Digging Into The Display Property: Box Generation

display property in CSS, this time Rachel Andrew takes a look at the values which control box generation, for those times when you don’t want to generate a box at all.This is the second in a short series of articles about the display property in CSS. You can read the initial article in the series at “The Two Values Of Display”. The display specification is a very useful spec to understand as it underpins all of the different layout methods we have.

While many of the values of display have their own specification, many terms and ideas are detailed in display. This means that understanding this specification helps you to understand the specifications which essentially detail the values of display. In this article, I am going to have a look at the box generation values of display — none and contents.

Everything Is A Box

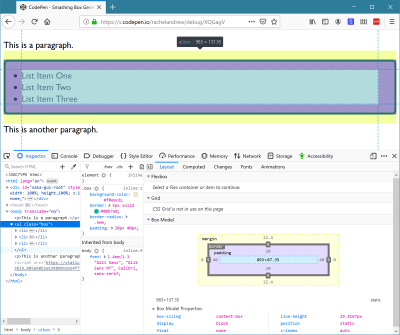

In CSS everything generates boxes. A webpage is essentially a set of block and inline boxes, something you get to understand very well if you open up DevTools in your favorite browser and start selecting elements on the page. You can see the boxes that make up the layout, and how their margins, padding and borders are applied.

ul element using Firefox DevTools so I can inspect the different parts of the box. (Large preview)Controlling Box Generation

The none and contents values of display deal with whether boxes should appear at all. If you have elements in your markup and don’t want them to generate a box in CSS then you need to somehow suppress generation of the box. There are two possible things you might want to do. Which are:

- Prevent generation of a box and all of its children.

- Prevent generation of a box but still display the children.

We can take a look at each of these scenarios in turn.

display: none

The none value of display is how we prevent the generation of a box and all the children of that box. It acts as if the element was not there at all. Therefore, it is useful in situations where you intend to completely hide that content, perhaps because it will be revealed later after activating a link.

If I have an example with a paragraph, an unordered list, and another paragraph you can see that the items are displaying in normal flow. The ul has a background and border applied, plus some padding.

See the Pen Box Generation example by Rachel Andrew.

If I add display: none to the ul it disappears from the visual display, taking with it the children of the ul plus the background and border.

See the Pen Box Generation example display: none by Rachel Andrew.

If you use display: none it hides the content from all users of the website. This includes screen reader users. Therefore, you should only use this if your intention is that the box and everything inside it is completely hidden to everyone.

There are situations where you might want to add additional information for users of assistive technology like screen readers but hide it for other users; in such cases, you need to use a different technique. Some excellent suggestions are made by Scott O ’Hara in his article “Inclusively Hidden”.

Using display: none is therefore pretty straightforward. Use it in a situation where you want a box and contents to vanish from the display, from the box tree, and from the accessibility tree (as if it were never there in the first place).

display: contents

For the second scenario, we need to look at a much newer value of display. The value display: contents will remove the box it is applied to from the box tree in the same way that display: none does, but leave the children in place. This causes some useful behavior in terms of things we can then do in our layouts. Let’s look at a simple example and then explore further.

I am using the same example as before, but this time I have used display: contents on the ul. The list items are now visible, however, they have no background and borders and are acting as if you have added li elements to the page without any enclosing ul.

See the Pen Box Generation example display: contents by Rachel Andrew.

The reason that removing a box and keeping the children is useful is due to the way that other values of display behave. When we change the value of display we do so on a box and the direct children of that box, as I described in the last article. If I add display: flex to the CSS rules for an element, that element becomes a block-level box, and the direct children become flex items. The children of those flex items return to normal flow (they are not part of the flex layout).

You can see this behavior in the next example. Here I have a containing element set to display flex, it has four direct children, three div elements and a ul. The ul has two list items. The direct children all participate in the flex layout and lay out as flex items. The list items are not direct children and so display as list items inside the box of the ul.

See the Pen Box Generation flexbox and display: contents 1 by Rachel Andrew.

If we take this example and add display: contents to the ul, the box is removed from the visual display and now the children participate in the flex layout. You can see that they do not become direct children. They are not selected by the direct child universal selector (.wrapper > *) in the way that the div and ul elements are, and they maintain the background given to them. All that has happened is that the box of the containing ul has been removed, everything else carries on as normal.

See the Pen Box Generation flexbox and display: contents 2 by Rachel Andrew.

This has potentially very useful implications if we consider elements in HTML which are important for accessibility and semantic data, but which generate an additional box that may prevent us from laying the content out with flex or grid layout.

