How To Prototype IoT Experiences: Building The Hardware (Part 1)

The world is constantly evolving with frameworks, such as the Internet of Things (IoT) and virtual reality (VR). These and many others are opening opportunities to rethink how we approach prototyping: They introduce avenues to marry the digital software with the tangible aspect of the overall user engagement.

This two-article series will introduce readers of different backgrounds to prototyping IoT experiences with minimum code knowledge, starting with affordable proof of concept platforms, before moving to costly commercial offerings.

- “Part 1: Building the Hardware” will identify the problem, the criteria for selecting hardware and, finally, how to put the different pieces of equipment together.

- In “Part 2: Configuring the Software,” we will continue the discussion by writing the code to control the hardware and connect the hardware to the Internet, and we will design custom interfaces to display the collected data.

We will do this by going over a personal experience I had as a user experience designer while learning the basics of an IoT platform named “Adafruit IO”. This will be a nice introductory case study.

The following are some assumptions about you:

- You can read code and may have even written some on your own (we’re not going to learn coding basics here).

- You have some understanding of circuitry and electronics. For more on this, see the “Resources” section.

- You are curious and like to explore and tinker.

Disclaimer: I am not an electronics engineer or a developer. Please always be careful when exploring electricity and hardware. This tutorial is meant to inspire you to do additional research before finding what works for your circumstances!

If this sounds appealing, let’s dive into part 1!

The Problem

Some Quick Definitions

IoT talk is sometimes unnecessary complex. To reduce the jargon, I will use some reader-friendly terms, as defined below.

- board. You can think of the board as a mini-computer that holds the software in code form (often called firmware) that is responsible for determining how different sensors and the board itself behave in response to inputs from and outputs to their environment. A more technical term is microcontroller unit (MCU).

- cloud. There are a ton of definitions and as many philosophical debates regarding this term. For the purpose of this series, let’s define it as any remote servers, plus inbound and outbound connections to and from them.

- ecosystem. This is a collection of hardware and software that create a unique overall experience for the end user.

- rig. The board, power supply unit and any attached sensors form a cohesive hardware unit.

Needs And Early Explorations

On a cold winter day, I read an article on smart homes being the future, which immediately inspired me to turn my home into a smart one. This translated into several commercial product purchases, including devices from the Nest family, which just whet my appetite.

Controlling my air conditioning and furnace and detecting possible carbon monoxide emissions were not enough! I wanted to go further by having monitoring capabilities over my home security. This includes:

- tracking doors opening and closing,

- verifying the occurrence of a fire or flood,

- looking at temperature and humidity,

- capturing movement in my garage.

Getting to the point of picking Adafruit IO as the solution was not a simple journey. Before deciding on that platform and the HUZZAH ESP8266 board, I tried several other solutions, with varying success:

- Generic ESP8266 Board (hobbyist) I gave this a go before even having selected the cloud platform for it. My experience showed me that programming the board requires additional setup, and pushing code to it is often unreliable. For the rigs that I got up and running, I noticed the Wi-Fi connection dropping completely after only a few days.

- Samsung SmartThings (commercial) This is a beautifully designed package of sensors and central wireless hub. It is part of an ecosystem that comes with a handy mobile app and support for third-party products. I spent considerable time trying to get the sensor-to-hub communication to work, but unfortunately, even with the help of the support team, it did not work. I attributed this to my home being a black hole for all things wireless.

- Particle.io (hobbyist and commercial) This ecosystem offers dedicated development tools, various IoT-based boards and robust integration with libraries. I gave it a try and was impressed with the performance and flexibility for the end user. I hit roadblocks when integrating Blynk, a platform for controlling devices via drag-and-drop interfaces. Though I am putting this approach on hold, I look forward to exploring the Particle-Blynk combination again soon.

Criteria

My vision was to have multiple sensors that could be viewed and controlled from a computer or mobile device independently at any time. To accomplish this, I needed both a Wi-Fi-enabled hardware board and a software platform that could talk to it and any attached sensors.

