When Your Code Has To Work: Complying With Legal Mandates

Douglas Crockford famously declared browsers to be “the most hostile software engineering environment imaginable,” and that wasn’t hyperbole. Ensuring that our websites work across a myriad of different devices, screen sizes and browsers our users depend on to access the web is a tall order, but it’s necessary.

If our websites don’t enable users to accomplish the key tasks they come to do, we’ve failed them. We should do everything in our power to ensure our websites function under even the harshest of scenarios, but at the same, we can’t expect our users to have the exact same experience in every browser, on every device. Yahoo realized this more than a decade ago and made it a central concept in its “Graded Browser Support” strategy:

"Support does not mean that everybody gets the same thing. Expecting two users using different browser software to have an identical experience fails to embrace or acknowledge the heterogeneous essence of the Web. In fact, requiring the same experience for all users creates an artificial barrier to participation. Availability and accessibility of content should be our key priority."

And that was a few years before the iPhone was introduced!

Providing alternate experience pathways for our core functionality should be a no-brainer, but when it comes to implementing stuff we’d rather not think about, we often reach for the simplest drop-in solution, despite the potential negative impact it could have on our business.

Consider the EU’s “cookie law.” If you’re unfamiliar, this somewhat contentious law is privacy legislation that requires websites to obtain consent from visitors before storing or retrieving information from their device. We call it the cookie law, but the legislation also applies to web storage, IndexedDB and other client-side data storage and retrieval APIs.

Compliance with this law is achieved by:

- Notifying users that the website requires the ability to store and read information on their device;

- Providing a link to the website’s privacy statement, which includes information about the storage mechanisms being used and what they are being used for;

- Prompting users to confirm their acceptance of this requirement.

If you operate a website aimed at folks living in the EU and fail to do this, you could be subject to a substantial fine. You could even open yourself up to a lawsuit.

If you’ve had to deal with the EU cookie law before, you’re probably keenly aware that a ton of “solutions” are available to provide compliance. Those quotation marks are fully intentional because nearly every one I found — including the one provided by the EU itself — has been a drop-in JavaScript file that enables compliance. If we’re talking about the letter of the law, however, they don’t actually. The problem is that, as awesome and comprehensive as some of these solutions are, we can never be guaranteed that our JavaScript programs will actually run. In order to truly comply with the letter of the law, we should provide a fallback version of the utility — just in case. Most people will never see it, but at least we know we’re covered if something goes wrong.

I stumbled into this morass while building the 10k Apart contest website. We weren’t using cookies for much on the website — mainly analytics and vote-tracking — but we were using the Web Storage API to speed up the performance of the website and to save form data temporarily while folks were filling out the form. Because the contest was open to folks who live in the EU, we needed to abide by the cookie law. And because none of the solutions I found actually complied with the law in either spirit or reality — the notable exception being WordPress’ EU Cookie Law plugin, which works both with and without JavaScript, but the contest website wasn’t built in Wordpress or even PHP, so I had to do something else — I opted to roll my own robust solution.

Planning It Out

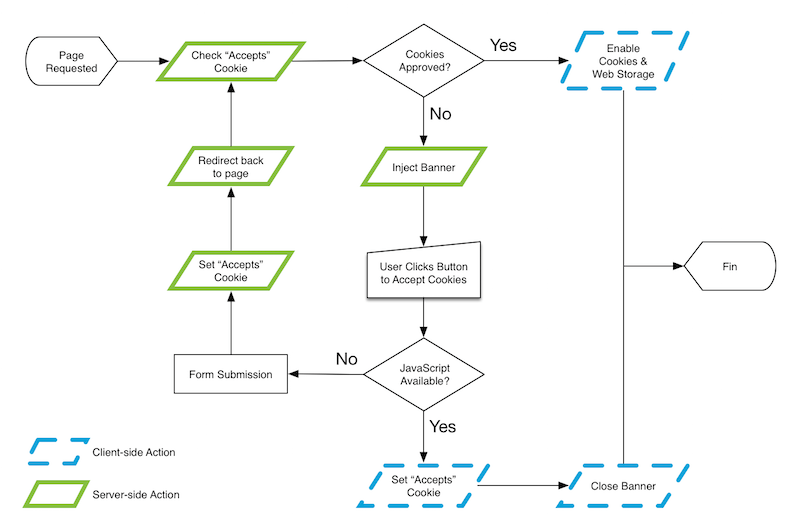

I’m a big fan of using interface experience (IX) maps to diagram functionality. I find their simple nature easy to understand and to tweak as I increase the fidelity of an experience. For this feature, I started with a (relatively) simple IX map that diagrammed what would happen when a user requests a page on the website.

