Resolving Conflicts Between Designers And Engineers

In software development, UX designers and software engineers can get locked in verbal combat, which feels like a chess game of debate and wordplay. I’ve been there too many times and have the battle scars to prove it. If there has been anything I’ve learned from conflicts in the software development process, it’s that it’s not exclusively a cultural phenomenon, and obviously, it’s not productive.

The people involved in the conflicts generally react to a negative state of the world that no one wishes to be in. Sometimes it says more about a particular culture than us as individuals. Regardless of the reason, it’s not a good state for the organization or company to be in and will rob you of productivity, team cohesion, and focus on delivering customer value. Every company and department has its own challenges. In this article, we will go over some areas where you might find the challenges manifesting, what some of the contributing factors are, and strategies to work through the challenges.

I used to see the conflict between design and engineering in the software development process as annoying and an impediment to software design. When I began to see patterns in people and organizations involved in the conflicts mentioned above, I started to lean into the conflicts and see them more as an opportunity. I want to highlight some common contributing factors to design and engineering conflicts and lay out some strategies to work through them.

“

If the two sides (design and engineering) don’t come together in perfect harmony, it could result in a functional feature that customers don’t enjoy or a good experience that’s not efficient and/or expensive to build. It’s not an either-or but an “and.” The design and the tech have to come together in harmony to balance the feasibility with aspects of a delightful experience.

I have found that, often, it’s easier for an engineer to see the aspects of a good user experience than for a designer to understand the technical aspects of how something functions, let alone how feasible it is. Regardless, the two sides work best when both lower their guards and reach across the aisle. Only then are your teams truly committed to delivering a great customer experience.

Assessing The Chasms

There can be several contributors to the aforementioned dissension. From an organizational structure standpoint, contributors to the chasm could be boiled down to the following categories: culture, teams, roles, and individuals.

A review of the literature in saylor.org’s course lays these categories out in a bit more detail, and they note that “sometimes the structure of the organization itself can directly lead to conflict” whether that be based on the organizational structure or the authority provided within the structure.

I’ve seen these categories manifested in several ways. You may be able to relate to some of them. Let’s discuss them below.

Culture

People do what they get rewarded for. If your organization incentivizes teams based on productivity, they will get good at cranking out widgets. Even if those widgets fall short of the customer expectations, the teams will become good at delivering what you asked for. Their focus becomes output over outcomes. This can cause teams to cut corners and produce “good-enough” solutions that miss the mark once released to customers. This is largely driven by the culture within the organization and can permeate the management hierarchy.

Teams

Similar to what I mentioned regarding culture, a team, while aligned with the larger culture, typically has a team sub-culture. Sometimes a team culture can be seemingly at odds with the corporate culture. For example, a corporate culture that is collaborative and open can have teams that are hyper-focused on metrics and productivity that misconstrue the intent of the culture to meet productivity metrics. This is generally done to reduce uncertainty. I’ve worked with teams that became so hyper-focused on themselves that sizing a single user story practically took up an entire meeting.

Roles

Staying in our lanes as designers and engineers. Personally, I couldn’t be more opposed to people staying in their lanes. I recognize that designers and engineers fulfill specific business needs, but we should be a unified body when it comes down to delivering outcomes. Engineers should have opinions on design, and designers should have opinions on the applied technical solution. The cross-pollination of views should support one another, which almost always leads to a better outcome.

Individuals

I can be a contributor or a hindrance. I can become so focused on myself and my desires that I close myself off to others’ views. Rather than focusing on the outcome and the team, my views are forced on others, including the customer. I have seen this causes engineers to be entirely focused on output, “Just tell me what you want from me,” rather than collaborating on the outcome.

United We Stand Or Divided We Fall

Let me provide a few examples from my experience. I worked at one company where I tried several experiments to work more effectively with engineering. At a certain point, a prevailing schism was entrenched and a rather strong engineering-focused culture of “let us build it, get out of the way, and we’ll let you know what we need.” This tension had created an “us vs. them” mentality.

For this same company, I was brainstorming with a team for an upcoming project. As we started to get into sketching, I was met with blank stares followed by a litany of technical constraints. It was awkward, to say the least. Reflecting on it, I don’t think it went well because there wasn’t Product Owner buy-in, nor the proper context was set. I realized from that experience that when we are entrenched in a particular culture/team mindset focused on output for an extended period of time, it can be poisonous and entrench not only our behavior but also our mindset.

Last but not least, while working at a different company, I noticed a middle management cultural problem. The senior leadership spoke about collaboration, great design, and high quality. The agile teams executing on work agreed with this philosophy and were trying to work towards the leadership vision. However, middle management was making decisions that conflicted with senior leadership. The engineering manager would tell engineers to build things that completely excluded design. When designers tried to engage in the process, the engineers were just following orders. There were engineering building and shipping things with little to no Product Management or UX Design input, which showed in the product.

