Performance Signals For Customizing Website UX

In my last article, I suggested using the SaveData API to deliver a different, more performant, experience to users that expressed that desire. This hopefully leads to a greater experience for all users. In this article, I want to spend a bit more time on this, and also look at other signals we can similarly use to help us make decisions on what to load on our websites.

That’s not to say the extraneous content is pointless — enhanced design and user interfaces can have an important impact on the brand of a website, and delightful little extras can really impact your users’ relationship with your site. It’s when the cost of those “extras” starts to negatively impact your user’s experience of the site, then you should consider how essential they are, and if they can be turned off for some users.

Save Data API

Let’s have a quick recap on the Save Data API. That user preference is available in two (hopefully soon to be three!) ways:

- A

Save-Dataheader is sent on each HTTP request.

This allows dynamic backends to change the HTML returned. - The

NetworkInformation.saveDataJavaScript API.

This allows client-side JavaScript to check this and act accordingly. - The upcoming

prefers-reduced-datamedia query, which allows CSS to set different options depending on this setting.

This is available behind a flag in Chrome, but not yet on by default while it finishes standardization.

Note: At the time of writing, the Save Data API, and in fact all the options we’ll talk about in this article, are only available in Chromium-based browsers (Chrome, Edge, Opera…etc.). This is a bit of a shame, as I believe they are useful for websites. If you believe the same, then let the other browsers know you want them to support this too. All of these are on various standard tracks rather than being proprietary Chrome APIs, so they can be implemented by other browsers (Safari and Firefox) if the demand is there. However, later in this article, I’ll explain why it’s perhaps more important that they are supported in Chromium-based browsers — and Chrome in particular.

Perhaps confusingly, iOS does have a Low Data mode, though that is used by iOS itself to reduce background tasks using data, and it is not exposed to the browser to allow websites to take advantage of that (even for Chrome on iOS which is more a skin on top of Safari than the full Chrome browser).

Websites can act on the Save Data preference to give a lighter website to… well.. . save the user’s data! This is helpful for those on poor or expensive networks, so they don’t have to pay an exorbitant cost just to visit your website. This setting is used by users in poorer countries but is also used by those with a capped data plan that might be running out just before your monthly cap renewal, or those traveling where roaming charges can be a lot more expensive than at home.

And Is It Used?

Again, I talked about this that previous article, and the answer is a resounding yes! Approximately two-thirds of Indian mobile Chrome users of Smashing Magazine have this setting turned on, for example. Expanding that to look at the top-10 mobile users that support Save Data, by volume for this site, we see the following:

| Country | % Data Saver |

|---|---|

| India | 63% |

| USA | 10% |

| Philippines | 49% |

| China | 0% |

| UK | 35% |

| Nigeria | 55% |

| Russia | 55% |

| Canada | 38% |

| Germany | 35% |

| Pakistan | 51% |

Now, there are a few things to note about this. First of all, it’s, perhaps, no surprise to see high usage of this setting for what are often considered “poorer” countries — over 50% of mobile users having this setting seems common. What’s, perhaps, more surprising is the relatively high usage of a third of users using this in the likes of the UK, Germany, and France. In short, this is not a niche setting.

I’d love to know why China is so reluctant to use this if any readers know. Weirdly, they report as a range of browsers in our analytics including the Android WebView, Chrome and Safari (despite it’s not supporting this!). Perhaps, these are imitation phones or other customized builds that do not expose this setting to the end-users to enable this. If you have any other theories or information on this — I’d love to know, so please drop a message in the comments below.

However, the above table is not actually representative of total traffic, and that’s another point to note about this data. If we compare the top-10 countries that visit SmashingMagazine.com by number of users across four different segments, we see the following:

| All users | Mobile user | Mobile SaveData support | Mobile SaveData on | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | USA | USA | India | India |

| 2 | India | India | USA | Philippines |

| 3 | UK | UK | Philippines | Nigeria |

| 4 | Canada | Germany | China | UK |

| 5 | Germany | Philippines | UK | Russia |

| 6 | France | Canada | Nigeria | USA |

| 7 | Russia | China | Russia | Indonesia |

| 8 | Australia | France | Canada | Pakistan |

| 9 | Philippines | Nigeria | Germany | Brazil |

| 10 | Netherlands | Russia | Pakistan | Canada |

All users, and mobile users are not too dissimilar. Though some of the “poorer” countries like the Philippines and Nigeria are higher up in the table on mobile (desktop support of this site seems higher in Western countries).