This IX map outlines several potential experiences that vary based on the user’s choice and feature availability. I’ll walk through the ideal scenario first:

- A user comes to the website for the first time. The server checks to see whether they have accepted the use of cookies and web storage but doesn’t find anything.

- The server injects a banner into the HTML, containing the necessary messaging and a form that, when submitted, confirms acceptance.

- The browser renders the page with the banner.

- The user clicks to accept the use of cookies and web storage.

- Client-side JavaScript sets the

acceptscookie and closes the banner. - On subsequent page requests, the server reads the

acceptscookie and does not inject the banner code. JavaScript sees the cookie and enables the cookie and web storage code.

For the vast majority of users, this is the experience they’ll get, and that’s awesome. That said, however, we can never be 100% guaranteed our client-side JavaScript code will run, so we need a backup plan. Here’s the fallback experience:

- A user comes to the website for the first time. The server checks to see whether they have accepted the use of cookies and web storage but doesn’t find anything.

- The server injects a banner into the HTML, containing the necessary messaging and a form that, when submitted, confirms acceptance.

- The browser renders the page with the banner.

- The user clicks to accept the use of cookies and web storage.

- The click initiates a form post to the server, which responds by setting the

acceptscookie before redirecting the user back to the page they were on. - On subsequent page requests, the server reads the

acceptscookie and does not inject the banner code. - If JavaScript becomes available later, it will see the cookie and enable its cookie and web storage code.

Not bad. There’s an extra roundtrip to the server, but it’s a quick one, and, more importantly, it provides a foolproof fallback in the absence of our preferred JavaScript-driven option. True, it could fall victim to a networking issue, but there’s not much we can do to mitigate that without JavaScript in play.