This Is Not A CSS “Reset”

You may have noticed how one side effect of using display: contents is that the margin and padding on the element are removed. This is because they are related to the box, part of the CSS Box Model. This might lead to you think that display: contents is a good way to quickly rid yourself of the padding and margin on an element.

This is a use that Adrian Roselli has spotted in the wild; he was concerned enough to write a detailed post explaining the problems of doing so — “display: contents is not a CSS reset.” Some of the issues he raises are due to an unfortunate accessibility issue in browsers currently with display: contents which we will discuss below. However, even once those issues are resolved, removing an element from the box tree simply to rid yourself of the margin and padding is somewhat extreme.

If nothing else, it would be problematic for the future maintenance of the site, a future developer might wonder why they didn’t seem to be able to apply anything to this mysterious box — missing the fact it had been removed! If you need margin and padding to be 0, do your future self a favor and set them to 0 in a time-honored way. Reserve use of display: contents for those special cases where you really do want to remove the box.

It is also worth noting the difference between display: contents and CSS Grid Layout subgrid. Where display: contents completely removes the box, background, and border from the display, making a grid item a subgrid would maintain any box styling on that item, and just pass through the track sizing so that nested items could use the same grid. Find out more in my article, “CSS Grid Level 2: Here Comes Subgrid.”

Accessibility Issues And display: contents

A serious issue currently makes display: contents not useful for the very thing it would be most useful for. The obvious cases for display: contents are those cases where additional boxes are required to add markup that makes your content more easily understood by those using screen readers or other assistive devices.

The ul element of our list in the first display: contents CodePen is a perfect example. You could get the same visual result by flattening out the markup and not using a list at all. However, if the content was semantically a list, would be best understood and read out by a screen reader as a list, it should be marked up as one.

If you then want the child elements to be part of a flex or grid layout, just as if the box of the ul was not there, you should be able to use display: contents to magic away the box and make it so — yet leave the semantics in place. The specification says that this should be the case,

“Thedisplayproperty has no effect on an element’s semantics: these are defined by the document language and are not affected by CSS. Aside from the none value, which also affects the aural/speech output and interactivity of an element and its descendants, thedisplayproperty only affects visual layout: its purpose is to allow designers freedom to change the layout behavior of an element without affecting the underlying document semantics.”

As we have already discussed, the none value does hide the element from screen readers, however, other values of display are purely there to allow us to change how things display visually. They should not touch the semantics of the document.

For this reason, it took many of us by surprise to realize that display: contents was, in fact, removing the element from the accessibility tree in the two browsers (Chrome and Firefox) that had implemented it. Therefore changing the document semantics, making it so that a screen reader did not know that a list was a list once the ul had been removed using display: contents. This is a browser bug — and a serious one at that.

Last year, Hidde de Vries wrote up this issue in his post “More Accessible Markup with display:contents” and helpfully raised issues against the various browsers in order to raise awareness and get them to work on a fix. Firefox have partially fixed the problem, although issues still exist with certain elements such as button. The issue is being actively worked on in Chrome. There is also an issue for WebKit. I’d encourage you to star these bugs if you have use cases for display: contents that would be impacted by the issues.

Until these issues are fixed, and the browser versions which exhibited the issue fall out of use, you need to be very careful when using display: contents on anything which conveys semantic information and needs to be exposed to assistive technology. As Adrian Roselli states,

“For now, please only use display: contents if you are going to test with assistive technology and can confirm the results work for users.”

There are places where you can safely use display: contents without this concern. One would be if you need to add additional markup to create fallbacks for your grid of flex layouts in older browsers. Browsers which support display: contents also support grid and flexbox, therefore you could display: contents away the redundant div elements added. In the example below, I have created a float based grid, complete with row wrappers.

I then use display: contents to remove the row wrappers to allow all of the items to become grid items and therefore be able to be part of the grid layout. This could give you an additional tool when creating fallbacks for advanced layouts in that if you do need to add extra markup, you can remove it with display: contents when doing your grid or flex layout. I don’t believe this usage should cause any issues — although if anyone has better accessibility information than me and can point out a problem, please do that in the comments.

See the Pen Removing row wrappers with display: contents by Rachel Andrew.

Wrapping Up

This article has taken a look into the box generation values of the display property. I hope you now understand the different behavior of display: none — which removes a box and all children completely, and display: contents which removes just the box itself. You also should understand the potential issues of using these methods where accessibility is concerned.

Further Reading

- The Times You Need A Custom @property Instead Of A CSS Variable

- Level Up Your CSS Skills With The :has() Selector

- Motion Controls In The Browser

- Performance Game Changer: Browser Back/Forward Cache