However, looking at those with Save Data support (the same as the first table I showed), it is a completely different view; with India overtaking the USA at the top spot, and the Philippines shooting right up to number three. And finally looking at those with Save Data actually turned on, it’s an unrecognizable ordering compared to the first column.

“

I mentioned earlier that Save Data is only available in Chromium-based browsers, meaning we’re ignoring Safari users (a sizable proportion of mobile users), and Firefox. However, countless research (including the stats for our own site here, and others by the likes of Alex Russell) has shown that Android devices are the platform of choice for poorer countries with slower networks. This is hardly surprising given the cost difference between Android and iOS devices, but using the signals offered only to those devices doesn’t mean neglecting half of your user base, but instead concentrating on the users that need the most help.

Additionally, as I mentioned in the previous article, the Core Web Vitals initiative being measured only in Chrome browsers (and not other Chromium browsers like Edge or Opera) is putting a spotlight on these users, while at the same time those are the users supporting this API and others to allow you to address them.

So, while I wish there wasn’t this inequality in this world, and while I wish all browsers would support these options better, I still believe that using these options to customize the delivery better is the right thing to do, and the fact that they are only available in Chromium-based browsers at the moment is not a reason to ignore these options.

How To Act Upon Save Data

How exactly websites use this information is entirely up to the website. In the past, Chrome used to perform changes to the website by proxying requests via their servers (similar to how Opera Mini works), but doing that is usually frowned upon these days. With the increase in the use of HTTPS, site content is more secured in part to avoid any interference (Chrome never performed these automatic optimizations on HTTPS sites, though as the browser they could in theory). Chrome will soon also be sunsetting this automatic altering of content on HTTP sites. So, now it’s down to websites to do change as they see fit if they want to act upon this user signal.

Websites should still deliver the core experience of the website, but drop optional extras. For Smashing Magazine, that involved dropping some of our web fonts. For others, it might involve using smaller images or not loading videos by default. Of course, for web performance reasons you should always use the smallest images you can, but in these days of high-density mobile screens, many prefer to give high-quality images to take advantage of those beautiful screens. If a user has indicated that its preference is to save data, you could use that as a signal to drop down a level there, even if it’s not quite as nice as a picture, but still gets the message across.

Tim Vereecke gave a fantastic talk on some of the Data S(h)aver strategies he uses on his site for users with this Save Data preference, including showing fewer articles by default, loading less on infinite scroll pages when reaching the bottom of the page, removing icon fonts, or reducing the number of ads, not auto-playing videos and loads more tips and tricks, some of which he’s summarised in an accompanying article.

One important point that Tim noted is using Save Data might not always improve performance. Some of the techniques he uses like loading less or turning off prefetching of likely future pages will result in data saving, but with the downside of loading taking a bit longer if users do want to see that content. In general, however, reducing data usually results in web performance gains.

Is Save Data The Only Option?

Save Data is a great API in my opinion, and I wish more sites used it, and more browsers supported it! The fact that the user has explicitly asked sites to send less data means doing that is acting upon their wishes.

The downside of Save Data, however, is that users have to know to enable this. While many Smashing Magazine readers may be more technical and may know about this option or may be comfortable delving into the settings of their browsers, others may not. Additionally, with the aforementioned change of Chrome removing the Save Data browser option, and perhaps switching to using the OS-level option, we may see some changes in its usage (for better or worse!).

So, what can we do to try to help users who don’t have this set? Well, there are a few more signals we can use, as they also might indicate users who might struggle with the full experience of the website. However, as we are making that decision for them (unlike Save Data which is an explicit user choice), we should tread carefully with any assumptions we make. We may even want to highlight to users that they are getting a different experience, and offer them a way of opting out of this. Perhaps this is a best practice even for those using Save Data, as perhaps they’re unaware or had forgotten that they turned this setting on, and so are getting a different experience.

In a similar vein, it’s also possible to offer a Save Data-like experience to all users (even in browsers and operating systems that don’t support it) with a front end-setting and then perhaps saving this value to a cookie and acting upon that (another trick Tim mentioned in his talk).

For the remainder of this article, I’d like to look at alternatives to Save Data that you can also act upon to customize your sites. In my opinion, these should be used in addition to Save Data, to squeeze a little more on top.

Other User Preference Signals

First up we will look at preferences that, like Save Data, a user can turn on and off. A new breed of user preference CSS media queries have been launched recently, which are being standardized in the Media Queries Level 5 draft specification and many are already available in browsers. These allow web developers to change their websites, based on various user preferences:

prefers-reduced-motion

This indicates the user would prefer fewer motions, perhaps due to vestibular motion disorders. Adam Argyle has made a point of highlighting that reduced motion != no motion. Just tone it down a bit. If you were acting on the save data option, you wouldn’t hold back all data!prefers-reduced-transparency

To aid readability for those that find it difficult to distinguish content with translucent backgrounds.prefers-contrast

Similar to the above, this can be used as a request to increase the contrast between elements.forced-colors

This indicates the user agent is using a reduced color pallet, typically for accessibility reasons, such as Windows High Contrast mode.prefers-color-scheme

This can be set tolightordarkto indicate the user’s preferred color scheme.prefers-reduced-data

The CSS media query version of Save Data mentioned above.

Only some of these may have a different impact on web performance, which is my area of expertise, and the original starting point for this article with Save Data. However, they are important user preferences — particularly when considering the accessibility implications for motion sensitivity, and vision issues covered by the transparency, contrast, and even color scheme options. For more information, check out a previous Smashing Magazine article deep-diving into prefers-reduce-motion — the oldest and most well supported of these options.

Network Signals

Returning more to items to optimize web performance, the Effective Connection Type API is a property of the Network Information API and can be queried in JavaScript with the following code (again only in Chromium browsers for now):

navigator.connection.effectiveType;This then returns one of four string values (4g, 3g, 2g, or slow-2g) — the theory being that you can reduce the network needs when the connection is slower and so give a faster experience even to those on slower networks. There are a few downsides to ECT. The main one is that the definitions of the 4 types are all fixed, and based on quite old network data. The result is that nearly all users now fall into the 4g category, a few into the 3g, and very few into the 2g or slow-2g categories.

Returning to our Indian mobile users, who we saw in the last article were getting much worse experiences, 84.2% are reported as 4g, 15.1% 3g, 0.4% 2g, and 0.3% slow-2g. It’s great that technology has advanced so that this is the case, but our dependency on it has grown too, and it does mean that its use as a differentiator of “slower” users is already limited and becoming more so as time goes on. Being able to identify the 16% of slowest users is not to be sniffed at, but it’s a far cry from the 63% of users asking us to Save Data in that region!

There are other options available in the navigator.connection API, but without the simplicity of a small number of categories:

navigator.connection.rtt;

navigator.connection.downlink;Note: For privacy reasons, these return a rounded number, rather than a precise number, to avoid them being used as a fingerprinting vector. This is why we can’t have nice things. Still, for the non-tracking purposes, an imprecise number is all we need anyway.

The other downside of these APIs is that they are only available as a JavaScript API (where it’s thankfully very easy to use), or as a Client Hint HTTP Header (where it’s not as easy to use).

Client Hints HTTP Headers

The Save-Data HTTP header is a simple HTTP Header sent for all requests when a user has this turned on. This makes it nice and easy for backends to use this. However, we can’t get other information like ECT in similar HTTP headers without severely bulking up all requests for web browsing when the vast majority of websites will not use it. It also introduces privacy risks by making available more than we strictly need about our users.

Client Hints is a way to work around those limitations, by not sending any of this extra information by default, and instead of having websites “opting in” to this information when they will make use of this. They do this by letting browsers know, with the Accept CH HTTP Header, what Client Hint headers the page will make use of. For example, in the response to the initial request, we could include this HTTP Header:

accept-ch: ect, rtt, downlinkThis can also be included in a meta element in the page contents:

<meta http-equiv="Accept-CH" content="ECT, RTT, Downlink">This then means that any future requests to this website, will include those Client Hint HTTP Headers, as well as the usual HTTP Headers:

downlink: 10

ect: 4g

rtt: 50Important! If making use of Client Hints and returning different results for the same URL based on these, do remember to include the client hint headers you are altering content based upon, in your Vary header, so any caches are aware of this and won’t serve the cached page for future visits unless they also have the same client hint headers set.

You can view all the client hints available for your browser at https://browserleaks.com/client-hints (hint: use a Chromium-based browser to view this website or you won’t see much!). This website opts into all the known Client Hints to show the potential information leaked by your browser but each site should only enable the hints they will use. Client Hints are also by default only sent on requests to the original origin and not to third-party requests loaded by the page (though this can be enabled through the use of Permission Policy header).

The main downside of this two-step process, which I agree is absolutely necessary for the reasons given above, is the very first request to a website does not get these client hints and this is in all likelihood the one that would benefit most from savings based on these client hints.

The BrowserLeaks demo above actually cheats, by loading that data in an iframe rather than in the main document, to get around this. I wouldn’t recommend that option for most sites meaning you are either left with using the JavaScript APIs instead, only optimizing for non-first page visits, or using the Client Hint information independent requests (Media, CSS or JavaScript files). That’s not to say using them independent requests is not powerful, and is particularly useful for image CDNs, but the fastest website is one that can start rendering all the critical content from the first response.

Device Capability Signals

Moving on from User and Network signals, we have the final category of device signals. These APIs explain the capabilities of the device, rather than the connection, including:

| API | JavaScript API | Client Hint | Example Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of processors | navigator.hardwareConcurrency | N/A | 4 |

| Device Pixel Ratio | devicePixelRatio | Sec-CH-DPR, DPR | 3 |

| Device Memory | navigator.deviceMemory | Sec-CH-Device-Memory, Device-Memory | 8 |

I’m not entirely convinced the first is that useful as nearly every device has multiple processors now, but it’s usually the power of those cores that are more important than the number, however, the next two have a lot of potential for optimizing for.

DPR has long been used to serve responsive images - usually through srcset or media queries than above APIs, but the JavaScript and Client Hint header options have been utilized less by websites (though many image CDNs support sending different images based on Client Hints). Utilizing them more could lead to valuable optimizations for sites — beyond the static media use cases we’ve typically seen up until now.

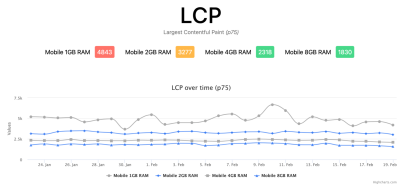

The one that I think could really be used as a performance indicator is Device Memory. Unlike the number of processors, or DPR, the amount of RAM a device has is often a great indicator as to whether it’s a “high end” device, or a cheaper, more limited device. I was encouraged to investigate how this correlated to Core Web Vitals by Gilberto Cocchi after my last article and the results are very interesting as shown in the graphs below. These were created with a customized version of the Web Vitals Report, altered to allow reporting on 4 dimensions.

Largest Contentful Paint (LCP) showed a clear correlation between poor LCP and RAM, with the 1 GB and 2 GB RAM p75 scores being red and amber, but even though the higher RAM both had green scores, there was still a clear and noticeable difference, particularly shown on the graph.

Whether this is directly caused by the lack of RAM, or that RAM is just a proxy measure of other factors (high end, versus low-end devices, device age, networks those devices are run on…etc.), doesn’t really matter at the end of the day. If it’s a good proxy that the experience is likely poorer for those users, then we can use that as a signal to optimize our site for them.