I decided to be more strategic in my choices, so I came up with a list of criteria, in order of priority:

- low cost For scalability, I wanted to keep the rig (i.e. board, sensors and power supply) in the $25 to $30 range — 50% less costly than commercial offerings.

- small board I wanted a small size for easy mounting and to have enough space to fit multiple sensors in a custom enclosure.

- support community In case of problems, access to learning resources and a community are key.

- wired power In tests, a 9-volt battery lasted only a day. Solar was out of the question due to poor sun coverage of the home. Thus, the board had to be able to be wired to an outlet.

- low learning curve Though I have some development experience and hardware hacking knowledge, I didn’t want this to be an arduous project.

After exploring the three approaches mentioned further above, I ruled out the following additional equipment, based on the five criteria. Keep in mind that I am giving you the high-level details — a whole article could be written on selecting a board!

| Board | What it is | Why I ruled it out |

|---|---|---|

| Arduino Yun | Offers both wired and wireless Internet connectivity, expandable RAM and onboard memory. The board has a Linux-based distribution, making it a powerful networked computer. | The price of the controller ($69) and the bulky size proved to be too limiting. Also, I didn’t need something so powerful. I ended up buying one to test out for a garden watering project. |

| Raspberry Pi 3 Model B | In addition to offering wired and wireless connectivity, it has HDMI and audio ports, Bluetooth integration and support for use of a custom-sized SD card with different operating systems. | While I could load a Linux-based operating system and use the Python language to accomplish anything, that’s not what I needed. I ended up using this platform for other projects. The $40 price tag and the bulky size were also limiting factors. |

| Raspberry Pi Zero | This $5 board packs a big punch. The powerful CPU and large RAM made it a strong contender, as did the small size and large number of GPIO pins. | Two things nixed this board. It doesn’t have on-board Wi-Fi, and so requires additional equipment. And because it is very popular, finding this board is hard. In the US, it is sold only at Micro Center, which limits it to one per home per month. (Note: At the time of writing v1.3 of the board with on board Wi-Fi and Bluetooth was not yet available.) |

Note: For more information on choosing a board for your hardware prototyping project, you can consult the excellent “Makers’ Guide to Boards.”

Further researching led me to Adafruit’s HUZZAH ESP8266 board, which is but one variation of the ESP8266 chipset; there are others, such as the NodeMCU LUA. Each has unique capabilities, so choose wisely. Here is why I selected the HUZZAH:

- the price ($10, not counting shipping);

- 12+ digital input and output pins and 1 analog pin;

- an on-board reset button

- voltage shifting from 3.3 and 5 volts (but it’s primarily a 3.3-volt board)

- a dedicated IoT service (Adafruit IO) with UI building blocks.

Getting Started

Deciding to start small, I wanted to build a sensor that tracks whether a door is open. The rest of this first article will focus on the hardware for this use case, but much of the wiring will scale to other types of sensors.

Tools

- FTDI cable ($8 – $20 on average) It’s best to get one that supports 3.3 and 5 volts, in case you want to explore rigs using the original ESP8266 ESP-01 board in the future. It must offer TX and RX LEDs for easier troubleshooting while pushing code to the board. This is used to push the code from the programming computer to the board.

- Putty ($5 – $7 on average) This is used to mount the rig without damaging the wall. Various LEGO pieces can be used to keep the sensor in place without moving.

- Ordinary soldering iron ($20 on average) This helps to attach the headers (pin legs) to the board.

The following I am assuming you having just laying around: a computer, a solder wire and a solder iron cleaner.

Hardware Components

- HUZZAH ESP8266 board ($10 on average) This is the brain that drives the hardware.

- 400-row mini-breadboard ($2 – $4 on average) This is used to plug in various electronics components.

- 9-volt 1-amp adapter ($4 – $7 on average) This powers the hardware setup. It should have enough current to power the entire rig.

- 3.3- to 5-volt regulating power breadboard supply ($3 – $6 on average) This ensures that the board has the correct 3.3-volt power.