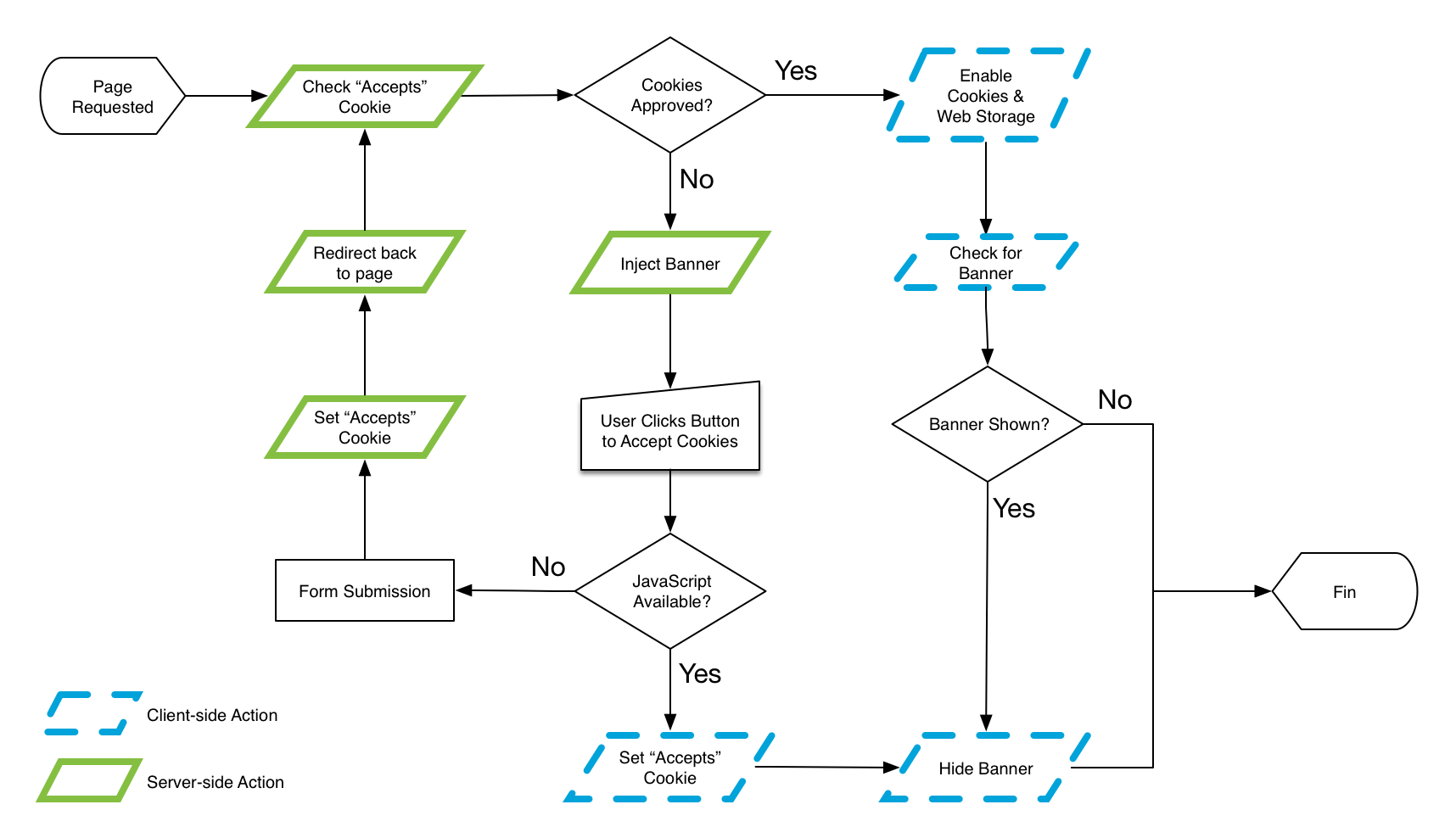

Speaking of mitigating networking issues, the 10k Apart contest website uses a service worker to do some pretty aggressive caching; the service worker intercepts any page request and supplies a cached version if one exists. That could result in users getting a copy of the page with the banner still in it, even if they’ve already agreed to allow cookies. Time to update the IX map.

This is one of the reasons I like IX maps so much: They are really easy to generate and simple to update when you want to add features or handle more scenarios. With a few adjustments in place, I can account for the scenario in which a stale page includes the banner unnecessarily and have JavaScript remove it.

With this plan in place, it was time to implement it.

Server-Side Implementation

10k Apart’s back end is written in Node.js and uses Express. I’m not going to get into the nitty-gritty of our installation and configuration, but I do want to talk about how I implemented this feature. First off, I opted to use Express’ cookie-parser middleware to let me get and set the cookie.

// enable cookie-parser for Express

var cookieParser = require('cookie-parser');

app.use(cookieParser());Once that was set up, I created my own custom Express middleware that would intercept requests and check for the approves_cookies cookie:

var checkCookie = function(req, res, next) {

res.locals.approves_cookies = ( req.cookies['approves_cookies'] === 'yes' );

res.locals.current_url = req.url || '/';

next();

};This code establishes a middleware function named checkCookie(). All Express middleware gets access to the request (req), the response (res) and the next middleware function (next), so you’ll see those accounted for as the three arguments to that function. Then, within the function, I am modifying the response object to include two local variables (res.locals) to capture whether the cookie has already been set (res.locals.approves_cookies) and the currently requested URL (res.locals.current_url). Then, I call the next middleware function.

With that written, I can include this middleware in Express:

app.use(checkCookie);All of the templates for the website are Mustache files, and Express automatically pipes res.locals into those templates. Knowing that, I created a Mustache partial to handle the banner:

{{^approves_cookies}}

<div id="cookie-banner" role="alert">

<form action="/cookies-ok" method="post">

<input type="hidden" name="redirect_to" value="{{current_url}}">

<p>This site uses cookies for analytics and to track voting. If you're interested, more details can be found in <a href="{{privacy_url}}#maincookiessimilartechnologiesmodule">our cookie policy</a>.</p>

<button type="submit">I'm cool with that</button>

</form>

</div>

{{/approves_cookies}}

This template uses an inverted section that only renders the div when approves_cookies is false. Within that markup, you can also see the current_url getting piped into a hidden input to indicate where a user should be redirected if the form method of setting the cookie is used. You remembered: the fallback.

Speaking of the fallback, since we have one, we also need to handle that on the server side. Here’s the Node.js code for that:

var affirmCookies = function (req, res) {

if ( ! req.cookies['approves_cookies'] )

{

res.cookie('approves_cookies', 'yes', {

secure: true,

maxAge: ( 365 * 24 * 60 * 60 ) // 1 year

});

}

res.redirect(req.body.redirect_to);

};

app.post('/cookies-ok', affirmCookies);This ensures that if the form is submitted, Express will respond by setting the approves_cookies cookie (if it’s not already set) and then redirecting the user to the page they were on. Taken altogether, this gives us a solid baseline experience for every user.

Now, it’s worth noting that none of this code is going to be useful to you if your projects don’t involve the specific stack I was working with on this project (Node.js, Express, Mustache). That said, the logic I’ve outlined here and in the IX map is portable to pretty much any language or framework you happen to know and love.

OK, let’s switch gears and work some magic on the front end.

Front-End Implementation

When JavaScript is available and running properly, we’ll want to take full advantage of it, but it doesn’t make sense to run any code against the banner if it doesn’t exist, so first things first: I should check to see whether the banner is even in the page.

var $cookie_banner = document.getElementById('cookie-banner');

if ( $cookie_banner )

{

// actual code will go here

}In order to streamline the application logic, I’m going to add another conditional within to check for the accepts_cookies cookie. I know from my second pass on the IX map there’s an outside chance that the banner might be served up by my service worker even if the accepts cookie exists, so checking for the cookie early lets me run only the bit of JavaScript that removes the banner. But before I jump into all of that, I’ll create a function I can call in any of my code to let me know whether the user has agreed to let me cookie them:

function cookiesApproved(){

return document.cookie.indexOf('approves_cookies') > -1;

}I need this check in multiple places throughout my JavaScript, so it makes sense to break it out into a separate function. Now, let’s revisit my banner-handling logic:

var $cookie_banner = document.getElementById('cookie-banner');

if ( $cookie_banner )

{

// banner exists but cookie is set

if ( cookiesApproved() )

{

// hide the banner immediately!

}

// cookie has not been set

else

{

// add the logic to set the cookie

// and close the banner

}

}Setting cookies in JavaScript is a little convoluted because you need to set it as a string, but it’s not too ghastly. I broke out the process into its own function so that I could set it as an event handler on the form:

function approveCookies( e ) {

// prevent the form from submitting

e.preventDefault();

var cookie, // placeholder for the cookie

expires = new Date(); // start building expiry date

// expire in one year

expires.setFullYear( expires.getFullYear() + 1 );

// build the cookie

cookie = [

'approves_cookies=yes',

'expires=' + expires.toUTCString(),

'domain=' + window.location.hostname,

window.location.protocol == 'https:' ? 'secure' : ''

];

// set it

document.cookie = cookie.join('; ');

// close up the banner

closeCookieBanner();

// return

return false;

};

// find the form inside the banner

var $form = $cookie_banner.getElementsByTagName('form')[0];

// hijack the submit event

$form.addEventListener( 'submit', approveCookies, false );The comments in the code should make it pretty clear, but just in case, here’s what I’m doing:

- Hijack the form submission event (

e) and cancel its default action usinge.preventDefault(). - Use the

Dateobject to construct a date one year out. - Assemble the bits of the cookie, including the

approves_cookiesvalue, the expiry date, the domain the cookie is bound to, and whether the cookie should be secure (so I can test locally). - Set

document.cookieequal to the assembled cookie string. - Trigger a separate method —

closeCookieBanner()— to close the banner (which I will cover in a moment).

With that in place, I can define closeCookieBanner() to handle, well, closing up the banner. There are actually two instances in which I need this functionality: after setting the cookie (as we just saw) and if the service worker serves up a stale page that still has the banner in it. Even though each requires roughly the same functionality, I want to make the stale-page cleanup version a little more aggressive. Here’s the code:

function closeCookieBanner( immediate ) {

// How fast to close? Animation takes .5s

var close_speed = immediate ? 0 : 600;

// remove

window.setTimeout(function(){

$cookie_banner.parentNode.removeChild( $cookie_banner );

// remove the DOM reference

$cookie_banner = null;

}, close_speed);

// animate closed

if ( ! immediate ) {

$cookie_banner.className = 'closing';

}

}This function takes a single optional argument. If true (or anything “truthy”) is passed in, the banner is immediately removed from the page (and its reference is deleted). If no argument is passed in, that doesn’t happen for 0.6 seconds, which is 0.1 seconds after the animation finishes up (we’ll get to the animation momentarily). The class change triggers that animation.

You already saw one instance of this function referenced in the previous code block. Here it is in the cached template branch of the conditional you saw earlier:

…

// banner exists but cookie is set

if ( cookiesApproved() )

{

// close immediately

closeCookieBanner( true );

}

…Adding Some Visual Sizzle

Because I brought up animations, I’ll discuss the CSS I’m using for the cookie banner component, too. Like most implementations of cookie notices, I opted for a visual full-width banner. On small screens, I wanted the banner to appear above the content and push it down the page. On larger screens I opted to affix it to the top of the viewport because it would not obstruct reading to nearly the same degree as it would on a small screen. Accomplishing this involved very little code:

#cookie-banner {

background: #000;

color: #fff;

font-size: .875rem;

text-align: center;

}

@media (min-width: 60em) {

#cookie-banner {

position: fixed;

top: 0;

left: 0;

right: 0;

z-index: 1000;

}

}Using the browser’s default styles, the cookie banner already displays block, so I didn’t really need to do much apart from set some basic text styles and colors. For the large screen (the “full-screen” version comes in at 60 ems), I affix it to the top of the screen using position: fixed, with a top offset of 0. Setting its left and right offsets to 0 ensures it will always take up the full width of the viewport. I also set the z-index quite high so it sits on top of everything else in the stack.

