HTML APIs: What They Are And How To Design A Good One

As JavaScript developers, we often forget that not everyone has the same knowledge as us. It’s called the curse of knowledge: When we’re an expert on something, we cannot remember how confused we felt as newbies. We overestimate what people will find easy.

Therefore, we think that requiring a bunch of JavaScript to initialize or configure the libraries we write is OK. Meanwhile, some of our users struggle to use them, frantically copying and pasting examples from the documentation, tweaking them at random until they work.

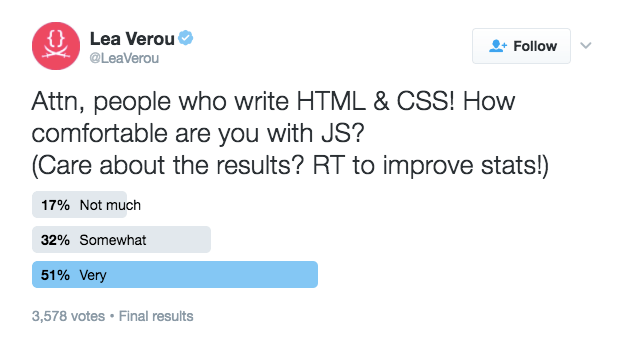

You might be wondering, “But all HTML and CSS authors know JavaScript, right?” Wrong. Take a look at the results of my poll, which is the only data on this I’m aware of. (If you know of any proper studies on this, please mention them in the comments!)

One in two people who write HTML and CSS is not comfortable with JavaScript. One in two. Let that sink in for a moment.

As an example, look at the following code to initialize a jQuery UI autocomplete, taken from its documentation:

<div class="ui-widget">

<label for="tags">Tags: </label>

<input id="tags">

</div>

$( function() {

var availableTags = [

"ActionScript",

"AppleScript",

"Asp",

"BASIC",

"C"

];

$( "#tags" ).autocomplete({

source: availableTags

});

} );

This is easy, even for people who don’t know any JavaScript, right? Wrong. A non-programmer would have all sorts of questions going through their head after seeing this example in the documentation. “Where do I put this code?” “What are these braces, colons and brackets?” “Do I need them?” “What do I do if my element does not have an ID?” And so on. Even this tiny snippet of code requires people to understand object literals, arrays, variables, strings, how to get a reference to a DOM element, events, when the DOM is ready and much more. Things that seem trivial to programmers can be an uphill battle to HTML authors with no JavaScript knowledge.

Now consider the equivalent declarative code from HTML5:

<div class="ui-widget">

<label for="tags">Tags: </label>

<input id="tags" list="languages">

<datalist id="languages">

<option>ActionScript</option>

<option>AppleScript</option>

<option>Asp</option>

<option>BASIC</option>

<option>C</option>

</datalist>

</div>

Not only is this much clearer to anyone who can write HTML, it is even easier for programmers. We see that everything is set in one place, no need to care about when to initialize, how to get a reference to the element and how to set stuff on it. No need to know which function to call to initialize or which arguments it accepts. And for more advanced use cases, there is also a JavaScript API in place that allows all of these attributes and elements to be created dynamically. It follows one of the most basic API design principles: It makes the simple easy and the complex possible.

This brings us to an important lesson about HTML APIs: They would benefit not only people with limited JavaScript skill. For common tasks, even we, programmers, are often eager to sacrifice the flexibility of programming for the convenience of declarative markup. However, we somehow forget this when writing a library of our own.

So, what is an HTML API? According to Wikipedia, an API (or application programming interface) is “is a set of subroutine definitions, protocols, and tools for building application software.” In an HTML API, the definitions and protocols are in the HTML itself, and the tools look in HTML for the configuration. HTML APIs usually consist of certain class and attribute patterns that can be used on existing HTML. With Web Components, even custom element names are game, and with the Shadow DOM, those can even have an entire internal structure that is hidden from the rest of the page’s JavaScript or CSS. But this is not an article about Web Components; Web Components give more power and options to HTML API designers; but the principles of good (HTML) API design are the same.

HTML APIs improve collaboration between designers and developers, lift some work from the shoulders of the latter, and enable designers to create much higher-fidelity mockups. Including an HTML API in your library does not just make the community more inclusive, it also ultimately comes back to benefit you, the programmer.

Not every library needs an HTML API. HTML APIs are mostly useful in libraries that enable UI elements such as galleries, drag-and-drop, accordions, tabs, carousels, etc. As a rule of thumb, if a non-programmer cannot understand what your library does, then your library doesn’t need an HTML API. For example, libraries that simplify or help to organize code do not need an HTML API. What kind of HTML API would an MVC framework or a DOM helper library even have?

So far, we have discussed what an HTML API is, why it is useful and when it is needed. The rest of this article is about how to design a good one.

Init Selector

With a JavaScript API, initialization is strictly controlled by the library’s user: Because they have to manually call a function or create an object, they control precisely when it runs and on what. With an HTML API, we have to make that choice for them, and make sure not to get in the way of the power users who will still use JavaScript and want full control.

The common way to resolve the tension between these two use cases is to only auto-initialize elements that match a given selector, usually a specific class. Awesomplete follows this approach, only picking up input elements with class=“awesomplete”.

In some cases, making auto-initialization easy is more important than making opt-in explicit. This is common when your library needs to run on a lot of elements, and when avoiding having to manually add a class to every single one is more important than making opt-in explicit. For example, Prism automatically highlights any <code> element that contains a language-xxx class (which is what the HTML5 specification recommends for specifying the language of a code snippet) or that is inside an element that does. This is because it could be included in a blog with a ton of code snippets, and having to go back and add a class to every single one of them would be a huge hassle.

In cases where the init selector is used very liberally, a good practice is to allow customization of it or allow opting-out of auto-initialization altogether. For example, Stretchy autosizes every <input>, <select> and <textarea> by default, but allows customization of its init selector to something more specific via a data-stretchy-filter attribute. Prism supports a data-manual attribute on its <script> element to completely disable automatic initialization. A good practice is to allow this option to be set via either HTML or JavaScript, to accommodate both types of library users.

Minimize Init Markup

So, for every element the init selector matches, your library needs a wrapper around it, three buttons inside it and two adjacent divs? No problem, but generate them yourself. This kind of grunt work is better suited to machines, not humans. Do not expect that everyone using your library is also using some sort of templating system: Many people are still hand-crafting markup and find build systems too complicated. Make their lives easier.

This also minimizes error conditions: What if a user includes the class that you expect for initialization but not all of the markup you need? When there is no extra markup to add, no such errors are possible.

There is one exception to this rule: graceful degradation and progressive enhancement. For example, embedding a tweet involves a lot of markup, even though a single element with data-* attributes for all the options would suffice. This is done so that the tweet is readable even before the JavaScript loads or runs. A good rule of thumb is to ask yourself, does the extra markup offer a benefit to the end user even without JavaScript? If so, then requiring it is OK. If not, then generate it with your library.

There is also the classic tension between ease of use and customization: Generating all of the markup for the library’s user is easier for them, but leaving them to write it gives them more flexibility. Flexibility is great when you need it, but annoying when you don’t, and you still have to set everything manually. To balance these two needs, you can generate the markup you need if it doesn’t already exist. For example, suppose you wrap all .foo elements with a .foo-container element? First, check whether the parent — or, better yet, any ancestor, via element.closest(".foo-container") — of your .foo element already has the foo-container class, and if so, use that instead of creating a new element.

Settings

Typically, settings should be provided via data-* attributes on the relevant element. If your library adds a ton of attributes, then you might want to namespace them to prevent collisions with other libraries, like data-foo-* (where foo is a one-to-three letter prefix based on your library’s name). If that’s too long, you could use foo-*, but bear in mind that this will break HTML validation and might put some of the more diligent HTML authors off your library because of it. Ideally, you should support both, if it won’t bloat your code too much. None of the options here are ideal, so there is an ongoing discussion in the WHATWG about whether to legalize such prefixes for custom attributes.

Follow the conventions of HTML as much as possible. For example, if you use an attribute for a boolean setting, its presence means true regardless of the value, and its absence means false. Do not expect things like data-foo="true" or data-foo="false" instead. Sure, ARIA does that, but if ARIA jumped off a cliff, would you do it, too?

When the setting is a boolean, you could also use classes. Typically, their semantics are similar to boolean attributes: The presence of the class means true, and the absence means false. If you want the opposite, you can use a no- prefix (for example, no-line-numbers). Keep in mind that class names are used more than data-* attributes, so there is a greater possibility of collision with the user’s existing class names. You could consider prefixing your classes with a prefix like foo- to prevent that. Another danger with class names is that a future maintainer might notice that they are not used in the CSS and remove them.

When you have a group of related boolean settings, using one space-separated attribute might be better than using many separate attributes or classes. For example, <div data-permissions="read add edit delete save logout>" is better than <div data-read data-add data-edit data-delete data-save data-logout">, and <div class="read add edit delete save logout"> would likely cause a ton of collisions. You can then target individual ones via the ~= attribute selector. For example, element.matches("[data-permissions~=read]") checks whether an element has the read permission.

If the type of a setting is an array or object, then you can use a data-* attribute that links to another element. For example, look at how HTML5 does autocomplete: Because autocomplete requires a list of suggestions, you use an attribute to link to a <datalist> element containing these suggestions via its ID.

This is a point when following HTML conventions becomes painful: In HTML, linking to another element in an attribute is always done by referencing its ID (think of <label for="…">). However, this is rather limiting: It’s so much more convenient to allow selectors or even nesting if it makes sense. What you go with will largely depend on your use case. Just keep in mind that, while consistency is important, usability is our goal here.

