How To Build An Ethical User Research Practice At Any Organization

Ethics are an important part of human-computer interaction because they keep people at the heart of the design process. Unethical practices at companies lead to the creation of technology that we all use but often neglect the influence of those intended to serve. As seen in the discussions about privacy at Facebook and AI-powered imaging at Google among other examples, when there are no ethical considerations during the creation of technology then the interaction between humans is compromised.

A real interaction between computers and humans starts at technological conception by understanding users through a sound and ethical user research discipline.

What Are “Ethics” And Why Should I Care?

To understand why we should build an ethical user research practice at our organizations, we’ll start with the basics. What are ethics anyway?

Ethics are the moral standards by which a person (or in this context, a company or team) should govern the behavior or the conduct of an activity. Ethical user research should then be about protecting the dignity, rights, and welfare of the participants from whom we are asking so much information or data. If we aren’t proactive and prescriptive about our own standards as a research team, we could unconsciously be biased, demoralizing, exclusive, or even in breach of the law.

Here are a few examples of unethical practices:

- Not recruiting a diverse and inclusive sample.

- Not informing participants of study requirements or potential harm.

- Misplacing or not tracking participant data or identifiable information.

- Misgendering or reinforcing stereotypes in reports, personas, or prototypes.

You may be wondering why you specifically should care. Doesn’t somebody else in the organization focus on ethics? Isn’t there an ethics Internal Review Board (IRB) that is better suited for this? Unfortunately in the user experience industry, that answer is usually no.

While many companies rely on their own Ethics or HR departments to set governing moral standards, their scope typically only relates to their business’ product offerings, services to customers, internal processes, and functions. Rarely, if ever, do these departments take into account the specialty of user research.

For example, try and recall the last time your team’s processes were audited for compliance against the company’s ethical standards. For this reason, it’s really up to each of us; it’s up to each and every practitioner to set standards to which ourselves, our teams, and our company should be held accountable.

Victor Yocco, an avid author and speaker on the intersection of psychology and research, provides a compelling case to self educate, attend training and sustain close review of our practice in his thoughtful article on “Ethical Considerations In UX Research: The Need For Training And Review”:

“Researchers by training and trade have often been required to take courses and pass exams to reflect an awareness of potential ethical issues in research. We can best prepare our colleagues to avoid these situations through similar training and standards.”

— Victor Yocco

Unfortunately, many organizations may not have the resources to fund such training, nor provide the time needed to invest in it. Even if your organization did have the time and resources to provide such training, then what? How do you get started leveraging ethics in your user research practice to influence how you do your work in a way that upholds a set of guiding standards? It all starts with a Code of Ethics.

“I do not believe in the immortality of the individual, and I consider ethics to be an exclusively human concern with no superhuman authority behind it.”

— Albert Einstein

A Code Of Ethics: The Backbone Of Ethical Practice

Now that you understand why ethics matter for user research, and why it’s critical that you take it upon yourself to create them for your team, it would certainly help knowing where to start. To begin influencing your work with a set of ethical standards, you need to start by defining what your standards even are.

“

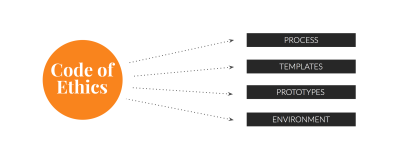

Starting with a Code versus diving headfirst into changing templates, tools, and processes that allow you to start from a reference point. A Code affords you with a checklist to ensure that with each new process, each new tool or each new study conducted follows your agreed-upon moral standards.

Once you create your own code of ethics, you might notice an improvement not only in your team’s work and performance but also in the team’s culture as well. As UX practitioners, we know empathy is an important part of the design process. Providing a deeper connection and purpose in the work we do and those who we do it with fosters a more inclusive environment, and thoughtful team members as a result.