Here’s the result:

Once the basic design was there, I took another pass to spice it up a bit. I decided to have the banner animate in and out using CSS. First things first: I created two animations. Initially, I tried to run a single animation in two directions for each state (opening and closing) but ran into problems triggering the reversal — you might be better at CSS animations than I am, so feel free to give it a shot. In the end, I also decided to tweak the two animations to be slightly different, so I’m fine with having two of them:

@keyframes cookie-banner {

0% {

max-height: 0;

}

100% {

max-height: 20em;

}

}

@keyframes cookie-banner-reverse {

0% {

max-height: 20em;

}

100% {

max-height: 0;

display: none;

}

}Not knowing how tall the banner would be (this is responsive design, after all), I needed it to animate to and from a height of auto. Thankfully, Nikita Vasilyev published a fantastic overview of how to transition values to and from auto a few years back. In short, animate max-height instead. The only thing to keep in mind is that the size of the non-zero max-height value you are transitioning to and from needs to be larger than your max, and it will also directly affect the speed of the animation. I found 20 ems to be more than adequate for this use case, but your project may require a different value.

It’s also worth noting that I used display: none at the conclusion of my cookie-banner-reverse animation (the closing one) to ensure the banner becomes unreachable to users of assistive technology such as screen readers. It’s probably unnecessary, but I did it as a failsafe just in case something happens and JavaScript doesn’t remove the banner from the DOM.

Wiring it up required only a few minor tweaks to the CSS:

#cookie-banner {

…

box-sizing: border-box;

overflow: hidden;

animation: cookie-banner 1s 1s linear forwards;

}

#cookie-banner.closing {

animation: cookie-banner-reverse .5s linear forwards;

}This assigned the two animations to the two different banner states: The opening and resting state, cookie-banner, runs for one second after a one-second delay; the closing state, cookie-banner-reverse, runs for only half a second with no delay. I am using a class of closing, set via the JavaScript I showed earlier, to trigger the state change. Just for completeness, I’ll note that this code also stabilizes the dimensions of the banner with box-sizing: border-box and keeps the contents from spilling out of the banner using overflow: hidden.

One last bit of CSS tweaking and we’re done. On small screens, I’m leaving a margin between the cookie notice (#cookie-banner) and the page header (.banner). I want that to go away when the banner collapses, even if the cookie notice is not removed from the DOM. I can accomplish that with an adjacent-sibling selector:

#cookie-banner + .banner {

transition: margin-top .5s;

}

#cookie-banner.closing + .banner {

margin-top: 0;

}It’s worth noting that I am setting the top margin on every element but the first one, using Heydon Pickering’s clever “lobotomized owl” selector. So, the transition of margin-top on .banner will be from a specific value (in my case, 1.375 rem) to 0. With this code in place, the top margin will collapse over the same duration as the one used for the closing animation of the cookie banner and will be triggered by the very same class addition.

Simple, Robust, Resilient

What I like about this approach is that it is fairly simple. It took only about an hour or two to research and implement, and it checks all of the compliance boxes with respect to the EU law. It has minimal dependencies, offers several fallback options, cleans up after itself and is a relatively back-end-agnostic pattern.

When tasked with adding features we may not like — and, yes, I’d count a persistent nagging banner as one of those features — it’s often tempting to throw some code at it to get it done and over with. JavaScript is often a handy tool to accomplish that, especially because the logic can often be self-contained in an external script, configured and forgotten. But there’s a risk in that approach: JavaScript is never guaranteed. If the feature is “nice to have,” you might be able to get away with it, but it’s probably not a good idea to play fast and loose with a legal mandate like this. Taking a few minutes to step back and explore how the feature can be implemented with minimal effort on all fronts will pay dividends down the road. Believe me.

Further Reading

- How Marketing Changed OOP In JavaScript

- An Introduction To Full Stack Composability

- New CSS Viewport Units Do Not Solve The Classic Scrollbar Problem

- WordPress Playground: From 5-Minute Install To Instant Spin-Up

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers

Register for free to attend Axe-con

Register for free to attend Axe-con