An Ultimate Guide To CSS Pseudo Classes And Pseudo Elements

Hola a todos! (Hello, everyone!)

In my early days of web design, I had to learn things the hard way: trial and error. There was no Smashing Magazine, Can I Use, CodePen or any of the other amazing tools at our disposal today. Having someone show me the ropes of web design, especially on the CSS front, would have been incredibly helpful.

Now that I am far more experienced, I want to share with you in a very friendly, casual, non-dogmatic way a CSS reference guide to pseudo-classes and pseudo-elements.

If you’re an experienced web designer or developer, you must know and have used most of the pseudo-classes and pseudo-elements discussed here. However, I encourage you to check the table of contents; you might not have heard of one or two of them before.

Before diving into the meat and bones, and because this article is about pseudo-classes and pseudo-elements, let’s start with the basics: Have you ever wondered what the word “pseudo” means? If so, here’s a definition from Dictionary.com:

adjective

1. not actually but having the appearance of; pretended; false or spurious; sham.

2. almost, approaching, or trying to be.

Without getting overcomplicated with the W3C’s technical definition, a pseudo-class is basically a phantom state or specific characteristic of an element that can be targeted with CSS. A few common pseudo-classes are :link, :visited, :hover, :active, :first-child and :nth-child. There are more, and we’re going to see them all in a minute.

Also, pseudo-classes are always preceded by a colon (:). Then comes the name of the pseudo-class and sometimes a value in parentheses. :nth-child anyone?

Now, pseudo-elements are like virtual elements that we can treat as regular HTML elements. The thing is that they don’t exist in the document tree or DOM. This means we don’t actually type the pseudo-elements, but rather create them with CSS.

A few common pseudo-elements are :after, :before and :first-letter. We’ll talk about them towards the end of this article.

Single Or Double Colon For Pseudo-Elements?

The short answer is, in most cases, either.

The double colon (::) was introduced in CSS3 to differentiate pseudo-elements such as ::before and ::after from pseudo-classes such as :hover and :active. All browsers support double colons for pseudo-elements except Internet Explorer (IE) 8 and below.

Some pseudo-elements, such as ::backdrop, accept only a double colon, though.

Personally, I use single-colon notation so that my CSS is backwards-compatible with legacy browsers. I use double-colon notation on those pseudo-elements that require it, of course.

You are free to use either; there is really no right or wrong about this.

However, the specification, at the time of writing this article, does recommend using single-colon notation for the reason mentioned above, backwards compatibility:

"Please note that the new CSS3 way of writing pseudo-elements is to use a double colon, eg a::after { … }, to set them apart from pseudo-classes. You may see this sometimes in CSS. CSS3 however also still allows for single colon pseudo-elements, for the sake of backwards compatibility, and we would advise that you stick with this syntax for the time being."In the headings in this article, pseudo-elements that support both a single and double colon will be shown with both notations. Pseudo-elements that support only a double colon will be shown as is.

When (Not) To Use CSS Generated Content

Generating content via CSS is achieved by combining the content CSS property with the :before or :after pseudo-element.

This “content” may be either plain text or a container that we manipulate with CSS to display a graphic shape or decorative element. Here, I’ll be referring to the first type of content, text.

Generated content shouldn’t be used for important copy or text, due to the following reasons:

- It won’t be accessible to some screen readers.

- It won’t be selectable.

- If generated content uses superfluous content for the sake of decoration, screen readers that do support CSS generated content will read it out loud, thus making the UX even worse.

Use CSS generated content for decoration and non-vital information, but make sure it’s properly handled by screen readers, so that people with assistive technology are not distracted. Think “progressive enhancement” when deciding whether to use CSS generated content.

Here on Smashing Magazine, Gabriele Romanato has an awesome article about using CSS generated content.

Experimental Pseudo-Classes And Pseudo-Elements

A pseudo-class or pseudo-element that is experimental means that its specification is not stable or finalized. The syntax and behavior could change down the road.

However, we might be able to use experimental pseudo-classes and pseudo-elements now by applying vendor prefixes. To do this, refer to Can I Use; and some kind of auto-prefixing tool, such as -prefix-free or Autoprefixer, is a must.

In this article, you will see an “experimental” label next to a relevant pseudo-class or pseudo-element’s name.