“

It is wise to give the organization and teams the benefit of the doubt. Too often, we’re all just caught in the middle of what appears to be dysfunction. That dysfunction can be an opportunity for change if we learn to navigate the distraction that leads to conflicts.

Distractions

Several studies have dug into this problem space of conflicts with teams, specifically UX designers and software engineers. A 2002 study by Dejana Tomasevic and Tea Pavicevic found that “tasks conflicts are the most common type of conflict. A 2019 study by Marissa Wilson also found that “100% of conflicts reported were task conflicts”.

After being in the trenches for a while, I’m not surprised by these studies, so I’d like to add some color to the study findings directly from the trenches. From my experience, most of the barriers to engineering and design collaboration are simply distractions. Although cultural issues can be barriers to collaboration, if people really want to bring about a positive change, they will find a way.

Let’s review some distractions that you’ll likely need to overcome:

- Timing

Designers generally build up ideas (induction) while engineers break them down (deduction) to chunk out building the solution. While there is time to build up ideas and time to break down work, getting the timing right for either of these is important to avoid conflicts. Too often, we’re trying to build up ideas, and our partners are trying to break down the work. - Miscommunications

Designers and engineers have different skill sets and backgrounds. As a result, both groups come from different perspectives, speak different languages, and use different terms. This can lead to tremendous frustration, as Ari Joury points out in his article on designer and developer clashes. - Mis-alignments

If you don’t have the same frame of reference, you will have disagreements. It might be impossible to share every detail at every moment with everyone on the team, but there must be a shared understanding of the problem and the value the team is targeting. Misalignments can cause teams to pull in different directions. - Role factions

Sometimes teams get too focused on who’s responsible/owns what part of the solution. In a truly collaborative environment, the team owns the solution they’re working toward. Designers should get comfortable leaning into the engineering space, even if it’s to learn more about it. Same for engineers, lean into the design space and learn. - Metrics

Metrics help teams to be more focused on the outcome. They also help us be more incremental in our approach. You definitely want a healthy balance here because metrics on value delivery vs. metrics on team productivity can sometimes feel at odds. This can lead teams to focus on getting all the details right, which robs time away from delivering an outcome. Winston Churchill once said, “perfection is the enemy of progress.”

Though the list above is not exhaustive, there have been common themes in the various companies and teams I’ve worked with. The teams you work with within your company may be experiencing one or multiple of these distractions. Hopefully, not all of them! Regardless, designers and engineers will have conflicts if they work together. It’s our job as business partners to lean into them and work through them for teams to be successful.

Striving For Unity

I think it’s crucial to understand that trust has to be the cornerstone of any team unity. In an article by Built In in 2021, they provide a variety of examples for uniting teams. In it, Jillian Priese, Engineering Manager at Granular tells us that for her teams, “When trust is present, it makes all the difference in the world.” And that without trust, it’s “easy for engineers and designers to question one another’s motivations and abilities.” Whatever the barrier, we must employ strategies to close the gaps and bring unity to the team.

Here are some tips that I’ve found to be effective:

- Discover together.

While the design team is in the discovery phase of a project, make a point to include the engineers. In the research stage, they can be observers while hearing from actual users of their code. Don’t forget to include them in the ideation process as well. Give them room to fall in love with the problem space. As you discover, iterate, and refine, pull in engineers to get their input, particularly in areas where you want special interactions to take place. They can help you balance the approach to provide more value and be more feasible. - Be curious.

Try not to assume too much and be prepared to learn. Designers have a lot to learn from engineers, and engineers can learn a lot from designers. Cross-pollination of skills strengthens teams. You don’t have to be a designer or engineer, but you should spend some time learning a little about your partner’s role and their work. Exercise empathy and keep each other honest. - Speak their language.

As Ari Joury notes in his article, designers and engineers speak different languages. Designers and engineers sometimes assume they’re speaking the same language and using the same terms only to find that when the wires get crossed, they are talking about different things. Sometimes you will learn to slow down for clarity and shared understanding. Engineers need to be willing to patiently translate foreign technology to designers. Designers need to be ready to patiently sketch and use visuals to translate concepts to engineers sometimes. - Be together.

I literally mean that you sit with each other when you can. As a designer, I have learned a lot from sitting with or in near proximity to engineers about their work, each of them individually, about myself, and the need to modify my work behavior to be a better partner. If you happen to be remote, make a team commitment to be available whenever needed, and be sure you follow through on that commitment to help build trust.