How To Create Your Own Code Of Ethics

Creating a code of ethics takes only a few thoughtful steps, and from there you will have the backbone for influencing your work through a set of aligned standards. If you’re ready to invest in building a better, more ethical future for your team, your practice, and your organization, read on.

1. Commit To Ethics As A Practice

While it may sound silly or downright obvious, this is one of the most important and often most difficult of steps to truly accomplish. The thing is, to do things correctly aligned to any set of standards means being more thoughtful and taking the necessary steps and time to get it right.

While not monumental, ethical practice is an investment. It takes effort and time to evaluate your process, templates, tools, vendors, and ways of working in order to tweak or even overhaul them in order to align with your ethical principles or moral standards.

That said, building an ethical research practice makes good business sense, which means the time and effort is well spent when you purposely recruit diverse voices, respect their rights to information security and impartially represent them within your company’s walls.

2. Explore Existing Academic And Industry Examples

Why reinvent the wheel when we already have so many inspiring starting points? Once you’re committed to ethics, you should explore other relevant examples of research ethics in the wild. Many organizations proudly share their own code of ethics with the public, serving as a worthy starting point for your own.

It would benefit any team conducting this desk research to include both academic as well as industry examples. Academia tends to include IRBs, which I find are rarely practical for industry — it’s up to us to uphold the ethics of our practice, as previously mentioned.

Here are some great examples to get you started:

- American Psychological Association

- New York University

- World Health Organization

- Nielsen Norman Group

- Interaction Design Foundation

- ESOMAR

- IDEO.

Take a ‘researcher approach’ to reviewing these examples by keeping a log of each organization’s ethical principles or guidelines. Put them each into a long word document or spreadsheet and collate across 15-20 examples. You’ll definitely notice a few strong patterns and a lot of overlap. These overlaps and key themes will serve as a jumping-off point for developing your own principles, relevant to your team, organization, and industry.

3. Familiarize Yourself With Relevant Laws

Whether only relevant to your state, union, or industry, you’ll want to make sure you’re intimately familiar with relevant laws and regulations that force compliance around a certain level of ethical practice.

For example, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) both have strict rules surrounding how organizations may collect, store and secure consumer data. This not only applies to how companies do business but how they conduct research as well! If you live in the European Union or the state of California and are not yet familiar with these laws, I highly recommend you start reading today.

These regulations are actually quite profound as they almost codify ethics into law, requiring organizations to be compliant or otherwise face penalties such as fines or legal action. While these laws are based on ethical practice, they are still bare-bones and don’t cover the full spectrum of participant welfare or dignity, which are paramount when consumers are in your charge during the course of your research.

Some industries have their own regulations or legal practices which safeguard consumer data even more tightly than GDPR or CCPA. You may be familiar with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA), which protects sensitive patient health information from being disclosed without consent or knowledge.

Many may not be familiar with other specific protections such as Customer Network Proprietary Information (CPNI) which safeguards the type, quantity, configuration, or location of telecommunications and interconnected services you use. Being mindful and educated about your industry’s specific regulations will not only keep you out of trouble but will provide yet another input into creating your own ethical user research principles.

4. Brainstorm Your Core Principles As A Team

Now the fun part! Whether your team is distributed or co-located, you’ll want to use what you’ve learned in steps 2 and 3 in order to brainstorm what principles you want to codify into your own code of ethics. There truly is no right or wrong way to do this, however, following a typical ideation workshop framework will really help add rigor to the process.

Start by affinity mapping your industry and academic examples using sticky notes, google slides or miro/mural board. Working as a team, identify the overlaps across multiple organizations by grouping the principles you feel are similar or otherwise saying the same thing. If you feel two principles are intertwined or tightly related, however, still distinct then by all means include both in the same principle.

For example “Diversity” or “Inclusion” have distinct goals, however, they’re often grouped together as “Diversity, Equity And Inclusion.” If there is strong disagreement between one or more principles that some feel should be combined while others feel should be separate, then run a dot-voting prioritization exercise. Each team member gets a dot and is allowed to cast their vote to either group or keep separate.