- :active

- ::after/:after

- ::backdrop (experimental)

- ::before/:before

- :checked

- :default

- :dir (experimental)

- :disabled

- :empty

- :enabled

- :first-child

- ::first-letter/:first-letter

- ::first-line/:first-line

- :first-of-type

- :focus

- :fullscreen (experimental)

- :hover

- :in-range

- :indeterminate

- :invalid

- :lang

- :last-child

- :last-of-type

- :link

- :not

- :nth-child

- :nth-last-child

- :nth-last-of-type

- :nth-of-type

- :only-child

- :only-of-type

- :optional

- :out-of-range

- ::placeholder (experimental)

- :read-only

- :read-write

- :required

- :root

- ::selection

- :scope (experimental)

- :target

- :valid

- :visited

- Bonus content: A Sass mixin for links

All right, everyone, let’s get this show started!

Pseudo-Classes

We’ll begin our discussion of pseudo-classes with those relating to states.

States

A state pseudo-class usually come into play when the user performs an action. An “action” in CSS could also be “no action”, as in the case of a link that hasn’t been visited yet.

Let’s check them out.

:link

The :link pseudo-class represents the “normal” state of links and is used to select links that have not yet been visited. Declaring the :link pseudo-class before all other pseudo-classes in this category is recommended. The order of all four is this: :link, :visited, :hover, :active

a:link {

color: orange;

}

If you use it as follows, it can be omitted:

a {

color: orange;

}

:visited

The :visited pseudo-class is used in links that have been visited. Position :visited pseudo-class second in order (after the :link pseudo-class).

a:visited {

color: blue;

}

:hover

The :hover pseudo-class is used to style an element when the user’s pointer is above it. It doesn’t have to be restricted to links, although that is the most common use case.

It should appear third in order (after the :visited pseudo-class).

a:hover {

color: orange;

}

Demo:

See the Pen CSS :hover pseudo-class by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

:active

The :active pseudo-class is used to style an element that has been “activated” either by a pointing device or by a tap on a touchscreen device. It can also be triggered by the keyboard, just like the :focus pseudo-class.

It works very similarly to :focus, the difference being that the :active pseudo-class is an event that occurs between the mouse button being clicked and being released.

It should appear fourth in order (after the :hover pseudo-class).

a:active {

color: rebeccapurple;

}

:focus

The :focus pseudo-class is used to style an element that has gained focus via a pointing device, from a tap on a touchscreen device or via the keyboard. It’s used a lot in form elements.

a:focus {

color: green;

}

Or:

input:focus {

background: #eee;

}

Bonus Content: A Sass Mixin For Links

If you work with CSS preprocessors, such as Sass, this bonus content might interest you.

(If you’re not into CSS preprocessors — and that’s OK — you can skip to the section on structural pseudo-classes.)

In the spirit of optimizing our workflow, below is a Sass mixin that we can use to create a basic set of links.

The idea behind this mixin is that no defaults are declared in the arguments. So, we are “forced,” in a friendly way, to declare all four states of our links.

The :focus and :active pseudo-classes are usually declared together. Feel free to separate them if you prefer.

Note that this mixin can be applied to any HTML element, not just links.

Here is our mixin:

@mixin links ($link, $visited, $hover, $active) {

& {

color: $link;

&:visited {

color: $visited;

}

&:hover {

color: $hover;

}

&:active, &:focus {

color: $active;

}

}

}

Usage:

a {

@include links(orange, blue, yellow, teal);

}

Compiles to:

a {

color: orange;

}

a:visited {

color: blue;

}

a:hover {

color: yellow;

}

a:active, a:focus {

color: teal;

}

Demo:

See the Pen Sass Mixin for Links by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

Structural

Structural pseudo-classes target additional information in the document tree or DOM and cannot be represented by another type of selectors or combinators.

:first-child

The :first-child pseudo-class represents the first child of its parent element.

In the following example, the first li element will be the only one with orange text.

HTML:

<ul>

<li>This text will be orange.</li>

<li>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</li>

<li>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</li>

</ul>

CSS:

li:first-child {

color: orange;

}

:first-of-type

The :first-of-type pseudo-class represents the first element of its kind in its parent container.

In the following example, the first li element and the first span element will be the only ones with orange text.

HTML:

<ul>

<li>This text will be orange.</li>

<li>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet. <span>This text will be orange.</span></li>

<li>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</li>

</ul>

CSS:

ul :first-of-type {

color: orange;

}

:last-child

The :last-child pseudo-class represents the last child element in its parent container.

In the following example, the last li element will be the only one with orange text.

HTML:

<ul>

<li>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</li>

<li>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</li>

<li>This text will be orange.</li>

</ul>

CSS:

li:last-child {

color: orange;

}

:last-of-type

The :last-of-type pseudo-class represents the last element of its kind in its parent container.

In the following example, the last li and the last span elements will be the only ones with orange text.

HTML:

<ul>

<li>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet. <span>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</span> <span>This text will be orange.</span></li>

<li>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</li>

<li>This text will be orange.</li>

</ul>

CSS:

ul :last-of-type {

color: orange;

}

:not

The :not pseudo-class is also known as the negation pseudo-class. It accepts an argument — basically, another “selector” — inside parentheses. The argument can actually be another pseudo-class.

It may be chained but may not contain another :not selector.

In the following example, the :not pseudo-class matches an element that is not represented by the argument.

HTML:

<ul>

<li class="first-item">Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</li>

<li>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</li>

<li>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</li>

<li>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</li>

</ul>

CSS:

In the following, all text is orange, except the li element with the class of .first-item:

li:not(.first-item) {

color: orange;

}

Now, we’re going to chain two :not pseudo-classes. All elements will have black text and a yellow background, except the li element with the class .first-item and the last li element in the list:

li:not(.first-item):not(:last-of-type) {

background: yellow;

color: black;

}

Demo:

See the Pen CSS :not pseudo-class by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

:nth-child

The :nth-child pseudo-class targets one or more elements depending on their order in the markup.

This pseudo-class is one of the most versatile and robust pseudo-classes in CSS.

All of the :nth pseudo-classes take an argument, which is a formula that we type in parentheses. The formula may be a single integer, a formula structured as an+b or the keyword odd or even.

In the an+b formula:

- the

ais a number (called an integer); - the

nis a literaln(in other words, we will actually type the letternin the formula); - the

+is an operator that may be either a plus sign (+) or a minus sign (-); - the

bis an integer as well but is only required if an operator is being used.

Using the Greek alphabet, here are a few examples using the following basic HTML structure:

<ol>

<li>Alpha</li>

<li>Beta</li>

<li>Gamma</li>

<li>Delta</li>

<li>Epsilon</li>

<li>Zeta</li>

<li>Eta</li>

<li>Theta</li>

<li>Iota</li>

<li>Kappa</li>

</ol>

CSS:

Let’s select the second child. So, only “Beta” will be orange:

ol :nth-child(2) {

color: orange;

}

Now, let’s select every other child starting from the second. So, “Beta,” “Delta,” “Zeta,” “Theta” and “Kappa” will be orange:

ol :nth-child(2n) {

color: orange;

}

Let’s select all even-numbered children:

ol :nth-child(even) {

color: orange;

}

Let’s select every other child, starting from the sixth. So, “Zeta,” “Theta” and “Kappa” will be orange:

ol :nth-child(2n+6) {

color: orange;

}

Demo:

See the Pen CSS :nth-child pseudo-class by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

:nth-last-child

The :nth-last-child pseudo-class basically works the same as :nth-child except that it selects elements starting from the end, rather than the beginning.

CSS:

Let’s select the second child, starting from the end. So, only “Iota” will be orange:

ol :nth-last-child(2) {

color: orange;

}

Now, let’s select every other child, starting with the second from the end. So, “Iota,” “Eta,” “Epsilon,” “Gamma” and “Alpha” will be orange:

ol :nth-last-child(2n) {

color: orange;

}

Let’s select all even children, starting from the end:

ol :nth-last-child(even) {

color: orange;

}

Let’s select every other child, starting with the sixth element from the end. So, “Epsilon,” “Gamma” and “Alpha” will be orange:

ol :nth-last-child(2n+6) {

color: orange;

}

:nth-of-type

The :nth-of-type pseudo-class works basically the same as :nth-child, the main difference being that it’s more specific because we’re targeting a specific element relative to like elements contained within the same parent element.

In the following example, all second paragraphs in any given container will be orange.