It’s OK if not every single setting is available via HTML. Settings whose values are functions can stay in JavaScript and be considered “advanced customization.” Consider Awesomplete: All numerical, boolean, string and object settings are available as data-* attributes (list, minChars, maxItems, autoFirst). All function settings are only available in JavaScript (filter, sort, item, replace, data). If someone is able to write a JavaScript function to configure your library, then they can use the JavaScript API.

Regular expressions (regex) are a bit of a gray area: Typically, only programmers know regular expressions (and even programmers have trouble with them!); so, at first glance there doesn’t seem to be any point in including settings with regex values in your HTML API. However, HTML5 did include such a setting (<input pattern="regex">), and I believe it was quite successful, because non-programmers can look up their use case in a regex directory and copy and paste.

Inheritance

If your UI library is going to be used once or twice on each page, then inheritance won’t matter much. However, if it could be applied to multiple elements, then configuring the same settings on each one of them via classes or attributes would be painful. Remember that not everyone uses a build system, especially non-developers. In these cases, it might be useful to define that settings can be inherited from ancestor elements, so that multiple instances can be mass-configured.

Take Prism, a popular syntax-highlighting library, used here on Smashing Magazine as well. The highlighting language is configured via a class of the form language-xxx. Yes, this goes against the guidelines we discussed in the previous section, but this was a conscious decision because the HTML5 specification recommends this for specifying the language of a code snippet. On a page with multiple code snippets (think of how often a blog post about code uses inline <code> elements!), specifying the coding language on each <code> element would become extremely tedious. To mitigate this pain, Prism supports inheritance of these classes: If a <code> element does not have a language-xxx class of its own, then the one of its closest ancestor that does is used. This enables users to set the coding language globally (by putting the class on the <body> or <html> elements) or by section, and override it only on elements or sections with a different language.

Now that CSS variables are supported by every browser, they are a good candidate for such settings: They are inherited by default and can be set inline via the style attribute, via CSS or via JavaScript. In your code, you get them via getComputedStyle(element).getPropertyValue(“–variablename”). Besides browser support, their main downside is that developers are not yet used to them, but that is changing. Also, you cannot monitor changes to them via MutationObserver, like you can for elements and attributes.

Global Settings

Most UI libraries have two groups of settings: settings that customize how each instance of the widget behaves, and global settings that customize how the library behaves. So far, we have mainly discussed the former, so you might be wondering what is a good place for these global settings.

One candidate is the <script> element that includes your library. You can get this via document.currentScript, and it has very good browser support. The advantage of this is that it’s unambiguous what these settings are for, so their names can be shorter (for example, data-filter, instead of data-stretchy-filter).

However, the <script> element should not be the only place you pick up these settings from, because some users may be using your library in a CMS that does not allow them to customize <script> elements. You could also look for the setting on the <html> and <body> elements or even anywhere, as long as you have a clearly stated policy about which value wins when there are duplicates. (The first one? The last one? Something else?)

Documentation

So, you’ve taken care to design a nice declarative API for your library. Well done! However, if all of your documentation is written as if the user understands JavaScript, few will be able to use it. I remember seeing a cool library for toggling the display of elements based on the URL, via HTML attributes on the elements to be toggled. However, its nice HTML API could not be used by the people it targeted because the entire documentation was littered with JavaScript references. The very first example started with, “This is equivalent to location.href.match(/foo/).” What chance does a non-programmer have to understand this?

Also, remember that many of these people do not speak any programming language, not just JavaScript. Do not talk about models, views, controllers or other software engineering concepts in text that you expect them to read and understand. All you will achieve is confusing them and turning them away.

Of course, you should document the JavaScript parts of your API as well. You could do that in an “Advanced usage” section. However, if you start your documentation with references to JavaScript objects and functions or software engineering concepts, then you’re essentially telling non-programmers that this library is not for them, thereby excluding a large portion of your potential users. Sadly, most documentation for libraries with HTML APIs suffers from these issues, because HTML APIs are often seen as a shortcut for programmers, not as a way for non-programmers to use these libraries. Hopefully, this will change in the future.

What About Web Components?

In the near future, the Web Components quartet of specifications will revolutionize HTML APIs. The <template> element will enable authors to provide scripts with partial inert markup. Custom elements will enable much more elegant init markup that resembles native HTML. HTML imports will enable authors to include just one file, instead of three style sheets, five scripts and ten templates (if Mozilla gets its act together and stops thinking that ES6 modules are a competing technology). The Shadow DOM will enable your library to have complex DOM structures that are properly encapsulated and that do not interfere with the user’s own markup.

However, <template> aside, browser support for the other three is currently limited. So, they require large polyfills, which makes them less attractive for library use. However, it’s something to keep on your radar for the near future.

Further Reading

- Designing Flexible, Maintainable Pie Charts With CSS And SVG

- Accessibility APIs: A Key To Web Accessibility

- Taking Pattern Libraries To The Next Level

- CSS Scroll Snapping Aligned With Global Page Layout: A Full-Width Slider Case Study

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

Register Free Now

Register Free Now

Register for free to attend Axe-con

Register for free to attend Axe-con Register now for WAS 2026

Register now for WAS 2026 Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers