When CSS Isn’t Enough: JavaScript Requirements For Accessible Components

As the author of ModernCSS.dev, I’m a big proponent of CSS solutions. And, I love seeing the clever ways people use CSS for really out-of-the-box designs and interactivity! However, I’ve noticed a trend toward promoting “CSS-only” components using methods like the “checkbox hack”. Unfortunately, hacks like these leave a significant amount of users unable to use your interface.

This articles covers several common components and why CSS isn’t sufficient for covering accessibility by detailing the JavaScript requirements. These requirements are based on the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) and additional research from accessibility experts. I won’t prescribe JavaScript solutions or demo CSS, but rather examine what needs to be accounted for when creating each component. A JavaScript framework can certainly be used but is not necessary in order to add the events and features discussed.

"The requirements listed are by and large not optional — they are necessary to help ensure the accessibility of your components."

If you’re using a framework or component library, you can use this article to help evaluate if the provided components meet accessibility requirements. It’s important to know that many of the items noted are not going to be fully covered by automated accessibility testing tools like aXe, and therefore need some manual testing. Or, you can use a testing framework like Cypress to create tests for the required functionality.

Keep in mind that this article is focused on informing you of JavaScript considerations for each interface component. This is not a comprehensive resource for all the implementation details for creating fully accessible components, such as necessary aria or even markup. Resources are included for each type to assist you in learning more about the wider considerations for each component.

Determining If CSS-Only Is An Appropriate Solution

Here are a few questions to ask before you proceed with a CSS-only solution. We’ll cover some of the terms presented here in more context alongside their related components.

- Is this for your own enjoyment?

Then absolutely go all in on CSS, push the boundaries, and learn what the language can do! 🎉 - Does the feature include showing and hiding of content?

Then you need JS to at minimum toggle aria and to enable closing onEsc. For certain types of components that also change state, you may also need to communicate changes by triggering updates within an ARIA live region. - Is the natural focus order the most ideal?

If the natural order loses the relationship between a trigger and the element it triggered, or a keyboard user can’t even access the content via natural tab order, then you need JS to assist in focus management. - Does the stylized control offer the correct information about the functionality?

Users of assistive technology like screen readers receive information based on semantics and ARIA that helps them determine what a control does. And, users of speech recognition need to be able to identify the component’s label or type to work out the phrase to use to operate the controls. For example, if your component is styled like tabs but uses radio buttons to “work” like tabs, a screen reader may hear “radio button” and a speech user may try to use the word “tab” to operate them. In these cases, you’ll need JS to enable using the appropriate controls and semantics to achieve the desired functionality. - Does the effect rely on hover and/or focus?

Then you may need JS to assist in an alternative solution for providing equal access or persistent access to the content especially for touch screen users and those using desktop zoom of 200%+ or magnification software.

Quick tip: Another reference when you’re creating any kind of customized control is the Custom Control Accessible Development Checklist from the W3 “Using ARIA” guide. This mentions several points above, with a few additional design and semantic considerations.

Tooltips

Narrowing the definition of a tooltip is a bit tricky, but for this section we’re talking about small text labels that appear on mouse hover near a triggering element. They overlay other content, do not require interaction, and disappear when a user removes hover or focus.

The CSS-only solution here may seem completely fine, and can be accomplished with something like:

<button class="tooltip-trigger">I have a tooltip</button>

<span class="tooltip">Tooltip</span>

.tooltip {

display: none;

}

.tooltip-trigger:hover + .tooltip,

.tooltip-trigger:focus + .tooltip {

display: block;

}

However, this ignores quite a list of accessibility concerns and excludes many users from accessing the tooltip content.

A large group of excluded users are those using touch screens where :hover will possibly not be triggered since on touch screens, a :hover event triggers in sync with a :focus event. This means that any related action connected to the triggering element — such as a button or link — will fire alongside the tooltip being revealed. This means the user may miss the tooltip, or not have time to read its contents.

In the case that the tooltip is attached to an interactive element with no events, the tooltip may show but not be dismissible until another element gains focus, and in the meantime may block content and prevent a user from doing a task.

Additionally, users who need to use zoom or magnification software to navigate also experience quite a barrier to using tooltips. Since tooltips are revealed on hover, if these users need to change their field of view by panning the screen to read the tooltip it may cause it to disappear. Tooltips also remove control from the user as there is often nothing to tell the user a tooltip will appear ahead of time. The overlay of content may prevent them from doing a task. In some circumstances such as a tooltip tied to a form field, mobile or other on-screen keyboards can obscure the tooltip content. And, if they are not appropriately connected to the triggering element, some assistive technology users may not even know a tooltip has appeared.

Guidance for the behavior of tooltips comes from WCAG Success Criterion 1.4.13 — Content on Hover or Focus. This criterion is intended to help low vision users and those using zoom and magnification software. The guiding principles for tooltip (and other content appearing on hover and focus) include:

- Dismissible

The tooltip can be dismissed without moving hover or focus - Hoverable

The revealed tooltip content can be hovered without it disappearing - Persistent

The additional content does not disappear based on a timeout, but waits for a user to remove hover or focus or otherwise dismiss it

To fully meet these guidelines requires some JavaScript assistance, particularly to allow for dismissing the content.

- Users of assistive technology will assume that dismissal behavior is tied to the Esc key, which requires a JavaScript listener.

- According to Sarah Higley’s research described in the next section, adding a visible “close” button within the tooltip would also require JavaScript to handle its close event.

- It’s possible that JavaScript may need to augment your styling solution to ensure a user can hover over the tooltip content without it dismissing during the user moving their mouse.

Alternatives To Tooltips

Tooltips should be a last resort. Sarah Higley — an accessibility expert who has a particular passion for dissuading the use of tooltips — offers this simple test:

“Why am I adding this text to the UI? Where else could it go?”

— Sarah Higley from the presentation “Tooltips: Investigation Into Four Parts”

Based on research Sarah was involved with for her role at Microsoft, an alternative solution is a dedicated “toggletip”. Essentially, this means providing an additional element to allow a user to intentionally trigger the showing and hiding of extra content. Unlike tooltips, toggletips can retain semantics of elements within the revealed content. They also give the user back the control of toggling them, and retain discoverability and operability by more users and in particular touch screen users.

If you’ve remembered the title attribute exists, just know that it suffers all the same issues we noted from our CSS-only solution. In other words — don’t use title under the assumption it’s an acceptable tooltip solution.

For more information, check out Sarah’s presentation on YouTube as well as her extensive article on tooltips. To learn more about tooltips versus toggletips and a bit more info on why not to use title, review Heydon Pickering’s article from Inclusive Components: Tooltips and Toggletips.

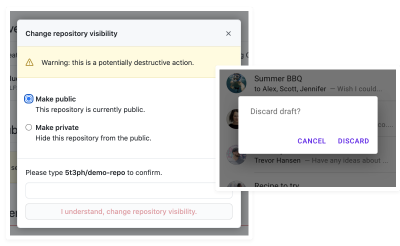

Modals

Modals — aka lightboxes or dialogs — are in-page windows that appear after a triggering action. They overlay other page content, may contain structured information including additional actions, and often have a semi-transparent backdrop to help distinguish the modal window from the rest of the page.

I have seen a few variations of a CSS-only modal (and am guilty of making one for an older version of my portfolio). They may use the “checkbox hack”, make use of the behavior of :target, or try to fashion it off of :focus (which is probably really an overlarge tooltip in disguise).

As for the HTML dialog element, be aware that it is not considered to be comprehensively accessible. So, while I absolutely encourage folks to use native HTML before custom solutions, unfortunately this one breaks that idea. You can learn more about why the HTML dialog isn’t accessible.

Unlike tooltips, modals are intended to allow structured content. This means potentially a heading, some paragraph content, and interactive elements like links, buttons or even forms. In order for the most users to access that content, they must be able to use keyboard events, particularly tabbing. For longer modal content, arrow keys should also retain the ability to scroll. And like tooltips, they should be dismissible with the Esc key — and there’s no way to enable that with CSS-only.

JavaScript is required for focus management within modals. Modals should trap focus, which means once focus is within the modal, a user should not be able to tab out of it into the page content behind it. But first, focus has to get inside of the modal, which also requires JavaScript for a fully accessible modal solution.

Here’s the sequence of modal related events that must be managed with JavaScript:

- Event listener on a button opens the modal

- Focus is placed within the modal; which element varies based on modal content (see decision tree)

- Focus is trapped within the modal until it is dismissed

- Preferably, a user is able to close a modal with the Esc key in addition to a dedicated close button or a destructive button action such as “Cancel” if acknowledgement of modal content is required

- If Esc is allowed, clicks on the modal backdrop should also dismiss the modal

- Upon dismissal, if no navigation occurred, focus is placed back on the triggering button element

Modal Focus Decision Tree

Based on the WAI-ARIA Authoring Practices Modal Dialog Example, here is a simplified decision tree for where to place focus once a modal is opened. Context will always dictate the choice here, and ideally focus is managed further than simply “the first focusable element”. In fact, sometimes non-focusable elements need to be selected.

- Primary subject of the modal is a form.

Focus first form field. - Modal content is significant in length and pushes modal actions out of view.

Focus a heading if present, or first paragraph. - Purpose of the modal is procedural (example: confirmation of action) with multiple available actions.

Focus on the “least destructive” action based on the context (example: “OK”). - Purpose of the modal is procedural with one action.

Focus on the first focusable element

Quick tip: In the case of needing to focus a non-focusable element, such as a heading or paragraph, add tabindex="-1" which allows the element to become programmatically focusable with JS but does not add it to the DOM tab order.

Refer to the WAI-ARIA modal demo for more information on other requirements for setting up ARIA and additional details on how to select which element to add focus to. The demo also includes JavaScript to exemplify how to do focus management.

For a ready-to-go solution, Kitty Giraudel has created a11y-dialog which includes the feature requirements we discussed. Adrian Roselli also has researched managing focus of modal dialogs and created a demo and compiled information on how different browser and screen reader combinations will communicate the focused element.

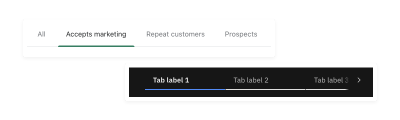

Tabs

Tabbed interfaces involve a series of triggers that display corresponding content panels one at a time. The CSS “hacks” you may find for these involve using stylized radio buttons, or :target, which both allow only revealing a single panel at a time.

Here are the tab features that require JavaScript:

- Toggling the

aria-selectedattribute to true for the current tab and false for unselected tabs - Creating a roving tabindex to distinguish tab selection from focus

- Move focus between tabs by responding to arrow key events (and optionally

HomeandEnd)

Optionally, you can make tab selection follow focus — meaning when a tab is focused its also then selected and shows its associated tab panel. The WAI-ARIA Authoring Practices offers this guide to making a choice for whether selection should follow focus.

Whether or not you choose to have selection follow focus, you will also use JavaScript to listen for arrow key events to move focus between tab elements. This is an alternative pattern to allow navigation of tab options since the use of a roving tabindex (described next) alters the natural keyboard tab focus order.

About Roving tabindex

The concept of a roving tabindex is that the value of the tabindex value is programmatically controlled to manage the focus order of elements. In regards to tabs, this means that only the selected tab is part of the focus order by way of setting tabindex="0", and unselected tabs are set to tabindex="-1" which removes them from the natural keyboard focus order.

The reason for this is so that when a tab is selected, the next tab will land a user’s focus within the associated tab panel. You may choose to make the element that is the tab panel focusable by assigning it tabindex="0", or that may not be necessary if there’s a guarantee of a focusable element within the tab panel. If your tab panel content will be more variable or complex, you may consider managing focus according to the decision tree we reviewed for modals.

Example Tab Patterns

Here are some reference patterns for creating tabs:

- Tabpanel demo from Deque University

- Tab widget tests from Scott O’Hara (tests several functional patterns)

- Tabbed Interfaces from Heydon Pickering’s Inclusive Components, which demonstrates how tabs can be a progressive enhancement of a table of contents

Carousels

Also called slideshows or sliders, carousels involve a series of rotating content panels (aka “slides”) that include control mechanisms. You will find these in many configurations with a wide range of content. They are somewhat notoriously considered a bad design pattern.

The tricky part about CSS-only carousels is that they may not offer controls, or they may use unexpected controls to manipulate the carousel movement. For example, you can again use the “checkbox hack” to cause the carousel to transition, but checkboxes impart the wrong type of information about the interaction to users of assistive tech. Additionally, if you style the checkbox labels to visually appear as forward and backward arrows, you are likely to give users of speech recognition software the wrong impression of what they should say to control the carousel.

More recently, native CSS support for scroll snap has landed. At first, this seems like the perfect CSS-only solution. But, even automated accessibility checking will flag these as un-navigable by keyboard users in case there is there no way to navigate them via interactive elements. There are other accessibility and user experience concerns with the default behavior of this feature, some of which I’ve included in my scroll snap demo on SmolCSS.

Despite the wide range in how carousels look, there are some common traits. One option is to create a carousel using tab markup since effectively it’s the same underlying interface with an altered visual presentation. Compared to tabs, carousels may offer extra controls for previous and next, and also pause if the carousel is auto-playing.

The following are JavaScript considerations depending on your carousel features:

- Using Paginated Controls

Upon selection of a numbered item, programmatically focus the associated carousel slide. This will involve setting up slide containers using roving tabindex so that you can focus the current slide, but prevent access to off-screen slides. - Using Auto-Play

Include a pause control, and also enable pausing when the slide is hovered or an interactive element within it is focused. Additionally, you can check forprefers-reduced-motionwithin JavaScript to load the slideshow in a paused state to respect user preferences. - Using Previous/Next Controls

Include a visually hidden element marked asaria-live="polite"and upon these controls being activated, populate the live region with an indication of the current position, such as “Slide 2 of 4”.

Resources For Building Accessible Carousels

- Thorough implementation details and considerations as well as a full code example from the W3C Web Accessibility tutorial on carousels

- Deque University’s example of enhancing a tab interface into a carousel

- The WAI-ARIA Authoring Practices example of an auto-rotating image carousel

- A selection of carousel resources in Smashing’s roundup of accessible components

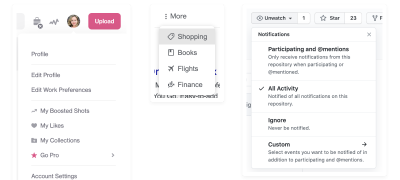

Dropdown Menus

This refers to a component where a button toggles open a list of links, typically used for navigation menus. CSS implementations that stop at showing the menu on :hover or :focus only miss some important details.

I’ll admit, I even thought that by using the newer :focus-within property we could safely implement a CSS-only solution. You’ll see that my article on CSS dropdown menus was amended to include notes and resources on the necessary JavaScript (I kept the title so that others seeking that solution will hopefully complete the JS implementation, too). Specifically, relying on only CSS means violating WCAG Success Criterion 1.4.13: Content on Hover or Focus which we learned about with tooltips.

We need to add in JavaScript for some techniques that should sound familiar at this point:

- Toggling

aria-expandedon the menu button betweentrueandfalseby listening toclickevents - Closing an open menu upon use of the Esc key, and returning focus to the menu toggle button

- Preferably, closing open menus when focus is moved outside of the menu

- Optional: Implement arrow keys as well as

HomeandEndkeys for keyboard navigation between menu toggle buttons and links within the dropdowns

Quick tip: Ensure the correct implementation of the dropdown menu by associating the menu display to the selector of .dropdown-toggle[aria-expanded="true"] + .dropdown rather than basing the menu display on the presence of an additional JS-added class like active. This removes some complexity from your JS solution, too!

This is also referred to as a “disclosure pattern” and you can find more details in the WAI-ARIA Authoring Practices’s Example Disclosure Navigation Menu.

Additional Resources On Creating Accessible Components

- Smashing’s Complete Guide to Accessible Front-End Components

- Carie Fisher’s article Good, Better, Best: Untangling The Complex World Of Accessible Patterns

- Demos and information on common design patterns and widgets available from the WAI-ARIA Authoring Practices 1.2

- Deque University’s Code Library

- Scott O’Hara’s Accessible Components

- Heydon Pickering’s Inclusive Components

Further Reading

- 35 Beautiful Vintage and Retro Photoshop Tutorials

- 60 Rare and Unusual Vintage Signs

- Vintage and Retro Typography Showcase

- Rediscovering The Joy Of Design

Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App Register Free Now

Register Free Now Register for free to attend Axe-con

Register for free to attend Axe-con