Then incorporate industry, state, or special laws/regulations from your research in step 3. Start by identifying any overlaps with your existing principles. If there’s overlap, simply build onto your existing principle! If you find a piece of the law is unique or demands its own dedicated principle, then by all means codify it that way!

Lastly, take a step back and look at your ethical principles as a whole set. Ideally, you would have no more than 10, no less than 4 principles — more than 10 and they’ll be hard to keep track of; less than 4 and creating specific and relevant examples when creating your Ethical Code will be difficult.

The goal is to have specific enough principles where everyone on the team can think of 2-3 examples of exactly how to apply that principle to their everyday work, without being overly general or vague. If you feel you have too many, consider if there are any overlaps or relationships between two or more and combine them accordingly into a larger principle.

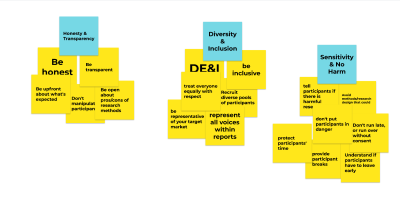

Here’re example principles after going through the exercises above:

- Sensitivity And No Harm,

- Honesty And Transparency,

- Confidentiality And Data,

- Accuracy And Impartiality,

- Diversity, Equity And Inclusion.

Once you’ve determined your high-level principles and feel good about them as a team, it’s time to make it real and draft your Code of Ethics.

5. Draft Your Code For Feedback

In order to make your Code of Ethics more easily understood, actionable and impactful, you’ll need to expand on each principle with three key components:

- A brief description

This should expound upon the principle itself and provide more detail in its definition and intention. What does honesty mean in the content of user research? When defining this principle, it’s important to note why it’s relevant in the first place and why it is a moral standard. Within this description, you’ll also want to take a moment to identify who the principle is intended for. A team that follows an honorable Code of Ethics is no doubt benefiting its research participants, but it may also apply to internal processes and stakeholder teams as well. - Bulleted agreements

Perhaps the most important piece of the Code is where it would benefit you to get specific and directly relate to the user research practice at your organization. These agreements should not only exemplify the principle itself but provide more clarity as to how the team may apply the principle in their everyday work. In a way, these become somewhat of a checklist of tactics you’ll execute every time you plan, recruit for, conduct, and report on research. - A few examples

Like that which is provided below, examples help paint a full picture of the principle in action. You want to be careful to frame your example in the context of an ethical problem, then showcase the appropriate solution which clearly ties to an agreement of the principle. Even better if you have real past experiences that you can use as examples!

Putting these components of the Code together is a great place to have a roundtable discussion about the definition of each principle as well as individual researcher’s past experiences in unique ethical situations. It becomes extraordinarily fruitful to then have an open conversation around what the team believes should be the most appropriate definition, agreements, and examples. This process not only builds collective buy-in for the Code but also deepens everyone’s understanding of each principle as well.

Here’s an example principle in action:

- Honesty And Transparency

Maintains the integrity of our individual researchers and our research work. This principle applied not only to participants but also internally when discussing study design or findings.- Inform participants of study requirements upfront;

- Inform participants where their data is going and how it will generally be used;

- Explain any purposeful manipulation at a session’s end;

- Explain the pros and cons of methodologies, and study limitations to internal stakeholders.

Example:

When designing a study with biometrics, devices with sensors need to be worn by participants. It should be communicated to participants that they will be wearing devices on or close to the skin which may cause minor irritation. The researcher should clearly explain why and where they’ll be needed in the study.

6. Implement Feedback And Finalize

When you have your first pass at your Code of Ethics and it shares collective buy-in from members of the team, it’s time to get some external validation from partner teams before considering it final.

In this step, you should schedule meetings with your points of contact from the legal and ethics departments within your organization in order to share the great work you’ve done as well as to check to make sure you’re not missing anything. It’s important to make sure you have this second pair of eyes because these groups are responsible for upholding ethics across the business and have deep knowledge of CCPA, GDPR, and other regulations which may affect your final Code.

Be warned that if you don’t already work closely with these teams, you may need to first introduce them to the type of work you do and the purpose of your team. This could mean two separate meetings; an introduction meeting may be needed to explain your team and a follow-on meeting to deep dive into your Code of Ethics.

If they’re unfamiliar with or not aware of any user research currently being done, they may already have strong concerns regarding privacy law. Remind them that’s why you’re creating this Code and why you’ve reached out to them — to ensure everyone is on the same page!

Putting It Into Practice

Now that you have a strong Code of Ethics that has internal and external team support, you’ll want to put it to work. The following are examples of where your Code of Ethics directly affects the processes, tools, and practices of your team. This is the part where the investment really comes in as each of these could take hours or even days to set the foundation for.

If you don’t proceed beyond this point and stop only when you’ve made your Code, then you run the risk of never really practicing what you’ve created. While the following isn’t quite ‘set it and forget it,’ rest assured the majority of the work is upfront in building the documentation vs. the ongoing maintenance and practice. Keep in mind these are great starting points, however, you may have other areas which could be improved using your new principles!

Screeners And Recruitment

Assuming you have an ethical principle-centered around or associated with Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DE&I), updating your screener questionnaire template and recruitment practices will help ensure every study accounts for the diversity and uniqueness of the customers for whom you serve.

In screener questionnaires, care should be taken in the administration and wording of questions relating to race, ethnicity, and gender. Because people identify in different and unique ways, these questions are asked and what responses you allow should reflect that flexibility. While there is plenty of literature out there to help you with crafting most demographics related questions, here are some ethical considerations:

- Before asking for personal information such as gender or race, provide a very brief explanation as to why you’re asking for it in the first place. Providing this context can ease the minds of those who fear their information may be used for exploitation.

- Allow ‘select all that apply’ checkbox answer options. Many may identify as mixed-race or on a spectrum of gender — providing them with multiple ways of identification more accurately represents them.

- Provide a ‘prefer not to answer’ option for those who don’t feel comfortable disclosing this information.

- For race, be exhaustive with the answer options to account for diverse classification and to avoid misrepresentation.

- For gender, include ‘non-binary’ and ‘prefer to self identify’ options to accommodate those who don’t identify within a fixed gender.

In addition to screener wording, the individuals or team responsible for study recruitment efforts should make a purposeful effort to recruit a diverse group, even for small sizes for qualitative research. When working with recruitment firms or advanced panel tools, this should be relatively straightforward.

However, committing to diversity may mean canceling a few sessions and re-recruiting if your first round of recruitment efforts result in 9⁄10 participants being middle-aged white men, for example.

Data Retention And Management

Participants often provide sensitive, personally identifiable information that they may expect will be kept private and secure. This may even be a requirement of the law, as per the aforementioned regulations (GDPR And CCPA). In order to do this, you will need to create a comprehensive Data Retention Policy for all types of information that you’re collecting from participants. While there are many GDPR And CCPA templates and resources available to help you create your own policy, the key questions that must be asked are:

- What data are you collecting?

- Are you storing it? Why/for what purpose?

- How long are you storing it for before deletion?

- How is this data being secured?

- Who, if anyone else, has access to this data?

Once you create your own Data And Retention policy, be sure to gain alignment with your own Legal team to ensure it meets the standards of local or federal requirements — especially in regards to specialized data related to CPNI or HIPPA. Then, share and train your team to uphold this policy, explaining the importance of safeguarding sensitive participant information.