HTML:

<article>

<h1>Heading Goes Here</h1>

<p>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</p>

<a href=""><img src="images/rwd.png" alt="Mastering RWD"></a>

<p>This text will be orange.</p>

</article>

CSS:

p:nth-of-type(2) {

color: orange;

}

:nth-last-of-type

The :nth-last-of-type pseudo-class works the same as :nth-of-type, the difference being that it starts counting from the end of the list, rather than the beginning.

In the following example, because we’re starting from the bottom, all first paragraphs will be orange.

HTML:

</article>

</h1>Heading Goes Here</article>/h1>

</p>This text will be orange.</p>

</a href="#"><img src="images/rwd.png" alt="Mastering RWD"></a>

</p>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</p>

</article>

CSS:

p:nth-last-of-type(2) {

color: orange;

}

[](#resources-for-nth)Resources

Refer to these two great resources when working with the :nth pseudo-classes:

- “CSS3 Structural Pseudo-Class Selector Tester,” Lea Verou

- “:nth Tester,” CSS-Tricks

:only-child

The :only-child pseudo-class targets the only child of a parent element.

In the following example, the first ul element has a single child, which will be given orange text. The second ul element has several children; therefore, its children won’t be affected by the :only-child pseudo-class.

HTML:

<ul>

<li>This text will be orange.</li>

</ul>

<ul>

<li>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</li>

<li>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</li>

</ul>

CSS:

ul :only-child {

color: orange;

}

:only-of-type

The :only-of-type pseudo-class targets an element that has no siblings of that particular type. This is similar to :only-child except that we can target a specific element and make the selector more meaningful.

In the following example, the first ul has a single child, which will be given orange text.

HTML:

<ul>

<li>This text will be orange.</li>

</ul>

<ul>

<li>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</li>

<li>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</li>

</ul>

CSS:

li:only-of-type {

color: orange;

}

:target

The :target pseudo-class… well, targets the unique ID of an element and the hash in the URL.

In the following example, the article with the ID of target will be targeted when the URL in the browser ends with #target.

URL:

https://awesomebook.com/#target

HTML:

<article id="target">

<h1><code>:target</code> pseudo-class</h1>

<p>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit!</p>

</article>

CSS:

:target {

background: yellow;

}

Tip: You can use the background: shorthand instead of background-color: to achieve the same result.

Validation

Forms have always been the bane of web design and development. With the help of validation pseudo-classes, we can make the process of filling out forms a smoother and more pleasant experience.

Note, however, that although most of the pseudo-classes listed in this section work well with form elements, some pseudo-classes can be used with other HTML elements, too.

Let’s check out these pseudo-classes!

:checked

The :checked pseudo-class targets radio buttons, checkboxes and option elements that have been checked or selected.

In the following example, when the checkbox is selected, the label is highlighted, thus enhancing the user experience.

Demo:

See the Pen CSS :checked pseudo-class by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

:default

The :default pseudo-class targets the default element in a form among a group of similar elements.

In case you need to target the default button in a form that does not have a class, you can use the :default pseudo-class.

Note that providing a “Reset” or “Clear” button in a form comes with some serious usability issues. Avoid using it unless absolutely necessary. The following articles explain some reasons why:

- “Reset and Cancel Buttons,” Nielsen Norman Group (2000)

- “Killing the Cancel Button on Forms for Good,” UX Movement (2010)

Demo:

See the Pen CSS :default pseudo-class by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

:disabled

The :disabled pseudo-class targets a form element in the disabled state. An element in a disabled state can’t be selected, checked or activated or gain focus.

In the following example, the input for the name field is disabled, so it will be shown as 50% transparent.

HTML:

<input type="text" id="name" disabled>

CSS:

:disabled {

opacity: .5;

}

Tip: Using disabled="disabled" in the markup isn’t required. You can accomplish the same result using only the attribute disabled. Keep in mind, though, that using disabled="disabled" is required in XHTML.

Demo:

See the Pen CSS :disabled pseudo-class by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

:empty

The :empty pseudo-class targets elements that have no content in them of any kind at all. If an element has a letter, another HTML element or even a space, then that element would not be empty.

Here is what is considered empty and not empty:

- Empty

No content or characters would appear in an element. An HTML comment inside an element does not count as content in this case. - Not empty

Characters would appear inside the element. Even a space would be considered content.

In the following example:

- the top container has text, so it will have an orange background;

- the second container has a space, which is considered content, so it will have an orange background as well;

- the third container has nothing in it (it’s empty), so it will have a yellow background;

- the last container has only an HTML comment (it’s empty, too), so it will have a yellow background as well.

HTML:

<div>This box is orange</div>

<div> </div>

<div></div>

<div><!-- This comment is not considered content --></div>

CSS:

div {

background: orange;

height: 30px;

width: 200px;

}

div:empty {

background: yellow;

}

Demo:

See the Pen CSS :empty pseudo-class by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

:enabled

The :enabled pseudo-class targets elements that are enabled. All form elements are enabled by default — that is, until we add the disabled attribute to the element in the markup.

We can use a combination of :enabled and :disabled to provide visual feedback, thus improving the user experience.

In the following example, after having been disabled, the input for name is enabled and so is given an opacity value of 1 and a 1-pixel green border:

:enabled {

opacity: 1;

border: 1px solid green;

}

Tip: Using enabled="enabled" in the markup isn’t required. You can accomplish the same result using only the enabled attribute. Keep in mind, though, that enabled="enabled" is required in XHTML.

Demo:

See the Pen CSS :enabled pseudo-class by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

:in-range

The :in-range pseudo-class targets elements that have a range and whose values are within the defined range.

In the following example, the input element supports a range between 5 and 10. Values within this range will trigger a green border.

HTML:

<input type="number" min="5" max="10">

CSS:

input[type=number] {

border: 5px solid orange;

}

input[type=number]:in-range {

border: 5px solid green;

}

Demo:

See the Pen CSS :in-range and :out-of-range pseudo-classes by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

:out-of-range

The :out-of-range pseudo-class targets elements that have a range and whose values fall outside of the defined range.

In the following example, the input element supports a range between 1 and 12. Values outside of this range will trigger an orange border.

HTML:

<input id="months" name="months" type="number" min="1" max="12">

CSS:

input[type=number]:out-of-range {

border: 1px solid orange;

}

Demo:

See the Pen CSS :in-range and :out-of-range pseudo-classes by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

:indeterminate

The :indeterminate pseudo-class targets input elements such as radio buttons and check boxes that are not selected or that are unselected upon the page loading.

An example of this is when a page loads with a group of radio buttons and no default or preselected radio button has been set, or when a checkbox has been given the indeterminate state via JavaScript.

HTML:

<ul>

<li>

<input type="radio" name="list" id="option1">

<label for="option1">Option 1</label>

</li>

<li>

<input type="radio" name="list" id="option2">

<label for="option2">Option 2</label>

</li>

<li>

<input type="radio" name="list" id="option3">

<label for="option3">Option 3</label>

</li>

</ul>

CSS:

:indeterminate + label {

background: orange;

}

Demo:

See the Pen CSS :indeterminate pseudo-class by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

:valid

The :valid pseudo-class targets a form element whose formatting is correct according to that element’s required format.

In the following example, the email input field has a correctly formatted email structure; so, the field would be considered valid and would appear with a 1-pixel green border:

input[type=email]:valid {

border: 1px solid green;

}

Demo:

See the Pen CSS :valid and :invalid pseudo-classes by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

:invalid

The :invalid pseudo-class targets a form element whose formatting is not correct according to that element’s required format.

In the following example, when the email input field has an incorrectly formatted email structure, the value would be considered invalid, and so an orange border would appear around the field:

input[type=email]:invalid {

background: orange;

}

Demo:

See the Pen CSS :valid and :invalid pseudo-classes by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

:optional

The :optional pseudo-class targets input fields that are not required in a form. In other words, as long as an input doesn’t have the required attribute, it can be targeted with the :optional pseudo-class.

In the following example, the field is optional. It doesn’t have the required attribute, so the text will appear gray.

HTML:

<input type="number">

CSS:

:optional {

color: gray;

}

:read-only

The :read-only pseudo-class targets an element that cannot be edited by the user. It’s similar to the :disabled pseudo-class; the attribute used in the markup would determine which pseudo-class we should use.

This would be useful, for example, in a form where we need to show pre-populated information that cannot be altered but that still needs to be displayed within the form element for submission purposes.

In the following example, the input element has a readonly HTML attribute. So, it can be targeted with the :read-only pseudo-class, which we will use to give it gray text.

