from before would be reduced to the following:

var gulp = require('gulp'),

gulpLoadPlugins = require('gulp-load-plugins'),

plugins = gulpLoadPlugins();

gulp.task('js', function () {

return gulp.src('js/*.js')

.pipe(plugins.jshint())

.pipe(plugins.jshint.reporter('default'))

.pipe(plugins.uglify())

.pipe(plugins.concat('app.js'))

.pipe(gulp.dest('build'));

});

This assumes a package.json file that is something like the following:

{

"devDependencies": {

"gulp-concat": "~2.2.0",

"gulp-uglify": "~0.2.1",

"gulp-jshint": "~1.5.1",

"gulp": "~3.5.6"

}

}

In this example, it’s not actually much shorter. However, with longer and more complicated Gulp files, it reduces a load of includes to just one or two lines.

Version 0.4.0 of gulp-load-plugins, released in early March, added lazy plugin loading, which improves performance. Plugins are not loaded until you call them, meaning that you don’t have to worry about unused plugins in package.json affecting performance (although you should probably clean them up anyway). In other words, if you run a task that requires only two plugins, it won’t load all of the plugins that the other tasks require.

Watching Files

Gulp has the ability to watch files for changes and then run a task or tasks when changes are detected. This feature is amazingly useful (and, for me, probably Gulp’s single most useful one). You can save your LESS file, and Gulp will turn it into CSS and update the browser without your having to do anything.

To watch a file or files, use the gulp.watch() function, which takes a glob or array of globs (the same as gulp.src()) and either an array of tasks to run or a callback.

Let’s say that we have a build task that turns our template files into HTML, and we want to define a watch task that watches our template files for changes and runs the task to turn them into HTML. We can use the watch function as follows:

gulp.task('watch', function () {

gulp.watch('templates/*.tmpl.html', ['build']);

});

Now, when we change a template file, the build task will run and the HTML will be generated.

You can also give the watch function a callback, instead of an array of tasks. In this case, the callback would be given an event object containing some information about the event that triggered the callback:

gulp.watch('templates/*.tmpl.html', function (event) {

console.log('Event type: ' + event.type); // added, changed, or deleted

console.log('Event path: ' + event.path); // The path of the modified file

});

Another nifty feature of gulp.watch() is that it returns what is known as a watcher. Use the watcher to listen for additional events or to add files to the watch. For example, to both run a list of tasks and call a function, you could add a listener to the change event on the returned watcher:

var watcher = gulp.watch('templates/*.tmpl.html', ['build']);

watcher.on('change', function (event) {

console.log('Event type: ' + event.type); // added, changed, or deleted

console.log('Event path: ' + event.path); // The path of the modified file

});

In addition to the change event, you can listen for a number of other events:

endFires when the watcher ends (meaning that tasks and callbacks won’t be called anymore when files are changed)errorFires when an error occursreadyFires when the files have been found and are being watchednomatchFires when the glob doesn’t match any files

The watcher object also contains some methods that you can call:

watcher.end()Stops thewatcher(so that no more tasks or callbacks will be called)watcher.files()Returns a list of files being watched by thewatcherwatcher.add(glob)Adds files to thewatcherthat match the specified glob (also, accepts an optional callback as a second argument)watcher.remove(filepath)Removes a particular file from thewatcher

Reloading Changes In The Browser

You can get Gulp to reload or update the browser when you — or, for that matter, anything else, such as a Gulp task — changes a file. There are two ways to do this. The first is to use the LiveReload plugin, and the second is to use BrowserSync

LiveReload

LiveReload combines with browser extensions (including a Chrome extension) to reload your browser every time a change to a file is detected. It can be used with the gulp-watch plugin or with the built-in gulp.watch() that I described earlier. Here’s an example from the README file of the gulp-livereload repository:

var gulp = require('gulp'),

less = require('gulp-less'),

livereload = require('gulp-livereload'),

watch = require('gulp-watch');

gulp.task('less', function() {

gulp.src('less/*.less')

.pipe(watch())

.pipe(less())

.pipe(gulp.dest('css'))

.pipe(livereload());

});

This will watch all files matching less/*.less for changes. When a change is detected, it will generate the CSS, save the files and reload the browser.

BrowserSync

An alternative to LiveReload is available. BrowserSync is similar in that it displays changes in the browser, but it has a lot more functionality.