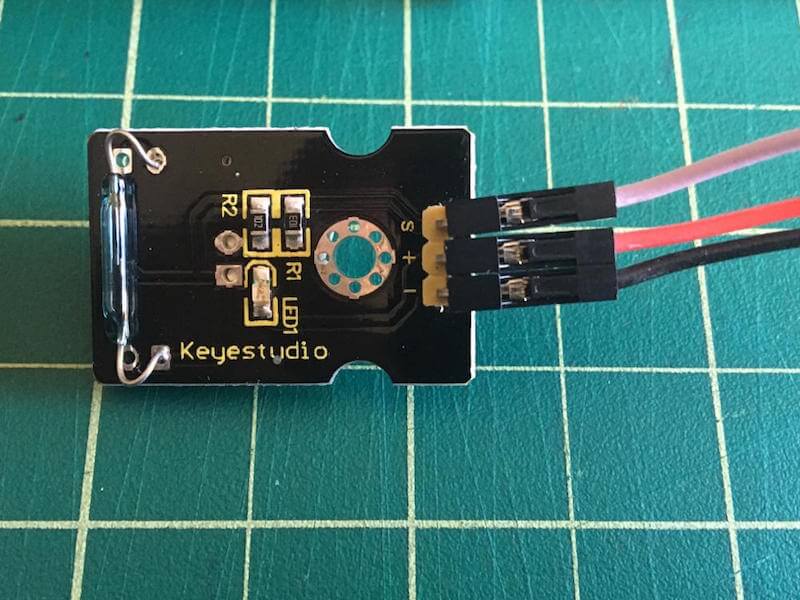

- Keyes reed switch sensor ($5 on average) This magnetic sensor helps to determine whether a door is open.

- Male-to-male and male-to-female cables ($2 – $4 on average) This connects the different hardware parts to the board and to the power.

- Small magnet ($1 on average) You can use this to trigger a door opened and closed event.

- Enclosure container ($1 – $3 on average) This is purely optional, but it brings some aesthetics to the build.

Total: $30 to $40 on average (using US parts)