It’s really powerful and rewarding when engineers are more aligned with UX designers because they can elevate good designs to be great designs when they’re fully engaged. I like to believe that engineers breathe life into UX designs through the power of technology.

Practical Examples

As noted above, no company is the same, and different tactics should be used depending on your team’s challenges. Here are some practical examples of how I have put the tips above into practice.

Growing By Learning

At one organization, I came in as the lone designer being dropped into an existing team. It was awkward because the culture had generally been tech-centric. I was the outsider and struggled to make headway. Over time, I realized that the team was open to more design collaboration but was a bit new to working with a designer. The team was in another country, so I petitioned to spend a few days working with them.

Part of my plan was to focus on our epic, which has a lot of frontend work; the other part of applying some design exercises. Since the team was new to design thinking, we did a lateral thinking exercise and UI pattern workshop. After that, things began to gel with us. The team became more user aware and empathetic, and the team started to come to me with UI defects and great ideas for solutions. I enjoyed working with that team.

Make Yourself Available

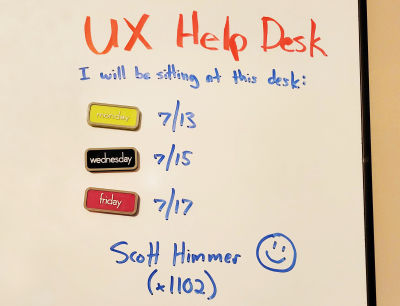

At another smaller organization, the UX team was positioned with the Product Management (PM) department. The PM and Engineering departments were located on separate floors in the same building. It didn’t take long to realize that the barriers to collaboration while manifesting in several ways, were rooted in physical separation.

To start working to resolve this, I set up shop in the engineering space a few times per week. A sort of “UX Help Deck,” if you will. At first, I think they thought it was weird, but eventually, people began to open up. It facilitated many opportunities to better understand the team’s needs, educate them on the users’ needs, learn about their tech stack, and find in-roads with Product Owners and Engineering Managers. Fortunately, much of the engineering team appreciated it. So, we built great relationships and made a lot of progress in a short amount of time.

Playing To Their Tune

At a much larger organization, I worked against a heavily entrenched engineering-centric culture. I made quite a few mistakes in that environment, such as not seeking more clarity on the authority of roles for the project, not pursuing more clarity in the project direction and priorities, and pushing back more against unreasonable hot-headed stakeholders.

I gained a lot of patience working with architects that had little experience working with UX designers. We were speaking different languages at different levels about different needs. They had a ton of domain knowledge from years of experience. So, they would pull these obscure edge cases out of thin air in conversations as a sort of trump card to any reasonable design recommendation. It was frustrating and humbling. To them, UX was all about “looking pretty” (the visceral aspects of the user interface). Sigh.

From my end, they saw UX as the lipstick they could just apply to the pigs they wanted to build. The in-road there was playing to their mindset. The architects fundamentally wanted to build a system that was robust, scalable, and easy to maintain quickly. The system being user-centered was the least important in their mind, and even that was generally boiled down to “looking nice,” which is not user-centered.

However, I believed we could build user-centered solutions and teach them along the way, but I had to think more modular and scalable. We needed to establish a frontend framework quickly and lay down some foundational guidelines we could build upon. We used that as building blocks that engineering could buy into. That helped them see UX as an ally to their goals rather than an adversary. We created a design system that helped us focus on user needs yet efficiently design at scale. While we got buy-in pretty quickly with engineers, we eventually began to see traction with the architects as the slow, grueling process slugged on.

Conclusion

Finding the impediments that are preventing the unification of the clan is important. It’s essential for your organization, your customers, and your sanity. It does entail effort but is well worth it. Experiment with your teams to find what works for them. The same strategy might not work for every team. When you meet resistance, don’t pull away, but lean into it and be patient.

As a reminder of the things we covered:

- Assess the level at which you’re finding the biggest chasms;

- Identify the distractions you’re seeing in your teams and what might be contributing to them;

- Take action and experiment with different tactics to establish unity.

“

You may not make friends at first, but you will get respect. You may find that thirty percent of the people are on board with you. Another thirty percent are interested but not yet sold. The remaining percent of nay-sayers who want to continue with the status quo will eventually come along as the rest of the clan unites around them. Fight the good fight, my friends, and unite the clans!

Further Reading

- “From Chaos To System In Design Teams,” Javier Cuello

- “Bridging The Gap Between Designers And Developers,” Matthew Talebi

- “Improving Your Team’s Communication In The Age Of Remote Work,” Obed Parlapiano

- “Better Documentation And Team Communication With Product Design Docs,” Ismael González

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

Register for free to attend Axe-con

Register for free to attend Axe-con Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers Register Free Now

Register Free Now