When you make changes to code, BrowserSync either reloads the page or, if it is CSS, injects the CSS, meaning that the page doesn’t need to be refreshed. This is very useful if your website isn’t refresh-resistant. Suppose you’re developing four clicks into a single-page application, and refreshing the page would take you back to the starting page. With LiveReload, you would need to click four times every time you make a change. BrowserSync, however, would just inject the changes when you modify the CSS, so you wouldn’t need to click back.

BrowserSync also synchronizes clicks, form actions and your scroll position between browsers. You could open a couple of browsers on your desktop and another on an iPhone and then navigate the website. The links would be followed on all of them, and as you scroll down the page, the pages on all of the devices would scroll down (usually smoothly, too!). When you input text in a form, it would be entered in every window. And when you don’t want this behavior, you can turn it off.

BrowserSync doesn’t require a browser plugin because it serves your files for you (or proxies them, if they’re dynamic) and serves a script that opens a socket between the browser and the server. This hasn’t caused any problems for me in the past, though.

There isn’t actually a plugin for Gulp because BrowserSync doesn’t manipulate files, so it wouldn’t really work as one. However, the BrowserSync module on npm can be called directly from Gulp. First, install it through npm:

npm install --save-dev browser-sync

Then, the following gulpfile.js will start BrowserSync and watch some files:

var gulp = require('gulp'),

browserSync = require('browser-sync');

gulp.task('browser-sync', function () {

var files = [

'app/**/*.html',

'app/assets/css/**/*.css',

'app/assets/imgs/**/*.png',

'app/assets/js/**/*.js'

];

browserSync.init(files, {

server: {

baseDir: './app'

}

});

});

Running gulp browser-sync would then watch the matching files for changes and start a server that serves the files in the app directory.

The developer of BrowserSync has written about some other things you can do in his BrowserSync + Gulp repository.

Why Gulp?

As mentioned, Gulp is one of quite a few build tools available in JavaScript, and other build tools not written in JavaScript are available, too, including Rake. Why should you choose it?

The two most popular build tools in JavaScript are Grunt and Gulp. Grunt was very popular in 2013 and completely changed how a lot of people develop websites. Thousands of plugins are available for it, doing everything from linting, minifying and concatenating code to installing packages using Bower and starting an Express server. This approach is pretty different from Gulp’s, which has only plugins to perform small individuals tasks that do things with files. Because tasks are just JavaScript (unlike the large object that Grunt uses), you don’t need a plugin; you can just start an Express server the normal way.

Grunt tasks tend to be over-configured, requiring a large object containing properties that you really wouldn’t want to have to care about, while the same task in Gulp might take up only a few lines. Let’s look at a simple gruntfile.js that defines a css task to convert our LESS to CSS and then run Autoprefixer on it:

grunt.initConfig({

less: {

development: {

files: {

"build/tmp/app.css": "assets/app.less"

}

}

},

autoprefixer: {

options: {

browsers: ['last 2 version', 'ie 8', 'ie 9']

},

multiple_files: {

expand: true,

flatten: true,

src: 'build/tmp/app.css',

dest: 'build/'

}

}

});

grunt.loadNpmTasks('grunt-contrib-less');

grunt.loadNpmTasks('grunt-autoprefixer');

grunt.registerTask('css', ['less', 'autoprefixer']);

Compare this to the gulpfile.js file that does the same:

var gulp = require('gulp'),

less = require('gulp-less'),

autoprefix = require('gulp-autoprefixer');

gulp.task('css', function () {

gulp.src('assets/app.less')

.pipe(less())

.pipe(autoprefix('last 2 version', 'ie 8', 'ie 9'))

.pipe(gulp.dest('build'));

});

The gulpfile.js version is considerably more readable and smaller.

Because Grunt hits the file system far more often than Gulp, which uses streams, it is nearly always much faster than Grunt. For a small LESS file, the gulpfile.js file above would usually take about 6 milliseconds. The gruntfile.js would usually take about 50 milliseconds — more than eight times longer. This is a tiny example, but with longer files, the amount of time increases significantly.

Further Reading

- How To Harness The Machines: Being Productive With Task Runners

- Why You Should Stop Installing Your WebDev Environment Locally

- Using A Static Site Generator At Scale: Lessons Learned

- Building Web Software With Make

Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App Register Free Now

Register Free Now