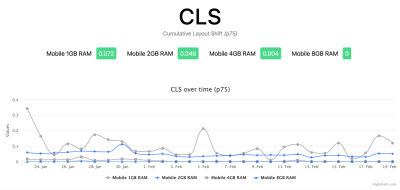

Cumulative Layout Shift (CLS) has some correlation, but even at the lowest memory is still showing green:

This is perhaps not so surprising since CLS can’t really be countered by the power of devices or networks. If a shift is going to happen the browser will notice — even if it happens so fast, that the user barely noticed.

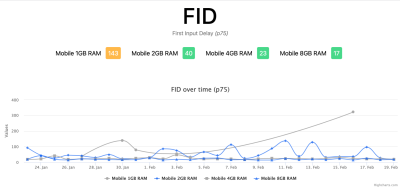

Interestingly, there’s much less correlation for First Input Delay (FID). Note also that FID is often not measured, so can result in breaks in the chart when there are few users in that category — as shown by the 1GB devices series which has few data points.

To be honest, I would have expected Device Memory to have a much bigger impact on FID (whether directly, or indirectly for the reasons as discussed in the LCP section above), and again perhaps reflects that this metric isn’t actually that difficult to pass for many sites, something the Chrome team is well aware of and are working on.

For privacy reasons, device memory is basically only reported as one of a capped, fixed set of floating-point numbers: 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, so even if you have 32 GB of RAM that will be reported as 8. But again, that lack of precision is fine as we’re probably only interested in devices with 2 GB of RAM or less, based on the above stats — though best advice would be to measure your own web visitors and based your information on that. I just hope over time, as technology advances, we’re not put into a similar situation as ECT where everything migrates to the top category, making the signal less useful. On the plus side, this should be easier to change just by increasing the upper capping amount.

Measure Your Users

The last section, on correlating Device Memory to Core Web Vitals, brings about an important topic: do not just take for granted that any of these options will prove useful for your site. Instead, measure your user population to see which of these options will be useful for your users.

This could be as simple as logging the values for these options in a Google Analytics Custom Dimension. That’s what we did here at Smashing for a number of them, and how we were able to create the graphs above to see the correlation as we were then able to slice and dice these measures against other data in Google Analytics (including the Core Web Vitals, we already logged in Google Analytics using the web-vitals library).

Alternatively, if you already use one of the many RUM solutions out there some, or all of these may already be being measured and you may already have the data to help start to make decisions as to whether to use these options or not. And if your RUM library of choice is not tracking these metrics, then maybe suggest that they do to benefit you and their other users.

Conclusion

I hope this article will convince you to consider these options for your own sites. Many of these options are easy to use if you know about them and can make a real difference to the users struggling the most. They also are not just for complicated web applications but can be used even on static article websites.

I’ve already mentioned that this site, smashingmagazine.com makes use of the Save Data API to avoid loading web fonts. Additionally, it uses the instant.page library to prefetch articles on mouse hover — except for slow ECTs or when a user has specified the Save Data option.

The Web Almanac (another site I work on), is another seemingly simple article website, where each chapter makes use of lots of graphs and other figures. These are initially loaded as lazy-loaded images and then upgraded to Google Sheet embeds, which have a handy hover effect to see the data points. The Google Sheet embeds are actually a little slow and resource-intensive, so this upgrade only happens for users that are likely to benefit from it: those on Desktop viewport widths, when Save Data is not turned off, when we’re on a fast connection using ECT, and when a high-resolution canvas is supported (not covered in this article, but old iPads did not support this but claimed to).

I encourage you to consider what parts of your website you should consider limiting to some users. Let us know in the comments how you’re using them.

Further Reading

- Time To First Byte: Beyond Server Response Time

- Creating An Effective Multistep Form For Better User Experience

- Time To First Byte: Beyond Server Response Time

- Why Optimizing Your Lighthouse Score Is Not Enough For A Fast Website

Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

Register Free Now

Register Free Now