Connecting The Hardware

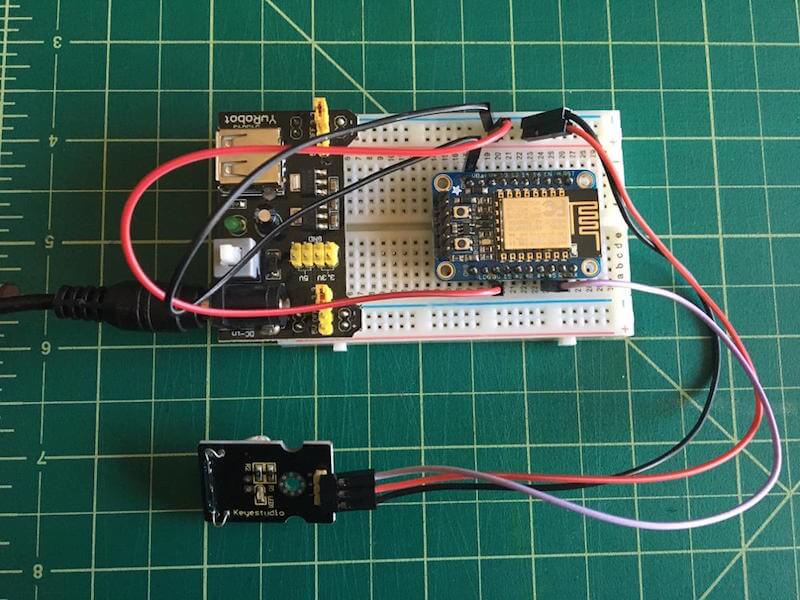

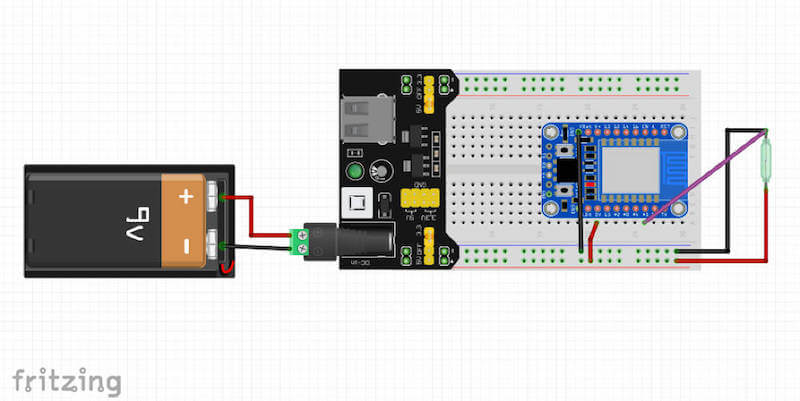

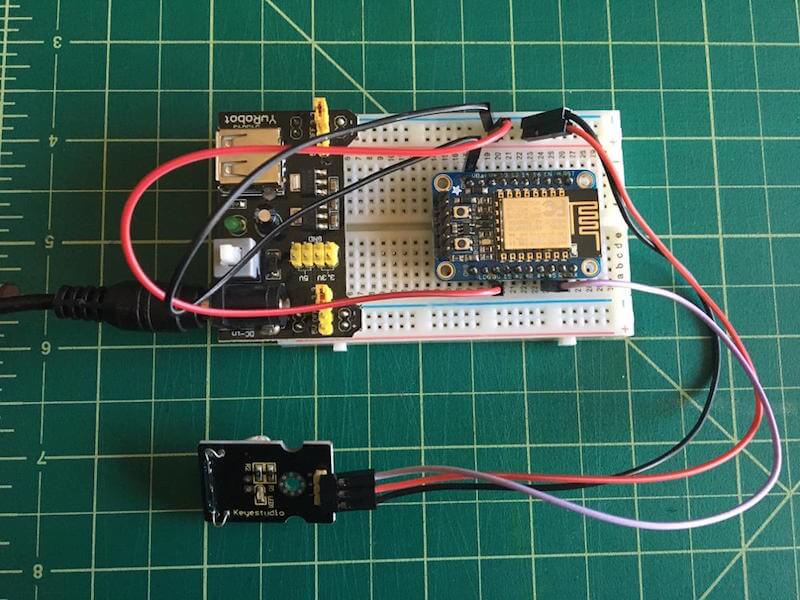

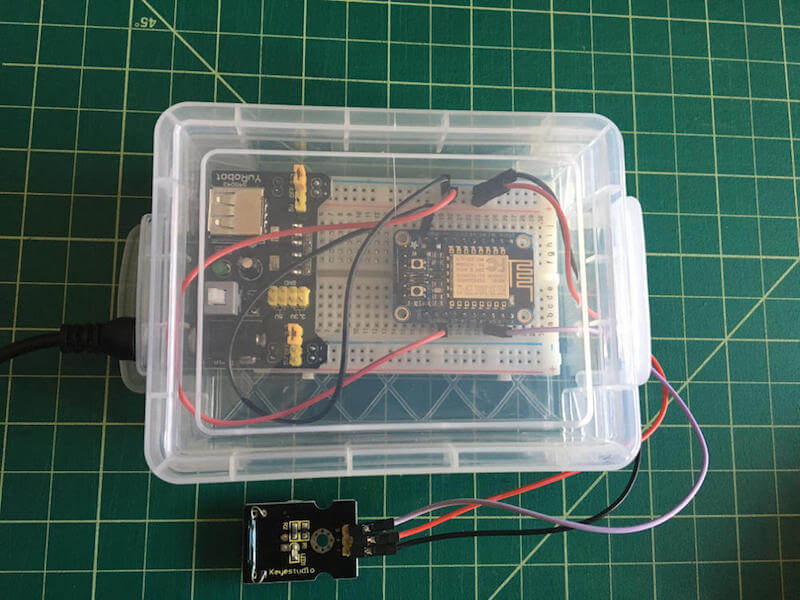

Before getting to the details of how to put the rig together, let’s talk about what the goal is. By the end of this first article, you should have something similar to what you see below. With this setup, you will have a mini-computer (the board) capable of collecting sensor data from your environment and communicating it to the cloud (Adafruit IO) over Wi-Fi.

Putting The Board Together

The first step is to assemble the HUZZAH board by soldering on its pin headers, including both the board leg headers and the FTDI header. Adafruit has a step-by-step tutorial on this.

When you are soldering the first leg header, ensure that the board is not tilting one way, which would result in the pins being soldered at an angle. A trick I used is to put a bit of putty under the board to even it out as it is being plugged into the breadboard.

Once you have soldered all of the headers, insert the board in the breadboard with the antenna (the wavy gold line) facing outwards.

Adding The Breadboard Power Supply

Insert the supply at the opposite end of the breadboard, with the top and bottom legs fitting in the + and - breadboard rails. This is how power will be passed to the breadboard.

Next, set the yellow jumpers for both rails to 3.3 volts, which is the voltage used by the HUZZAH board.

Note: Depending on your breadboard, the - and + might not match the alignment of the power supply jumpers. That’s fine as long as you remember that the power supply dictates which breadboard rail carries which electrical signal!

Wiring For Power And Connecting The Sensor

Connect the HUZZAH board to the power:

- Connect the 3V to the + rail (the power).

- Connect the GND to the – rail (the ground).

Connecting the sensor is very easy:

- Connect the + to the + rail on the breadboard (the power).

- Connect the – to the – rail on the breadboard (the ground).

- Connect the S to the #5 on the board (digital input pin).

If you are curious to learn how reed switches operate, Chris Woodford has more information on the subject.

As a last step, plug the 9-volt adapter into a power outlet, then into the breadboard power supply. Push the white button. If everything is correctly wired, you should see several lights flicker on, including for the power supply (the green one), the board power (red), the Wi-Fi (blue) and the sensor (red if the magnet is touching the sensor).

Mounting The Rig

At this point, you can start writing the code for the rig, but I find this is a good opportunity to test the mounting of the container box. This is not a permanent mounting, but a trial run to gauge the rig’s overall dimensions and the best fit. Before doing that, you need to take some steps first.

Step 1: Using your soldering iron, melt one hole in the left side of the container for the power adapter plug, and three smaller ones on the right for the individual sensor wires.

Warning: Make sure to do this in a well-ventilated area, so that you don’t breathe in fumes. After that, clean your soldering iron’s tip with a nonabrasive sponge.

Step 2: Put the entire rig in the container, and pass the cables through the holes.

Step 3: Close the container, and mount it on the wall with the putty. Tapes of various types won’t work well. Alternatively, you could punch holes in the bottom of the container to mount with screws, but make sure they are insulated with electrical tape to avoid short-circuiting any electronics.

I have also tried using hot glue. I think it is messy, but it is not all that more expensive, and you can pick one up on the cheap if you prefer that method.