HTML:

<input type="text" value="I am read only" readonly>

CSS:

input:read-only {

color: gray;

}

Demo:

See the Pen CSS :read-only pseudo-class by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

:read-write

The :read-write pseudo-class targets elements that can be edited by the user. It can work on elements that have the contenteditable HTML attribute as well.

This pseudo-class can be combined with the :focus pseudo-class to enhance the UX in certain situations.

In the following example, the user would be able to edit the div by clicking on it. We could enhance the user experience by applying a particular style that differentiates this piece of content from the rest, providing a visual cue to the user that this content can be edited.

HTML:

<div class="editable" contenteditable>

<h1>Click on this text to edit it</h1>

<p>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit!</p>

</div>

CSS:

:read-write:focus {

padding: 5px;

border: 1px dotted black;

}

Demo:

See the Pen CSS :read-write pseudo-class by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

:required

The :required pseudo-class targets input elements that have the required HTML attribute.

In addition to relying on the traditional asterisk (*) on an input element’s label to denote that it is required, we could also style the field with CSS. Basically, we get the best of both worlds.

In the following example, the input field has the required HTML attribute. We can enhance the UX by applying a particular style that gives a visual cue that the field is… well, required.

HTML:

<input type="email" required>

CSS:

:required {

color: black;

font-weight: bold;

}

Demo:

See the Pen CSS :required pseudo-class by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

:scope (Experimental)

The :scope pseudo-class makes most sense when it’s tied to the scoped HTML attribute in a style tag.

If there is no scoped attribute in a style tag within a section of the page, then the :scope pseudo-class will traverse all the way up to the html element, which is basically the default scope of a style sheet.

In the following example, the HTML block has a scoped style sheet, and so all text in the second section element will be shown in italics.

HTML and CSS:

<article>

<section>

<h1>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet</h1>

<p>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</p>

</section>

<section>

<style scoped>

:scope {

font-style: italic;

}

</style>

<h1>This text will be italicized</h1>

<p>This text will be italicized.</p>

</section>

</article>

Demo:

See the Pen CSS :scope pseudo-class by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

Language

Language pseudo-classes relate to the text contained on the page. They do not target any media such as images or video.

:dir (Experimental)

The :dir pseudo-class targets an element whose directionality is specified in the document. In other words, in order for the :dir pseudo-class to work, we need to specify the directionality of the relevant element in the markup with the dir HTML attribute.

Two directions are currently available and supported: ltr (left to right) and rtl (right to left).

At the time of writing, only Firefox (with a prefixed -moz-dir() selector) supports the :dir pseudo-class. This will very likely change in future; so, the following examples show both the prefixed and non-prefixed selectors.

Note: Combining the prefixed and unprefixed versions in a single rule won’t work. We need to create two separate rules.

In the following example, the paragraph is written in Arabic (whose script is right to left); so, the text will be orange.

HTML:

<article dir="rtl">

<p>التدليك واحد من أقدم العلوم الصحية التي عرفها الانسان والذي يتم استخدامه لأغراض الشفاء منذ ولاده الطفل.</p>

</article>

CSS:

/* prefixed */

article :-moz-dir(rtl) {

color: orange;

}

/* unprefixed */

article :dir(rtl) {

color: orange;

}

The paragraph in the following example is written in English (left to right); so, the text will be in blue.

HTML:

<article dir="ltr">

<p>If you already know some HTML and CSS and understand the principles of responsive web design, then this book is for you.</p>

</article>

CSS:

/* prefixed */

article :-moz-dir(ltr) {

color: blue;

}

/* unprefixed */

article :dir(ltr) {

color: blue;

}

Demo:

See the Pen CSS :dir pseudo-class by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

:lang

The :lang pseudo-class matches the language of an element as determined by a combination of the lang="" HTML attribute, the corresponding meta element and information gleaned from the protocol, such as an HTTP header.

The lang="" HTML attribute is commonly used in the html tag, but it can also be used in any other tag if needed.

On a tangential note, a common practice is to add proper quotation marks to a particular language using the quotes CSS property. However, the user agents (UA) of most browsers (including IE 9 and up) are able to add proper quotation marks automatically in case they are not declared in the CSS.

