Growing UX Maturity: Knowledge Sharing And Mentorship (Part 2)

This series of articles presents tactics UX practitioners can use to promote the growth of UX maturity in their organizations or product teams. I covered the importance of finding and utilizing UX Champions and showing the ROI/value of UX in the first article of this series. Today, I’ll focus on two additional tactics for UX practitioners to grow their organization’s UX maturity in this article, knowledge sharing and mentorship.

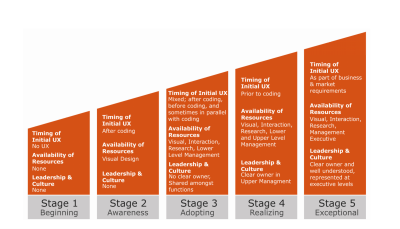

Chapman and Plewes’ framework (see image below) describes five steps or stages of organizational UX maturity that I’m referencing when I mention UX maturity stages within the tactics I present.

The table below lists the six tactics and their relationship to UX maturity. Note that the tactics don’t build on the prior tactics, you can and should implement multiple tactics simultaneously. However, some tactics, such as mentoring, might not be possible in an organization with low UX maturity that lacks the support for a mentoring program.

- Finding and utilizing UX Champions (Jump to Part 1 →)

Beginning stages: the UX champion will plant seeds and open doors for growing UX in an organization. - Demonstrating the ROI/value of UX (Jump to Part 1 →)

Beginning stages justify more investment; later stages justify continued investment. - Knowledge Sharing/Documenting what UX work has been done

Less relevant/possible in the earliest stages of maturity when there is little UX being done. Creates a foundation and then serves to maintain institutional knowledge even when individuals leave or change roles. - Mentoring

Middle and later stages of maturity. Grow individual skills in a two-way direction that also exposes more people to UX and improves the knowledge transfer of more senior UX, which should lead to a shared understanding of how UX looks and is implemented in the organization. - Education of UX staff on UX tools and specific areas of UX expertise (Jump to Part 3 →)

All stages of maturity require continued education of UX staff. - Education of non-UX staff on UX principles and processes (Jump to Part 3 →)

All stages of maturity benefit from the education of non-UX staff.

I’ll focus on two tactics in this article:

- Tactic #3

Knowledge sharing/document what’s been done and make it available across the organization; - Tactic #4

Mentorship

These two tactics are particularly applicable for an organization at stage 3 or early stage 4 of Chapman and Plewes’ UX maturity model. These tactics serve to document and build upon existing UX accomplishments, provide UX resources for current and future staff, and create and propagate the specific UX processes and values within your organization.

Tactic 3: Knowledge Sharing/Document What’s Been Done And Make It Available Across The Organization

Organizations with more mature UX have well-documented UX processes, as well as a history of what they have learned through UX research and exploration through design iteration and testing. You can’t create a mature organization without lessons learned. Mature organizations do not reinvent the wheel each time they start a product or project, in terms of how UX is integrated. Organizations with more mature UX gain efficiency through documentation of the lessons learned from past UX, and consistency in how UX is practiced/applied across products.

Each organization might have a unique culture of how information is documented and shared. Sometimes intranets and shared internal sites are highly used and easily searchable for the content you need. Sometimes, not so much. In the latter case, these repositories gather dust, and the knowledge is eventually lost in time which is replaced with something flashier or something considered more in-line with the needs of the company.

You will need to decide what might be the best way to both document and then preserve lessons learned for the needs of your organization. Here are some options:

- Manual sending/sharing

Manual sharing includes one on one and group conversation about UX research and design with other professionals both within and outside of UX roles at your organization. This can include e-mailing reports and files as attachments or links for others to access. This is the most time-consuming and least impactful in terms of the ability to have others easily find your work. You’re essentially relying on word of mouth and for others to save your work to pass along to future team members. I still suggest having these conversations as often as possible. There is a lot of value in these conversations when you have them with individuals and they see your passion for UX and creating great experiences.

- Informal meetings, one-off presentations, lunch and learns, and cross-project meetings focused on the organization’s UX work

These are events where you can talk about relevant examples of UX from projects or products within the organization. The great parnjksvt of this is making connections between the people attending these presentations, who might otherwise not interact with each other during the course of their day-to-day tasks. As with manual sharing, this is time-consuming and relies on getting the right people in the room. You can increase the impact of these events if you record them and share out the video link with others who are unable to attend live. - Catalogued research and files accessible online

This can include traditional go-to file repositories: Sharepoint sites, Onedrive, Box.com, Dropbox, and Google Drive (whatever platform works for your organization). You might also look towards licensing UX-specific platforms meant for storing and sharing UX research and product information such as Handrail, Productboard, and other collaboration tools that offer repositories. (Note: I haven’t used nor do I endorse either platform listed.)