An easy but effective way to hold everyone accountable to this policy is to include a ‘Data Retention Plan’ section within every Test Plan document which outlines what data is being collected during the course of the research, how it will be used, if it will be stored, and how it is being protected. For example, an in-situ contextual inquiry where COVID-19 vaccination status is being discussed, you’d want to document:

| Data | Instrument | Retention Plan | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Name And Likeness | Video/Audio Recording And Recruitment firm | Codify as ID # | Identification is not important. Participant will be anonymized. |

| Mailing Address | Recruitment Firm | Delete after data collection | Only needed for moderator’s arrival during the study. |

| Vaccination Status | Video/Audio Recording | Maintain for 6 months | Needed to create personas. Data not needed after study completion. |

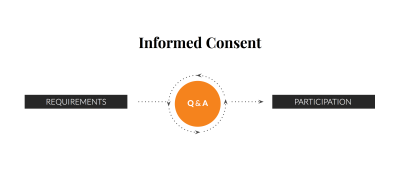

Informed Consent And NDAs

A key component of ethical user research is keeping the participant comfortable and informed at all times in order to protect their dignity and welfare. This may be done by providing them proper documentation and a forum in which to address questions or concerns that they may have prior to the study.

In addition, if a body of work is internally safeguarded or confidential, you may wish that the participants remain undisclosed. Non-disclosure Agreements must not be lengthy legal documents that are difficult to follow and require an advanced degree to read and understand.

There is more than one way to write an Informed Consent document, however, the key components are mostly the same:

- Begin by thanking the participant for their consideration of participating in the study.

- Explain the topic of the study at a high level by providing just enough detail to build an understanding of the subject matter.

- Provide a clear, bulleted list of expectations or activities the participant will be required to participate in during their session.

- Disclose any potential risk of harm, danger, or manipulation as part of the study.

- Remind them of the time commitment for the session, any follow on activities after the study, and the nature of the incentive for their involvement.

- End with a clear request to provide written consent of the above, including both their signature as well as today’s date.

It is paramount that participants are able to deny or withdraw their consent at any time, without warning or reason and without penalty — informed consent is useless if the participant is penalized or coerced into providing and maintaining their consent.

At times, our research may touch on triggering, emotional topics. Other times, there may be sudden emergencies that come up in the middle of the session. When these things happen, the participant should feel empowered to take a break or step away without fear of losing their incentive or fear of any form of retaliation.

Internal Representation: Reports, Prototypes And Personas

Ethical user research extends beyond the study and data collection, permeating into our internal artifacts that may be used for many months afterward. While there are more examples than will be covered here, the primary three areas where ethical considerations should be top of mind are in your findings reports, design prototypes, and especially in your user personas.

Findings Reports

When reporting a study’s findings, care should be taken to be as representative and impartial as you were during the design and administration of the study itself so that the audience or readers of the report have the full, accurate picture of what was learned and how.

- Provide a ‘study setup’ section of the report which outlines a brief, but robust study methodology description. Include both Pros and Cons of the study method so that you’re being transparent in its limitations and reach.

- Include a ‘participants’ section of the report which includes a bulleted list of the participant attributes. If necessary, include any footnotes around a limitation of diversity (i.e. if against all efforts you recruited 30 women of 40 total participants, this should be noted).

- When using photos, avoid participant’s faces (likeness, PII) unless you’ve been provided explicit consent to do so from the participant. This is especially important when discussing personal or sensitive topics.

- Use direct quotes, audio recordings, or photos from a range of participants to reflect and promote the diversity of your recruit. This provides the fullest picture of who you spoke with during the study.

- Don’t paraphrase direct quotes nor infer too heavily without solid context or understanding. This maintains impartiality and avoids unconscious bias.

- Avoid reporting demographic information for individual qualitative findings as it may inadvertently support institutionalized biases or stigma (i.e. 2 male Caucasians said X, 1 black woman said Y). It is best practice to segment by demographics only with quantitative samples where meaningful differences may be found through statistical analysis.

User Personas

A common framework for communicating generative user research findings is the user persona — an archetypical representation of a group of users that exhibit similar attitudes and behaviors. While incredibly powerful for making design decisions for months or even a year after the completion of research, they’re just as powerful in reinforcing gender, age, or racial stereotypes.

Care should be taken in the crafting of user personas so that they uphold their humanizing character while avoiding enforcing bias. While there are other resources for creating agnostic user persons, here are a few highlights:

- Try to avoid using human names altogether. Using human names often promote biased stereotypes given strong societal expectations around different gender roles, positions of authority, or occupational status. Instead, you may lean into pithy 2-3 word titles which better exemplify who your Personas are (i.e. ‘Cautious Comparer,’ or ‘Impulsive Spender’).

- Use gender-neutral and culturally diverse names. If you insist on using names in order to humanize the personas, use gender-neutral names to fight the unconscious gender bias. There are also many cultures and backgrounds with which your users may identify — using only names from western European etymology may incidentally erase their unique identity. Using names from diverse etymology helps fight this bias. Here are a few examples of gender-neutral, culturally diverse names: Adrian, Armani, Brett, Devon, Kai, Krishna, Maren, Noor, Nilam, Sam, Jaylin, Jordan, Yoshi.

- As with the above, leverage artistic visualizations which exemplify the Persona more accurately than a fictitious image or photo. For example, in a Persona for a car manufacturer, it is much more telling to see a weighted scale with a dollar sign on one side and the word ‘safety’ on the other side than it is to see a stock photo of a worried looking person in the front seat. Using photos or illustrations for Personas further stigmatizes race, gender, and body type. If insistent on using humanizing imagery, consider artful illustrations which are ambiguous in gender, race, and body types in order to remain inclusive.

- Do not include disability status unless this was directly part of your research or you’re creating a set of personas specifically focused on people of varying abilities or with a focus on intersectionality. Consider if this level of information or detail is important for the product you’re creating. While the goal of including this information may be with good intentions, you may be misrepresenting already marginalized communities.

- Try and avoid gender, race, sexual orientation, or other demographics that are more akin to segmentation analysis and not user personas. Personas should be representations of like-attitudes and especially behaviors which often transcend basic demographics.

As apparent by the above guidance, creating Personas tows a very fine line between creating a useful fictitious archetype and promoting bias and stigma. The latter is highly unethical and leads to false assumptions and even worse design and content strategy decisions.

Design Prototypes

Similar to the above guidance given to User Personas, the same care should be taken with users personified through prototype designs. Often we create situations or scenarios to stress test the content and interaction design of our systems by placing a fictitious character at the heart of our mock-ups.

Consider leveraging the gender-neutral and culturally diverse names above for use within your prototypes (i.e. the account name of an authenticated user). For account or profile images, leverage artistic illustrations, or a diverse range of stock photography to depict your users. When creating designs where multiple individuals will be represented, take a step back to ensure diversity in the holistic group rather than a focus on one gender, race, culture, or body type.

Bringing It All Together

Ethical user research isn’t only the right thing to do but it makes good business sense. Principles of ethical conduct guide our decision-making, keeping us out of trouble and holding us accountable to our users and society.

By influencing your practices, templates, and processes with a foundation of ethical principles you will show your team and your organization that you value the dignity and welfare of your users. Building an ethical user research practice at any organization is not inherently difficult, however, requires upfront and ongoing conscious investment in order to do so effectively.

It’s up to us to put the humans we design for at the center of our own business practices and create a true form of human-computer interaction. No one will do this work for us. Noone will hold us accountable. After all, ethics (especially in our field) are an exclusively human concern with no superhuman authority behind it.

Are you ready to make a difference?

Click here to kickstart your project for free in a matter of minutes.

Click here to kickstart your project for free in a matter of minutes.

Start with a free demo —

Start with a free demo —

Take a break with a 3D game built on Netlify!

Take a break with a 3D game built on Netlify!