Depending on your circumstance, this may or may not be OK, because there are differences between the default quotation marks added by a browser’s UA and the commonly used quotation marks added via CSS.

For example, German (de) quotation marks added by a browser’s UA look like this:

„Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.“

However, in most examples found on the web where quotations marks are declared via CSS, German quotation marks look like this:

»Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.«

Both are actually correct. So, you’ll have to decide whether to let the UA add the quotation marks or to add them yourself via CSS using the :lang pseudo-class and the quotes CSS property.

Let’s add quotation marks with CSS.

HTML:

<article lang="en">

<q>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</q>

</article>

<article lang="fr">

<q>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</q>

</article>

<article lang="de">

<q>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</q>

</article>

CSS:

:lang(en) q { quotes: '“' '”'; }

:lang(fr) q { quotes: '«' '»'; }

:lang(de) q { quotes: '»' '«'; }

Demo:

See the Pen CSS :lang pseudo-class by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

Miscellaneous

Let’s explore some pseudo-classes with other functionality.

:root

The :root pseudo-class refers to the highest parent element in a document.

In virtually all cases, the :root pseudo-class will refer to the html element in an HTML document. However, it could refer to a different element if it’s used in another markup language, such as SVG or XML.

Let’s add a solid background color to the html element, the highest parent element in an HTML document:

:root {

background: orange;

}

Note: We could have accomplished the same effect if we had used html as the selector. However, :root, like a class, has a higher specificity than an element selector (in this case, html).

:fullscreen (Experimental)

The :fullscreen pseudo-class targets elements that are displayed in full-screen mode.

However, it is not intended to work when the user presses F11 to enter full-screen mode in their browser. Rather, it is intended to work with the JavaScript Fullscreen API, which is geared to images, videos and games that are executed in a parent container.

The way to tell whether we have entered full-screen mode is when a message appears at the top of the browser telling us so and when pressing the Escape key takes us back to the normal page. We see this when maximizing a video in YouTube or Vimeo, for example.

If you plan to use the :fullscreen pseudo-class, keep in mind that browsers style things very differently. Plus, you will have to deal with browser prefixes not only in the CSS, but also in your JavaScript. I recommend using Hernan Rajchert’s screenfull.js, which irons out most browser quirks.

The Fullscreen API is beyond the scope of this article, but here’s a snippet that will work in WebKit and Blink browsers.

HTML:

<h1 id="element">This heading will have a solid background color in full-screen mode.</h1>

<button onclick="var el = document.getElementById('element'); el.webkitRequestFullscreen();">Trigger full screen!</button>

CSS:

h1:fullscreen {

background: orange;

}

Demo:

See the Pen CSS :fullscreen pseudo-class by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

Pseudo-Elements

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, pseudo-elements are like virtual elements that we can treat like regular HTML elements. They don’t exist in the document tree or DOM, which means we don’t actually type pseudo-elements in the HTML, but rather create them with CSS.

Also, the double colon (::) and single colon (:) difference is merely a visual distinction between CSS 2.1 and CSS3 pseudo-elements. You are free to use either.

::before/:before

The :before pseudo-element, like its sibling :after, adds content (text or a shape) to another HTML element. Again, this content is not actually present in the DOM but can be manipulated as if it were. And the content property needs to be declared in the CSS.

Remember that text added with this pseudo-element cannot be selected.

HTML:

<h1>Ricardo</h1>

CSS:

h1:before {

content: "Hello "; /* Note the space after the word Hello. */

}

This will render like so:

Hello Ricardo!

Note: See the space after the word “Hello ”? Yes, spaces are taken into account.

::after/:after

The :after pseudo-element is used to add content (either text or a shape) to another HTML element. This content is not actually present in the DOM, but it can be manipulated as if it were. In order for it to work, the content property needs to be declared in the CSS.

Note that any text added with this pseudo-class cannot be selected.

HTML:

<h1>Ricardo</h1>

CSS:

h1:after {

content: ", Web Designer!";

}

This will render like so:

Ricardo, Web Designer!

::backdrop (Experimental)

The ::backdrop pseudo-element is a box that is generated behind the full-screen element but that sits above all other content. It’s used in combination with the :fullscreen pseudo-class to change the background color of a maximized screen — in case you don’t want to go with the default black.

Note: The ::backdrop pseudo-element requires a double colon; it doesn’t work with a single colon.

Let’s continue our example from the :fullscreen pseudo-class.

HTML:

<h1 id="element">This heading will have a solid background color in full-screen mode.</h1>

<button onclick="var el = document.getElementById('element'); el.webkitRequestFullscreen();">Trigger full screen!</button>

CSS:

h1:fullscreen::backdrop {

background: orange;

}

Demo:

See the Pen CSS ::backdrop pseudo-element by Ricardo Zea(@ricardozea) on CodePen.

::first-letter/:first-letter

The :first-letter pseudo-element selects the first letter in a line of text.

If an element is included before that line, such as an image, video or table, then the first letter is not affected and can still be selected.

This is a great feature to use in paragraphs, for example, to enhance typographic appeal, without having to resort to an image or external assets.

Tip: For text generated with the :before pseudo-element, the first letter of that text will be targeted, even though it is not present in the DOM.

CSS:

h1:first-letter {

font-size: 5em;

}

::first-line/:first-line

The :first-line pseudo-element targets the first line of an element. It works only on block-level elements, not inline elements.

When used in a paragraph, for example, only the first line of that paragraph will be styled, even if the text wraps.

CSS:

p:first-line {

background: orange;

}

::selection

The ::selection pseudo-element is used to style the portion of a document that has been highlighted.

Until further notice, Gecko-based browsers required the prefixed version: ::-moz-selection.

Note: Combining the prefixed and unprefixed versions in a single rule won’t work. We need to create two separate rules.

CSS:

::-moz-selection {

color: orange;

background: #333;

}

::selection {

color: orange;

background: #333;

}

::placeholder (Experimental)

The ::placeholder pseudo-element targets placeholder text used in form elements via the placeholder HTML attribute.

It can also be written as ::input-placeholder, which is actually the syntax used in CSS.

Note: This pseudo-element is not a part of the standard and its implementation will very likely change in future, so use with caution.

In some browsers (IE 10 and Firefox up to version 18), the ::placeholder pseudo-element is implemented like a pseudo-class. All other browsers treat it like a pseudo-element. So, unless you have to support old versions of Firefox or IE 10, you would write the following.

HTML:

<input type="email" placeholder="name@domain.com">

CSS:

input::-moz-placeholder {

color:#666;

}

input::-webkit-input-placeholder {

color:#666;

}

/* IE 10 only */

input:-ms-input-placeholder {

color:#666;

}

/* Firefox 18 and below */

input:-moz-input-placeholder {

color:#666;

}

Conclusion

Phew! That was something, eh?

CSS pseudo-classes and pseudo-elements are certainly a handful, aren’t they? They provide so many possibilities that one can easily feel overwhelmed, for sure. But that’s the life of a web designer and developer.

Make sure to test thoroughly. Well implemented pseudo-classes and pseudo-elements go a long way.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this extensive reference article as much as I did writing it. And don’t forget to bookmark it!

Thank you for reading! Hasta la próxima! (Until next time!)

Further Reading

- Learning To Use The :before And :after Pseudo-Elements In CSS

- Take Your Design To The Next Level With CSS3

- CSS3 Flexible Box Layout

- Getting Started With Neon Branching

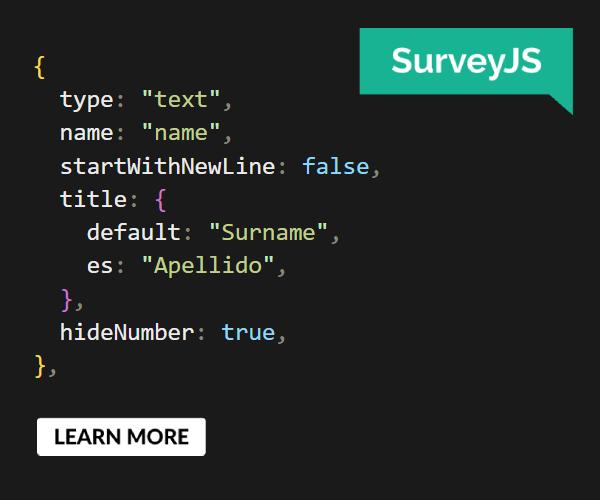

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App Register now for WAS 2026

Register now for WAS 2026

Register for free to attend Axe-con

Register for free to attend Axe-con