While any of these options offer the positive side of being accessible by anyone within the organization, each has the drawback that people need to know how to access it and how to use it. Also, each needs someone to create and maintain standards like tags and naming conventions, if it will stay manageable and useful. UXPin offers a resource detailing what you can consider documenting as part of your UX documentation, and Nielsen Norman Group offers a guide for setting up a research repository.

- Systems and guides

Organizations reaching the highest levels of UX maturity have design standards and design systems in place that include content and code for facilitating UX consistency and standards across the organization. Audrey Hacq provides a thorough guide to what makes up a design system. Hacq, in citing the words of Jina Anne states that design systems consist of “Tools for designers & developers, patterns, components, guidelines” as well as “brand values, shared ways of working, mindset, shared beliefs.”

The drawback with a design system is the effort you will need to put in to create and maintain the system. You aren’t likely to have the time or ability to mandate the use of the design system if you are in an organization with little UX maturity. However, you can set your sights on reaching this level of documentation, and as UX becomes more prevalent and resources are increased, the value of creating the system will overcome the inertia that might initially exist to such a large endeavor.

You might consider a mix of the options above. For example, you should always consider including informal and one-off presenting opportunities in conjunction with something more formalized and enduring. However you decide to start documenting your UX, you need a foundation in order to grow and focus energy on other areas of UX. You don’t want to start your process from scratch each time.

If your organization is in the beginning stages of UX you might find yourself responsible for starting the repository. You might not have control over each area or product UX work is occurring, or how documentation occurs. You can attempt to work with others in order to standardize what and how things are documented. You can also use the list from UXPin to begin documenting what you can, and add to this as you get more resources or other motivated UX practitioners join your organization.

Case Study: Large Pharmaceutical Company With Low UX Maturity

We were tasked with building UX capacity and documenting the accomplishments of specific UX work over the course of eight months working across product teams with a large pharmaceutical company. We conducted stakeholder and user interviews, redesigned a number of products, and did usability testing of current and future designs. We documented our processes and accomplishments with interview protocols, sketch files, journey maps, research reports, usability testing finding and recommendation reports, and decision trees to use for the creation of future designs.

We used each of the methods listed above to share the knowledge we’d gained and document this for future staff engaging in UX work at the company.

- Manual sending/sharing

We worked directly with members of various teams to provide them an understanding of the research protocols and other outputs our team created. We also shared these files in an editable format for them to repurpose or use as templates for later projects. We used our contacts to identify people who might benefit from having the documents and included them in emails containing the files. - Informal meetings, one-off presentations, lunch and learns, and cross-project meetings

The company was very large, with staff located across the world. We were fortunate to have an effective internal Champion who was able to identify critical individuals and teams for us to present our work too. We also spent time onsite at various locations and were able to have one on one conversations with key parties who we were introduced to while we were on site. Many of these interactions were impromptu, and would not have occurred if we did not have a presence and an insider advocating for us to share our work. We presented multiple times on the various aspects of the work we were doing, and tailored the message to be effective to the audience — e.g., tactical usability testing findings were presented to product team members, while higher-level overviews and near-final designs were presented to key executive stakeholders. - Catalogued research and files accessible online

The company used a number of common platforms for archiving and storing documents. We created a UX-specific repository and tagged the content with user-friendly tags, using terminology that would be familiar to company staff across the organization. We shared the link to the page and the documents in as many forums, online, email, and in documents, as we could. - Systems and guides

We didn’t create a design system. We did create a guide for making certain UX decisions for a specific set of products the company had. Essentially, a decision tree to determine if there was a need to update an element of the design, and if so, whether we had any existing information from our research and design to help inform the new element, or if new research and testing would be required. This document was shared with the appropriate members of the product teams, as well as with managers who might be able to advocate the creation of similar guides for other products as more UX work was accomplished.

While I can’t speak to the long-term impact of our work, we left behind a foundation of UX outputs that were well documented, distributed, and accessible for reference in the future. We completed our time with the client and left them with the framework for how to continue conducting, documenting, and distributing UX work. You can use similar techniques and tailor them to the needs and culture of your organization.

Tactic 4: Mentorship

You, your organization, and your peers all stand to gain from an effective mentorship program. Mentorship, possibly more than any other kind of training or experience, has the potential to grow individuals’ skills, create cohesive teams, and shape the UX philosophy and processes of an organization. Mentorship is a key component of the growth of professionals in many other fields including health care and education.

Effective mentorship can help with growing your organization’s UX maturity in that you utilize the existing resources of your more experienced UX staff to grow the abilities of the less experienced staff, who in turn push the more experienced staff to grow and learn more about their own UX practice. This two-way process of growth can compound the benefit and lead to a larger change in the products and teams the UX staff work with. You can use mentorship to start a positive reaction that can set the direction for UX growth for a long-term period of time. You need to put thought into a mentorship program if you want to maximize the benefit. Since mentorship is an inherently personal relationship between the mentee and the mentor, the connection to growing UX maturity needs to be made explicit. You might also expand the influence and understanding of UX if you choose to include team members from outside of typical UX roles in your mentorship program.

You need to consider the following when designing your mentorship program:

- What is the goal

What are you trying to accomplish and what are the outcomes of your mentorship program? You should include thinking about how this program will increase UX maturity at the organizational level, and how the program will benefit participants, both as mentees and mentors. - Formal or informal

Will your program be formal with guidelines for mentors and mentees to adhere to, or will it be more informal and unstructured, with loosely defined outcomes? The table below compares some key factors differentiating formal and informal mentorship programs:

| Formal | Informal | |

|---|---|---|

| Participant Pool | Predefined roles and positions are able to or required to participate. | Individuals expressing interest are able to participate. |

| Timeline | Set timeline with milestones identified and a predefined end date. | Less structured, milestones are flexible, mentor/mentee determine end date. |

| Goals | Program managers set generic goals, mentor/mentee refine goals using existing structure. Most goals have a relationship to the growth/benefit of the organization and the individuals. | Mentor/Mentee customize goals to the needs of the individuals involved. Goals might not tie directly to the organization's needs. Mentor/Mentee revisit goals and update them to reflect the reality of how the mentee has progressed and other factors impacting the mentee. |

| Assignment | Mentors and mentees are matched through a formalized process. For example, completing a questionnaire that sees who is most aligned, matching based on role/job title, or team/product based. | Mentors and mentees have the opportunity to determine who they match with. For example, prior interactions suggest a potential for positive relationship, offering mentees a brief intro call with a number of potential mentors before deciding who they might want to match with. |

| Activities | Predefined relationship building and education opportunities, for example attending networking events, conferences, review sessions, and trainings. | Participants choose which activities and the frequency. For example, a weekly coffee chat with a monthly review meeting and informal conversations as needed. |

| Outcomes/Assessment | Outcomes and assessment are based on a template and reflect the desired outcomes of the organization. Assessment is formalized and used to determine effectiveness of the program as part of a final evaluation. | Outcomes and assessment are reflective of mentee’s needs and goals that have evolved over the course of the program. Assessment might be informal discussion and reflection. |

Whether you choose to have a formal or informal mentorship program, you can look at the line between the two as blurry. You should borrow from either side. For example, why wouldn’t you encourage coffee/tea/water walks and informal conversations as a way to build closer relationships in a formal program? And if an effective assessment exists for your organization to measure the effectiveness of your informal mentorship program, why wouldn’t you use it?

You should also give deep thought to who participates in your programs. As mentorship benefits both mentors and mentees, you can use this as an opportunity to inspire and educate more seasoned staff, along with an opportunity to grow newer employees. Reverse mentoring is a potentially powerful idea to explore when thinking about maximizing the benefit of a mentoring program to growing UX maturity. This type of mentoring involves pairing more senior-level staff as the mentees, while they gain the perspective of the more junior staff. You might find many of your senior leadership are not as familiar with UX, while newer staff have the opportunity to show them what the benefits are, turning them into advocates for UX growth in the organization.

You need to provide training and support to mentors regardless of the decision to make your program formal or informal. You cannot assume someone will make a good mentor based on how well they perform their job. We can all benefit from additional insight into research-backed ways to support mentees. An additional suggestion from research on effective mentorship programs is allowing mentors and mentees to provide input into the mentor matching process.

Case Study: Mentoring A Large Media Company Staff Member Transitioning Into A UX Role

I’ve had the privilege of serving as a mentor to someone transitioning into a UX research and strategy role at their organization. Initially, our relationship started as a formal client-consultant relationship, however, it evolved once we realized there would be an opportunity through informal mentorship-type activities for both of us to grow personally and professionally, as well as growing the role and maturity of UX at the media company.

I’ll provide the details of mentoring relationships using the factors from the chart above.

- Participant Pool

Our mentorship relationship was highly informal. We were the only people participating in the mentorship program because we chose to form the relationship after interacting with each other through professional activities and realizing our interests and goals overlapped. We didn’t initiate our relationship as a mentorship, this developed organically. - Timeline

The mentorship lasted approximately 18 months. This is notable in that the time I spent with the client was less than 12 months, we voluntarily continued our mentoring relationship and activities beyond the time I was working with the organization. In that sense, the arrangement was truly voluntary in the end, even though we initially were together as client-consultant. - Goals

Our goals shifted over time. Initially, the purpose of the mentorship was to develop the UX skills of the mentee. Our goals were broad and high level — for example, learn common UX processes, gain experience with common UX research methods. As we progressed our goals become more refined — e.g., present findings to product team X and develop a protocol for usability testing. We were able to have micro-goals that we updated frequently given our constant contact and checking in. I think there was an additional benefit in that I was working on the same products and projects as my mentee. I know this isn’t always the situation, but it allowed me to have an understanding of the day-to-day challenges and requests being made of my mentee. We were then able to turn these challenges into goals to address next. - Assignment

We self-assigned to each other. We determined to engage in mentorship on our own after spending weeks working together and realizing mentorship would further both of our goals. - Activities

We were able to frequently collaborate given the working relationship I had. I don’t think it would be realistic for mentor-mentee relationships to have as many activities as this if you aren’t able to have frequent — almost daily — interactions. Our activities informal calls, formal assignments, attending meetings together, conducting strategy sessions to roadmap goals and related activities, observation of what I did, creating and iterating on documents together, collecting and analyzing data together, co-working at each other’s spaces, co-creating reports, attending conferences together, and sharing conversation over coffee or a meal. - Outcomes/Assessment

Our assessment of the mentorship was informal and frequent. We would often discuss if we were still getting what we needed and expected out of the arrangement. Fortunately, the answer was yes. We also spent time reflecting and determining if we wanted to focus more on certain areas.

The final outcomes benefited me, the mentee, as well as the UX maturity of the organization. I grew as a mentor and as a UX practitioner. I was forced to think deeper about the things I do and why I do them throughout the course of the mentorship. My mentee was excellent at asking me to share the logic behind why we use certain methods, why we make certain recommendations, how we present findings to different stakeholders, and what supporting information I can provide to justify my process. I found it challenging and refreshing.

My mentee grew their UX knowledge and skills to the point they were able to lead the UX work on a number of projects. They accomplished the goals we had set out to accomplish, as well as many of the micro-goals we set along the way.

The organization’s UX Maturity benefited equally from the outcome of the mentorship. The mentee understood when and how to implement UX in their organization. The mentee went on to justify a budget to hire an additional UX staff that reported to them (increased resources). This allowed the mentee to have time to implement UX processes on other products that were currently lacking UX attention (improved timing of UX on a number of products). The mentee made numerous presentations to leadership and was able to get a number of the staff engaged and excited to promote the growth of UX at the organization (impact leadership and culture).

Putting These Tactics Into Practice

I’ve covered two additional tactics for UX practitioners to grow their organization’s UX Maturity. You won’t need to spend money on either of these tactics, but they do require resources of time and access to tools for storing or sharing information. You will need to decide on many of the best ways to approach information sharing or setting up a mentorship program that works for your organization.

Hopefully, I’ve demonstrated that there isn’t a large barrier to entry for either of these tactics. You can engage in knowledge sharing if you start documenting what you have learned from any UX work (these documents should already exist) and create an easy-to-find repository using the file storage system your organization uses. Or, you can create a list of relevant people to distribute UX-related material to and start sending them artifacts via email attachment. For mentorship, you don’t need to create a huge program with complex rules. I was able to engage in an informal relationship mentoring someone with whom I was already working with on a daily basis. Our key ingredient was a desire to learn from each other and common goals. Your organization might require some level of definition and oversight, but you might begin by looking at some of your teammates when it comes to exploring what the seeds of a mentorship program might look like.

You can use the tactics presented here standalone or along with the ones presented in the previous article. The third and final article focuses on the education of UX staff on UX tools and specific areas of UX expertise and the education of non-UX staff on UX principles and processes.

Further Reading

- Alternatives To Typical Technical Illustrations And Data Visualisations

- The Timeless Power Of Spreadsheets

- How To Defend Your Design Process

- Rethinking The Role Of Your UX Teams And Move Beyond Firefighting

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers

Register Free Now

Register Free Now