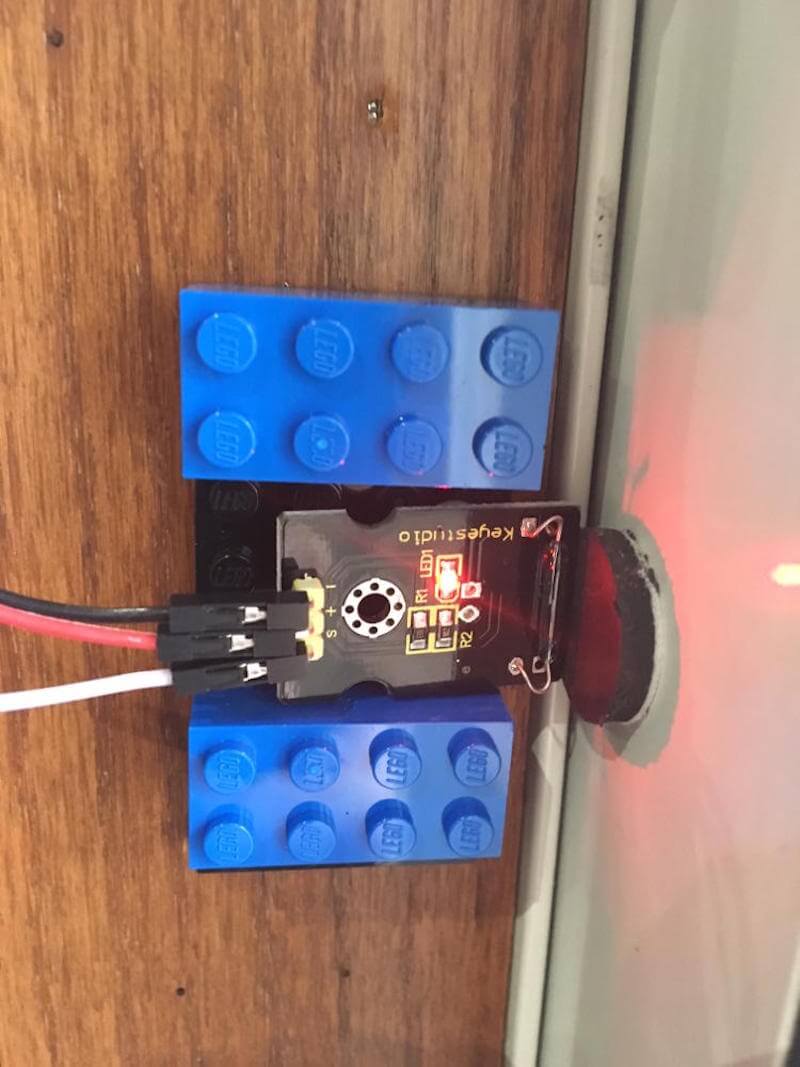

Step 4: Use a combination of LEGO pieces and putty to mount the sensor and the accompanying magnet to the door.

Now that the rig is all wired up, you can connect to it with the FTDI cable and start adding the code that will make the sensor work.

Lessons Learned And Troubleshooting

Equipment

- Using a 5-volt 1-amp power adapter (rather than 9 volts and 1 amp) won’t cut it. In my tests, the rig never powered on this way. I attribute this to the voltage conversion in the breadboard’s power supply.

- In trying different hall sensors, I was getting readings all over the board. See if they work for you, but my preference remains a reed switch because of its large surface area for interacting with the magnet.

Mounting

- Most 9-volt 1-amp power supplies have short cables. An extension cord is recommended!

- If you don’t want to damage the mounting surface, putty is your best bet. Given the weight of the rig, tape and other materials won’t work as well.

- Be careful not to place the reed switch too close to the magnet, or you’ll risk breaking the glass tube when opening and closing the door.

Conclusion

In this first article of our two-part series, we’ve identified the problem (home security), assessed the merit of an IoT setup, and discussed the rationale involved in selecting a particular board. This was followed by a step-by-step guide on how to put together all of the hardware components into a working rig.

In doing so, we’ve learned the basics of electronics. In the second (and final) article in this series, we will add code to the rig we’ve built here, so that we can start interacting with the environment. Then, we will build custom user interfaces to view the data from anywhere, while discussing at a high level the security implications of the software configuration.

Stay tuned!

Resources

Basics Of Electronics

- Collin’s Lab (John Cunningham’s YouTube tutorials)

- Make (online magazine)

- Make: Electronics, Charles Platt, O’Reilly and Make: Books

Other Hardware Platforms

Parts And Tools

Further Reading

- Choosing The Right Prototyping Tool

- Prototype And Code: Creating A Custom Pull-To-Refresh Gesture Animation

- Prototyping iOS And Android Apps With Sketch (With A Freebie!)

- iOS Prototyping With TAP And Adobe Fireworks

Register Free Now

Register Free Now

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers